About Alfred Baeumler’s Nietzsche

Miguel Serrano collected works https://archive.org/details/miguel-serrano_202312

About Alfred Baeumler’s Nietzsche

Juan Sebastián Gómez-Jeria (PhD)1*

1Glowing Neurons Group, CP 8270745, Santiago, Chile

DOI: 10.36348/jaep.2023.v07i08.006 | Received: 14.07.2023 | Accepted: 20.08.2023 | Published: 23.08.2023

*Corresponding author: Juan Sebastián Gómez-Jeria (PhD) Glowing Neurons Group, CP 8270745, Santiago, Chile

Abstract

Two texts are presented here. The first is by Gerhard Lehmann who talks about the philosophical and political activity of Alfred Baeumler. The second is the first English version of ‘Nietzsche and National Socialism’ by Alfred Bæumler, Philosopher, Full Professor at the University of Berlin, Director of the Institute of Political Pedagogy.

Keywords: Friedrich Nietzsche, Alfred Baeumler, Gerhard Lehmann, NSDAP, Alfred Rosenberg.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s): This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium for non-commercial use provided the original author and source are credited.

INTRODUCTION

Alfred Baeumler (19-11-1887 - 19-3-1968), was an Austrian-born philosopher, pedagogue, and prominent National Socialist ideologue. From 1924 he taught at the Technische Universität Dresden, at first as a Privatdozent. Baeumler was appointed associate professor in 1928 and full professor a year later. Member of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP, or 'Nazi' as Dr. Goebbels used to say). From 1933 he taught philosophy and political education at the University of Berlin as director of the Institute for Political Pedagogy. After 1945, Baeumler was interned for three years in concentration camps in Hammelburg and Ludwigsburg. He was one of the few Nazi professors who did not return to a university post because he had not yielded an iota in his political positions.

It was Baeumler who first introduced Nietzsche as a philosopher in the late 1920s. His analysis presents Nietzsche as a philosopher of National Socialism. Baeumler himself says this: 'It was I who first introduced into the critical literature on Nietzsche these two theses: I. Nietzsche is a philosopher; II. Nietzsche's theoretical universe is unitary’. These two theses later gave rise to several books by other authors. It is enough to review the texts and their publication dates to realize this. But after 1945 it was decided to de- Nazify Nietzsche (the funny things about all this is that he never was a nazi and remember that during the Third Reich the judgments on Nietzsche were not unanimous). Baeumler is then denied having been the first to see him as a philosopher since he connected part

of Nietzsche's thought with National Socialism. This oblivion occurred only for ideological reasons and in all possible areas. Above all, an attempt was made to create and present a Nietzsche ‘washed with detergent’. Others, such as Montinari accuse of forgery the one who first discovered Nietzsche as a philosopher. As Marianne Baeumler said, 'we cannot ignore the fact that Baeumler 'Germanized' Nietzsche (deducing it, albeit univocally, from Nietzsche's own writings), just as we cannot deny that he understood Nietzsche's anti- Christianity as a significant historical event. Both aspects are constitutive of the general historical- philosophical vision developed by Baeumler during the time of National Socialism, and therefore can only be analyzed and judged through an objective approach. Baeumler prepared himself for this task by writing his unpublished writings, and therefore his thought can only be evaluated by the criterion of the analytical and philological method. But Montinari prefers to descend to the level of political defamation (using the ad hominem fallacy) [1]. I suggest to read on this subject something written at the end of volume IV of the Collected Works of Nietzsche (in Spanish) [2]. It is a text full of disqualifying adjectives that indicate the twisted path that the intriguer wants the reader to follow. And an aside of mine that I will expand in another text: it is enough to understand, even mediocrely, what the 'superman' of Nietzsche is, to be clear that he could not have been a National Socialist, nor a worshipper of the Golden Calf or anything that resembles something existing even today.

Another level of lack of understanding of the work of various philosophers was created out by the

Citation: Juan Sebastián Gómez-Jeria (2023). About Alfred Baeumler’s Nietzsche. J Adv Educ Philos, 7(8): 283-295. 283

physicist Mario Bunge ('they say that Heidegger was a Nazi philosopher. No, it is not true, he was not a philosopher, he was a charlatan, a servile of Hitler', '... nor a nihilistic philosophy, like Nietzsche's, which denies everything, everything good: it denies that benevolence, cooperation, mutual aid exists, it is a philosophy of war, it is a philosophy of aggression', 'Many of those who call themselves leftists rant against science and are anti-scientists without reason. They spread the stupidities of Heidegger, of Habermas, of Nietzsche, who has been refloated when we had sunk him forever in the darkness of Nazism', etc. All an excess of verbiage with touches of positivism, scientism, and lack of information; together with zero arguments since the works of all the just mentioned cannot be reduced to set theory or to a couple of 'logical statements'). Political defamation is not an argument, let alone the use of the Reductio ad Hitlerum. And for the record, I have used some of Bunge's excellent works in my writings and in some lectures.

After reading the six volumes of Nietzsche's correspondence [3- 8], the four volumes of his works [2], [ 9- 11] and the four volumes of his posthumous fragments [12- 15], to the most I dare to call myself a Nietzsche enthusiast. Of exegete, nothing. The only thing I can say is that, like many artists and philosophers, Friedrich went through several stages (his personal journey). That allows many ideologies or groups of ideas from the right, left, above, below, front, and back, to declare that they are 'Nietzschean'. Recall that Hitler was only 11 years old when Nietzsche passed away. The link that Baeumler makes between Nietzsche and National Socialism goes through the experience of The Great War (1914-1918). That experience was horrendous (the trenches and chemical warfare, initiated by the German jew Fritz Haber, who was indicted as a war criminal for violating the Hague Convention and for his responsibility as the ‘father of chemical warfare’). Two texts are presented here. The first is by Gerhard Lehmann who talks about the philosophical and political activity of Alfred Baeumler. The second is by Baeumler himself and deals with

Nietzsche. We hope the reader will enjoy them.

About Prof. Dr. Gerhard Lehmann

Gerhard Lehmann was a German philosopher and important researcher of Kant committed to National Socialism. He was born in Munich, Germany, in 1888. He studied philosophy, psychology, and logic at the universities of Berlin and Freiburg. In 1913 he obtained his doctorate under the supervision of Edmund Husserl with a thesis on the foundations of logic. After graduation, Lehmann worked as a private tutor in Heidelberg. In 1919 he became Privatdozent of the University of Freiburg. Later, in 1925, he was appointed associate professor and finally full professor in 1930. He served as full professor of philosophy in Freiburg until 1956, when he moved to the University of Munich. He retired in 1956 but continued his

phenomenological research. Lehmann stood out for his analysis of the intentionality of consciousness and for his contributions in epistemology, ethics, and metaphysics from a phenomenological approach. His main influences were Husserl, Heidegger and Scheler. He published important works such as 'Die Frage nach dem Sein' (1934) and 'Erkenntnis und Wirklichkeit' (1940). In his review 'Die deutsche Philosophie der Gegenwart' (Stuttgart 1943), he described Alfred Rosenberg's 'The Myth of the 20th Century' as a 'work which far transcends the field of contemporary philosophy and contemporary history'. He died in Munich in 1977, aged 89. He left an important legacy in the development of phenomenology in Germany during the first half of the twentieth century.

‘Alfred Baeumler’ By Prof. Dr. Gerhard Lehmann [16].

Alfred Baeumler is one of the leading political thinkers of our time as a philosopher of history, pedagogue, and epistemologist. The purpose of presenting 'politics', as he said in his inaugural lecture in Berlin in 1933, is not to politicize from the podium or call for politicization, but to draw an image of man that corresponds to reality. ‘I will put in place of the image of the New Humanism of man the true image of the political man, I will redefine the relationship between theory and practice, I will describe the orders of life in which we really live, I will communicate my ideas, but I will not get involved in politics’. Seven years later, in a speech at the Hans Schemm House in Halle, Baeumler once again emphasized this anthropological approach to political philosophy: 'We must begin with ourselves as we are. Without worrying about what kind of 'being' this is, we begin with the human being, not with reason, not with the rational soul, not with a higher being called spirit, but also not only with nature, with the mere living being, but with the real human being as we know him from our experience. In adherence to this approach lies the philosophical’. This is Baeumler's realism, his anthropologism, his departure from 'imageless' (abstract) idealism.

Baeumler was born in 1887 in Neustadt an der Tafelfichte (Sudetenland, Germany). He studied in Munich and obtained his doctorate here in 1914 with a thesis on the 'Problem of General Validity in Kant's Aesthetics'. After participating in World War I, he was enabled in Dresden in 1924 on the basis of a work on Kant's Critique of Judgment (1923), which would continue in a work on the 'Problem of Irrationality in Critical Philosophy'. He became an associate professor at the Technical University of Dresden in 1928 and a full professor of philosophy in 1929. The revolution brought him to Berlin in 1933: a chair of political education had been established for him, in connection with a political-pedagogical institute, of which he became director. He had to face a large number of tasks: academic, organizational, and official party officials. Since 1936 he has published the journal

'Weltanschauung und Schule' [Worldview and School]. Another educational journal, 'Internationale Zeitschrift für Erziehung' [International Journal of Education], has been published under his direction since 1935.

Baeumler's thought was and is decisively determined by Kant. Baeumler himself confesses that he owes his philosophical training to the third Critique, the 'book of destiny' (as opposed to the Critique of Pure Reason as the 'basic book') of Criticism. Even then, it is an 'image' of the man he wishes to draw: the classical character. The classical, understood as lifestyle and humanity, was embodied by Goethe, and thought by Kant. 'The Critique of Judgment and Goethe, that is thought and its existential expression'. It is clear that this approach, if it was to be more than an ingenious vision, required a new interpretation of the Critique of Judgment, indeed, of Criticism in general: an interpretation from the point of view of Kant's concept of totality and individuality. 'If the unification of a critique of taste with an epistemology of biology... In a single book it is more than the eccentricity of an old man..., then the real meaning of the last criticism must be sought neither in aesthetics nor in the doctrine of the organic, but in that generic concept which unites the objects of the aesthetic and teleological power of judgment under itself. This generic term is individuality’. Thus, Baeumler's account, although initially dealing with the history and prehistory of the Critique of Judgment, ends in the systematic.

But is not this 'classical character' precisely the image of the man that Baeumler then wants to dethrone and replace with the 'true image of the political man'? Has he not himself made the turn he describes, the passage from a past apolitical order of life to the present? Two years after taking office in Berlin, Baeumler makes an analysis of the image of the man of the New Humanism in a speech on the centenary of Wilhelm von Humboldt's death, culminating in the assertion that this 'non-political' image is also a 'political' image, that is, political for the time in which it was created. It is no longer suitable for our time, whose social structure is different. Humboldt's concept of 'education', through the combination of the concept of power (Leibniz) and the concept of individuality (Kant), a document of the 'classical' character, fulfilled a political mission: the nobility could no longer provide the next generation of political leaders in the era of reforms; the bourgeoisie was ascending mightily. ‘In this situation, where all forces were striving to form a new political being, everything depended on finding a base on which those who felt in themselves the vocation towards a higher career beyond economic life could unite and educate themselves’. If Humboldt had created a scientific university of applied sciences instead of the neo-humanist 'university', 'then precisely the most important political effect could not have occurred'.

This immediately reveals a fundamental feature of Baeumler's essence, his ability to think in historically concrete ways. The way in which it appropriates the Kantian seculum of nineteenth-century philosophy in its own development is equally characteristic: the introduction to the book on Kant concludes with a reference to Hegel ('the presentation of the Critique of Judgment will lead, according to the content of the concepts, directly to Hegel's philosophy'), first dealing with Hegel, again from an aesthetic point of view; then with Kierkegaard, then with Bachofen, then with Nietzsche. It is not just the external stations of your research; it is not only fruitful encounters that ignite his philosophical reflection; at the same time, and this is characteristic, it is the flow of history that fertilizes contemporary thought. With a sure instinct, Baeumler closes himself to everything that does not carry this 'indicator of the present'; and if the beginning of history for him is not consciousness or spirit, but will or force, this is not yet a systematic hypothesis, for example, in the sense of 'irrationalism' which he has ceased to describe, but a simple experience of historical effectiveness. But there is more to this line of development: the real turn from idealism to realism, which is Baeumler's most important systematic decision and determines his thinking. The introduction he wrote for a selection of Hegel's writings on the philosophy of society (Part I: Philosophy of Spirit and Philosophy of Law, 1927) is precisely in line with this advance.

As it is said here, just as Hegel underestimated egoism in the practical realm, he also underestimated the concept of law in the theoretical realm. Moreover, it is said with Kierkegaard accents, that Hegel saw the struggle of the atoms of the will, but he did not take that struggle seriously. He didn't take 'the particular, the accidental and the natural seriously enough'. 'Inwardly', which is also very characteristic of Baeumler's way of expressing himself, nature is completely eliminated in Hegel: true subjectivity is not recognized at all in his problematic. Despite all the dialectics, Hegel's system remains dualistic like Fichte's: it is a 'two-point' system. So Hegel, the metaphysician, knows no real development either; everything happens at the same time: 'the mood of Hegel's metaphysics does not express becoming, but being’. The meaning of what Baeumler calls reality will be discussed later.

In the first place, two other points of Baeumler's philosophical-historical development should be highlighted, because they are outstanding moments of that 'existential' understanding that characterizes his historical works: his 'Bachofenbild' and his 'Nietzschebild'. He dealt with both thinkers on several occasions. In a smaller work (Bachofen und Nietzsche, 1929) he contrasted them vividly: the symbolist and the psychologist, Bachofen, the serene observer of antiquity, the bourgeois who at the same time embodies the strongest 'anti-bourgeois force' in the nineteenth century. Nietzsche, the fighter who recognizes his

agonal impulse in the 'heroic-true' existence of antiquity, who does not want to contemplate antiquity but to live it, enemy and despiser of 'bourgeois security', but whose 'audacity as a psychologist' was only possible 'against the background of the bourgeois system to which he himself still belonged as a demonstrator' (only later did he recognize the essentially instrumental character of Nietzsche's 'psychology': Nietzsche's psychology is not a decomposing subjectivism, but a means, a tool of struggle).

Two new editions of this late romantic, still almost unknown at the beginning of the century, are significant for Bachofen's research: that of Bernoulli and that of Manfred Schroeter. Ludwig Klages was the initiator of the first edition; the second edition resulted from Schroeter's collaboration with Baeumler. (The 'Handbuch der Philosophie', of great magnitude, 1926 onwards, in which several renowned researchers and philosophers participated, and which, following completely in Baeumler's sense, aims to prepare 'a thought that is not individualistic or arbitrary, but is driven by historical needs', is also the fruit of this working group). Baeumler has written an introduction, of more than two hundred and fifty pages, to Schroeter's edition, entitled: 'Der Mythos von Orient und Okzident: Bachofen, the mythologist of Romanticism'. In this introduction, he offers an interpretation of Bachofen that differs markedly from that of Klages. However, it also reveals a relationship with Alfred Rosenberg's concept of myth, which is important for understanding the formation of the ideas of National Socialism.

Bachofen should be understood as a philosopher of history, not as a 'timeless symbolist'. Bachofen, according to Baeumler against Klages, and a Swiss work by G. Schmidt, published three years after Baeumler's 'Introduction', in which all the passages are carefully examined, proves that he is right, 'interpreted by an anti-historical and anti- Christian spirit, he is no longer Bachofen'. But he is a philosopher of history insofar as he wants to write 'human history', human history not as universal history, but as history 'under the aspect of the relationship between the sexes'. If Bachofen starts from maternal law, this legal term is not essential, and may even be misleading for what he seeks and achieves: the exploration of the 'experiential pre- world' of history. It is equally wrong to interpret the concept of maternal right as a glorification of the feminine principle par excellence: 'The deepest starting point of 'maternal law' is not the abstraction of the mother in her relationship, so to speak, a posteriori with the children of her womb, but the original relationship of mother and child. Bachofen can only be understood as the mother's son; but also only as the mother's son.' With this, the accents of Klages' (idealist) interpretation shift completely: 'The alternative of the idealist, the question of the priority of day or night, is meaningless to Bachofen. Day is born of night, just as the child is born of the mother's womb’. And from here, the

meaning of the fundamental thesis, somewhat hidden in the book, immediately emerges that the mythical and the revolutionary are interdependent. ‘The man who wishes to understand myths must have a penetrating sense of the power of the past, just as the man who wishes to understand a revolution and revolutionaries must have the strongest consciousness of the future’. Just as the future belongs to the past, so the revolutionary belongs to the mythical.

The myth, however, is rooted in the People, not in the individual: the mythical thought of Heidelberg Romanticism, to which Bachofen's philosophy of history refers, is at the same time a popular thought. It is the emergence of a new attitude to life, a vision of reality that was alien to the eighteenth century. The concept of the People in Heidelberg Romanticism, the stages of development of which are clearly delineated in Bachofen's introduction, is not idealistic like that of Herder, Hegel, or the Jena Romantics; it is 'naturalistic' in the sense that the People is understood as a second and higher nature, as physis in a sense that is not yet biologically or even physically objectified.

Baeumler's research on Nietzsche has already been mentioned. In addition to a 1931 monograph (‘Nietzsche als Philosoph und Politiker’), there is also an 'Introduction' that Baeumler wrote for an edition of Nietzsche that he edited himself (1930). Here the focus is entirely on Nietzsche's personality, while the other account is more concerned with the content of his teaching. The key to Nietzsche's personality is Dionysus, not a Greek god, but himself a hieroglyph behind which an experience hides. Dionysus, pseudonym of the Antichrist, the earliest formula for the will to power, is 'a symbol of the last and highest exaltation of life, where preservation is no longer applied, but waste'. Dionysus means that 'unity of pleasure and pain that the living being feels when it becomes victoriously destructive and creative at the highest moment of its existence'. But the Dionysian is not univocal; Dionysius has two faces: Dionysius philosophos has entered the music of Wagner, and this corrupts his figure; philosophy and music, the two forces in whose tension Nietzsche's life passes, come together in the 'impossible concept of the tragic-musical myth'.

To undo this impossible connection, to separate the philosophical from the musical, is the effort that Nietzsche undertakes. ‘When life goes astray, when it has joined a music hostile to life, then the will must become the defender of life’. But Baeumler delves even deeper: the musical line and the philosophical line are themselves only images of two 'lines' whose entanglement determines human destiny in general: the line of death and the line of life. 'How can music become the servant of philosophy’; how can death be made subordinate to life? This is Nietzsche's problem,

for which 'Zarathustra' (in contrast to 'Birth of Tragedy') then offers the 'existential Dionysian' solution.

So what is the real content of Nietzsche's 'Heraclitian' philosophy? The shortest formula for this is that of a heroic realism, developed theoretically 'as if from a transcendental aesthetics of the body'. It is precisely from here that the concept of the 'will to power' acquires its meaning: the will to power is not a subjective phenomenon, it is not an effort of will or an excitation of the will; Nietzsche has put an end to the earlier philosophy of consciousness. The will to power is something objective, the 'unity of power' (rather than the unity of consciousness), the order of well-being as a reality of life. With conscience also falls responsibility; if one makes this very clear, then an alternative heavily emphasized by Baeumler becomes understandable: 'Either the doctrine of eternal return or the doctrine of the will to power’. Both cannot be equally essential to Nietzsche; for one cancels out the other. One must decide from which point of view one wishes to interpret. The doctrine of eternal return is 'moral'. It is static and ultimately devalues the Heraclitian approach that has been justly validated by modern physics, as Baeumler attempts to demonstrate.

Baeumler's thought is not systematic in the explicit sense, that is, in the sense of a conceptual system that rests on itself. But his commentary on Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Bachofen, Klages, the way he interprets the history of philosophy contains an implicit system, which he himself occasionally clearly emphasizes. If these indications are followed, a rich problematic content opens up, especially with the inclusion of the aesthetic sciences, whose origin, history, and criticism Baeumler addresses monographically in his 'Aesthetics' in 1933. Aesthetics has the peculiarity that it is not ignited by the appearance of art, but by the appearance of beauty: the metaphysics of beauty and the theory of art are so divergent that the fundamental philosophical problem of 'being as form' is corrupted by the so- called 'aesthetics'. Plato and Plotinus absolutize beauty; The image becomes the appearance of the idea, and aesthetic subjectivism leads to the system of imageless idealism that leaves reality behind. Baeumler's struggle is directed at this 'system'. His efforts in Dionysius and Zarathustra, in the myth of Bachofen, in the concept of style in art ('the phenomenon of art cannot be derived from experiences and efforts of expression', he says in 'Aesthetics' 1933. 'Art can only arise from the will to perpetuate a content, and the expression of this will is style'), find their continuation in the fact that Baeumler was the first to undertake a philosophical evaluation of the pictorial content of National Socialism. Familiar with archaic imagery and what sociology used to study in a more positivist sense as 'collective ideas', he sets himself the task of interpreting the symbols of our time: symbol and word, image and concept are opposed; the word is eloquent, the symbol is silent, the word is

stripped of power, the symbol has power over us: 'For this is the peculiarity of the images of our soul, which demand our use’. The path of culture leads from symbol to word, certainly. But when the word becomes powerless, the culture unproductive, regeneration can only come from the deepest layer of wordless symbolism. The National Socialist revolution is under the sign of this regeneration. 'We are united in symbols; we are not yet united in words’. It would be a false romanticism to understand the symbols of our time only from feeling or experience; It would be reactionary to look for the right word for new content in the past. ‘We are not romantics, we follow the path to the word, and the path to the word is the path to classicism’. Baeumler also takes a stand against irrationalism and against hostility to the spirit of neo- romanticism. The philosopher has the duty to interpret the symbols towards the word: 'the most arduous task of the mind is none other than to interpret symbols'.

The work is difficult because it is a realization of reality. The symbol does not stand as a symbol of something subjective above reality but is concrete: it is the effective historical-political factor, it separates and unites, it is the embodiment of that 'real us' that is never found at the level of mere community of feelings.

What is reality? Since the turn of the century, modern physics has found itself in a fundamental crisis regarding the nature of causality, the absolute determination of the world, the position of the observer in relation to the object, the validity of claims about reality. Should this just be a separate matter from a 'discipline', or rather be the expression of a historical process that affects all of science and philosophy? Thus, Baeumler finds that the fundamental crisis of physics is closely related to the collapse of the 'humanist system' (where 'humanist' has a double meaning for Baeumler: a positive one, referring to 'height', a negative one, referring to the breadth or 'extent' of 'man'; the first meaning refers to the 'great form' of the classical character, while the latter refers to man's lack of structure 'in general'): this system was an ‘absoluteness system’ within which an absolute world corresponded to the absolute spirit. The meaning of the universal causal law is rooted in this claim of absolute knowledge; the equivalence of time phases, the principle of calculability of the future, absolute 'security' are the characteristics of a causally determined reality. And now the curious thing: by abandoning the absolute system of nature, which is based on 'repeatability', the 'recurrence of all the same', physics gains a greater closeness to reality. Today's physics is more 'realistic' than classical physics.

The same is true in the realm of the spirit. The humanist system of absoluteness, which was regarded as the system of the theoretical 'human being', contained the claim to an absolute position. Consciousness as the center of a neutral frame of reference, the free and self-

determining ego, the autonomous human being: all these ideal cases that fit with the ideal cases of classical physics! By abandoning this position of absolute objectivity and 'innocence' and realizing that the knower and the known 'are not separated by an infinite distance, but there is a finite distance between them, by affirming that only the whole man knows, the man who 'has' consciousness, is not 'held' by a 'pure' consciousness; are we again facing cheap relativism, or are we closer to reality?

It is a mistake of relativism to take the concept of truth lightly. 'Overcoming' relativism means nothing more than restoring the primacy of formal logic, and this is the point at which Baeumler's own 'logic' begins. However, it is mainly Hegel's speculative (dialectical) logic that decisively asserts the primacy of formal logic over Baeumler. Self- awareness, which is not a special 'mode of being' and does not 'contain' a special access to the Absolute (from 'within'), must be conceived as the point of reflection of a type of thinking that originates within the realm of our human frame of reference, a type of thinking that recognizes its limits and transcends them. Therefore, Baeumler's formal logic in its application to knowledge is a transcendental logic, but precisely in its application to the human being, not to a pure fictitious knowledge. Moreover, it is easy to see that absolutism and relativism are mutually dependent. If the absolute frame of reference, the absolute truth (idea) vanishes, then relativism as a worldview also vanishes. The traditional doctrine of ideas, which aims to justify reality and give it a 'meaning' that it has previously taken from it and transferred to another 'world': of values, of the spirit, is always pathetic, priestly doctrine of the two worlds becomes irrelevant when the idealist scheme of interpretation is unmasked. Dissecting reality in form and substance, destroying it in order to 'construct' it, forming its unstructured elements, torn from sight, 'into an image of the world' through later achievement, that is the ancient spiritualist approach, for which the actual, 'positive', requires transfiguration through values and meaning in order to be 'saved'.

On the other hand, if one chooses to recognize reality itself as the 'foundation and measure of all forms', not to subordinate it as a mere fact to a 'higher' reality, then philosophy becomes realistic. It becomes a 'philosophy of reality', which is modest, merely meaningful, 'indicative' and leaves behind the traditional opposition between positivism and idealism, as well as the opposition between relativism and absolutism. For a philosophy of reality like this, reality is neither 'realization' nor the place of realization of something unreal. The idea also takes on a different human-political meaning for them. 'The idea comes from reality itself; it is the image that reality produces of itself through the human being'. There is only one reality whose depth is inexhaustible, unfathomable. There is an original relationship with reality: to observe

the world and take from it the guiding principles of one's actions. There is a 'manifestation' of reality that does not presuppose the absolute distance of 'pure' consciousness from its objects, but is fundamentally practical, political. Here, things are not talked about irresponsibly. Rather, it responsibly shows the reality in which the speaker finds himself, his existential situation.

This situation is, in itself, political, that is, it embraces the human being as a personal unit in the community and in action for the community. Just as there are political actions only within the framework of a field of action, a system of action, our political existence is also a being situated in a real and fateful context through which we are connected as personal units with the past and the future, in a context of blood and race. Race is, therefore, a basic political- anthropological concept: it is anthropological because the racial determination of the human being is not an external and random determination, but a determination of essence; it is political because it is the center, the deep center of those 'actions and reactions' that are expressed in political action and determine our attitude.

Race is therefore also the basic concept of political pedagogy, the development of which coincides with Baeumler's Berlin years, and whose preconditions, problems, and tasks he seeks to clarify in several works of his last period (Männerbund und Wissenschaft 1934, Politik und Erziehung 1937, Bildung und Gemeinschaft 1942). Here, above all, emerge the basic lines of the implicit systematicity of his philosophical reflection. After all, 'political pedagogy' is not the 'application' of politics to education (and certainly not the application of philosophy to politics), but political activity itself, future-oriented and put at the service of shaping the future of our people.

Without going into details, we highlight only the moments that characterize the originality of Baeumler's approach: education as formative education and education of the body.

The two concrete forms of community: the family and the Männerbund (clan and followers) require two different forms of educational influence: family education and school education. Both here and there, it is the community that educates: the path from the family to the village and homeland is the destiny of each individual. Formative education itself is not school education in the above sense determined by the historical (neo-humanist) form of the German school, but its 'foundation' and political orientation. Formative education is education for and by the state, education in the 'house of men', as it was called in 1930, when the bourgeois way of life and its 'social' education system were still a reality to fight against. In the meantime, this education of the Männerbund has found its place in the

formations of the movement and its political security in the formations of the movement.

Physical education, however, is not only a prerequisite for formative education, but a basic condition of all 'education' as a development of individual skills and capacities. His approach arises from the relationship of the individual body to the whole body of the people: 'The body is a politician, that is the first conclusion we must draw from the idea of the people.' And like the body, character is also a politician; all physical education is primarily character education. The function and importance of the concept of race for realistic anthropology and pedagogy is to develop the predispositions of the body towards a certain type. On the other hand, the school is the educational institution linked to the means of instruction, instruction which, although directed to the head and intellect, is not imparted 'in the vacuum of reasoning’ but presupposes racial community as a principle of life.

Baeumler calls his philosophy a philosophy of reality, realism. But he has also spoken of a 'heroic

rationalism', and it is not superfluous to point this out at the end. This rationalism is heroic insofar as it does not presuppose reason as a fixed possession but dares to fight for the order of the spirit. From here, Baeumler's formula of the well-ordered reality of life acquires a fuller sound: life has followed a rhythmic order from the beginning, 'but only man is capable of representing the rhythm of the universe in self-created orders'. This 'representation' is really not just a representation of a reality 'in itself'. We ourselves live in the image, in archetypes, symbols, opinions and figures. That is our reality. But we do not live in it as disinterested observers, it only speaks to us when we act, we behave actively. If we dare to create a new order, not in the assurance of revealed truths, but as finite existences bound by blood, then we have realized the tendency of life that is effective in us, the 'will to power', which itself is an order. It is important to realize that Baeumler's philosophy of culture, unlike the philosophy of culture of idealism, did not 'abolish' natural philosophy, but complements it, because that is the characteristic of his 'rationalism'.

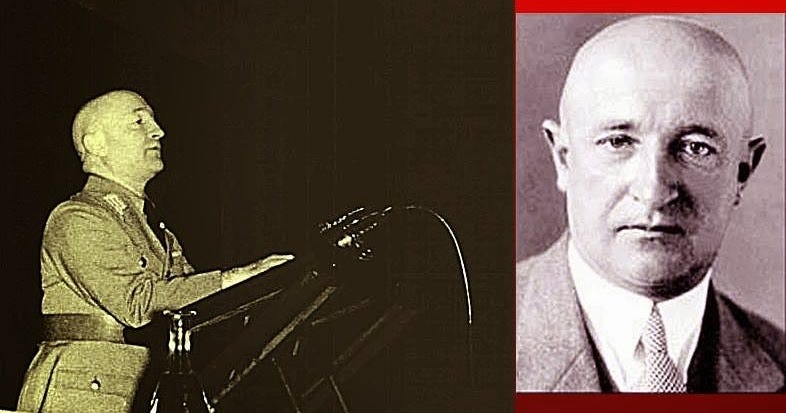

Figure 1: Adolf Hitler contemplating the bust of Nietzsche (left).Elizabeth Nietzsche with Adolf Hitler (right).

Figure 2: Adolf Hitler at Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche's funeral in 1935.

‘Nietzsche and National Socialism’ [17, 18] By Alfred Bæumler, Philosopher, Full Professor at the University of Berlin, Director of the Institute Of Political Pedagogy.

If the German revolution were simply an internal process within the German bourgeoisie, and if this revolution only involved a revision of already existing ideas, the topic 'Nietzsche and National Socialism' would have no relevant meaning.

But the 'y' in the title does not mean that in this case more or less close connections should be established between certain ideas of Nietzsche and certain ideas of National Socialism. Rather, it indicates a deeper connection between these two great entities. Nietzsche lived and thought like a loner, voluntarily departing from the German bourgeoisie, and fighting from his extreme position against the bourgeois condition as a whole. For its part, the National Socialist movement has a point of origin external to the bourgeois world. It is not born within the German bourgeoisie and its tradition but is the creation of a single man who has been deeply influenced by his political experience and the Great War.

National Socialism in its early days did not originate directly from Nietzsche. After World War I, no one thought to associate the new movement with Nietzsche. Back then, few really foreshadowed the true significance of the uprising of the German people that began on August 1, 1914. The event of the year 1933 opened the eyes of many, as it marks the beginning of a new world era. For us, the Great War produces an effect similar to that caused by the summits of the highest mountains: at first, they are only glimpsed in the distance.

But those who have before their eyes the Great War see Nietzsche and National Socialism simultaneously. Therefore, National Socialism was born of the fire and blood of the Great War, it turns backwards, towards the powerful community of our people dedicated to action and sacrifice, the great event of our history. Meanwhile, Nietzsche, from the perspective of his time, looked forward to this event. Among his contemporaries, he was the only one in Germany who foresaw the earth trembling and glimpsing the impending catastrophe.

With the assurance of a seer, he predicted nihilism, 'the most disturbing kind', and announced the state of confusion, lack of faith, the transvaluation of all values and the deterioration of all forms of life. In modern democracy, Nietzsche perceived the historical form of the end of the state, pointing with keen discernment as distinctive features of modern man all those tendencies that over the years have opposed Hitler's victory: in order, the neutrality of the intellectuals, the opportunism of the ruling class and its need for peace and security, the alienation of German

man towards nature and historical tasks. The lack of 'political guidance' during the First World War means nothing other than the disappearance of the German bourgeoisie from world history.

To his contemporaries, and even to his friends, Nietzsche was considered an eccentric, and even a madman, because he opposed everything hitherto considered valid. He was the critic, the denier, he didn't have any 'positive projects'! The same accusation has been constantly levelled at the National Socialist movement. In this accusation is expressed especially the distance that the great men of action, the precursors, those who propose the impossible, establish between themselves and those who only consider possible the existing. It was hard to believe that this Weimar Republic, this constitution, this bourgeois state structure, based on defeat and the unwillingness to overcome it, meant nothing, while showing itself in its effective reality through bans, dismissals, arrests, and beatings.

However, it was crucial that there was a man capable of nullifying and undoing all this. This man could not foresee what would happen in a year; In fact, no man of action could have predicted it. But he knew that all this was ripe for his decline, and that it was necessary to kick what was falling.

If we translate the position taken by Hitler towards the Weimar Republic into a solitary thinker of the nineteenth century, we get Nietzsche. In declaring war on the Weimar Republic, Hitler was also faced with a secular, and even millennial, evolution. At the same time that he undertook the critique of the formation, culture and politics of his century, Nietzsche also began his struggle against a millennial evolution. However, there were always those who saw in Hitler only the liquidator of the Weimar Republic, without understanding its true meaning.

Those who see only in Nietzsche the nineteenth-century liquidator also understand little. Both Hitler and Nietzsche are at decisive points in this important movement in our history, which we can call the 'Northern movement'. Along the political line of this movement are the monarchs by right of peace and war of the high Middle Ages, as well as the founding of Prussia, Bismarck, and Hitler. Along the spiritual- religious line of this Ghibelline movement are Germanic paganism, Eckhardt, Luther and Nietzsche.

Nietzsche and National Socialism go beyond the tradition of the German bourgeoisie, but what does this mean? In recent centuries, the great intellectual currents that have shaped the German bourgeoisie have been Pietism, Enlightenment and Romanticism. Pietism was the last authentically Reformed religious movement on Lutheran soil. It led people to withdraw within themselves from a hopeless political reality, wrapping

themselves in small private spheres. Pietism represented a religious individualism that enhanced the inclination towards psychological introspection and the study of biographies. Among the German Pietists, any non- political and hostile tendency to the state found its support and sustenance. In the same direction acted the radically different individualism of the Enlightenment. This individualism was neither religious nor sentimental, but rational and rationalistic; it turned out to be 'political' only in an anti-feudal sense, but incapable of building a lasting political system, although it paved the way for the capitalist economic system. In that case, man was represented as an autonomous individuality, detached from any original order and bond, as a fictitious subject responsible only to himself.

In opposition to this, the Romantics reconsidered the human being within their own historical-natural connections. The romantics opened our eyes again to power, to the past and the ancestors, to myth and the Volk (the people). The movement from Herder to Goerres, the Brothers Grimm, Eichendorff, Arnim and Savigny, is the only spiritual movement still alive. And it is the only one on which Nietzsche has fought.

It is no coincidence that romanticism remains the most unknown movement in our history. The German bourgeoisie did not accept it in its entirety, but adopted only what suited it in its salons. The real acceptance of romanticism was countered by the legend of Weimar classicism, created by the liberal- conservative bourgeoisie. Basically, this legend was built by merging illuminist elements with other constituents, such as romantic elements. Thus a broad political sphere was drawn that retrospectively embraced the entire era of the German spirit, within which Herder and Lessing, Schiller and Goethe, Humboldt and Hegel were inserted into a single perspective, assigning to this structure the function of configuring a 'cusp' of German history. But thus the most important thing of the time was ignored: the Ghibelline spirit that continued to live in it. Above all, it was not understood how this supposed 'classical' era did not have autonomous roots. It was composed of Enlightenment humanitarianism and the spirit and tenacity of exceptional men. There is no such thing as a 'Goethe's zeitgeist'; there is only one great loner named Goethe, along with an artistic synthesis called classicism. With the dissolution of the German bourgeoisie, this synthesis dissolves itself, revealing again the great loners: Lessing, the courageous opponent of orthodoxy; Herder, the noble precursor of the Romantics; and next to them, but far surpassing them, the great loners: Winckelmann, Goethe and Hölderlin. If we want to mention Nietzsche's predecessors, these are their names. All of them share an original and authentically German link with Greek antiquity, something absolutely unthinkable in other

peoples: a relationship that not only has a formal and aesthetic aspect but is nourished by Greek reality and religiosity.

When we define National Socialism as a Weltanschauung, we mean not only that the bourgeois parties have been annihilated, but that the very ideologies of those parties have been liquidated. Only those who act in bad faith come to affirm the need to deny what comes to us from the past. We, on the contrary, want to sustain the need to relate in a new way to the past, freed to contemplate the significance that has been hidden by bourgeois ideology; in short, the need to discover new possibilities of understanding the German essence. And it is at this point that Nietzsche preceded us. In the face of romanticism, we situate ourselves differently from Nietzsche. But what was his most personal and exclusive legacy, the total rejection of bourgeois ideology, has now become the possession of an entire generation.

Here I want to offer an example of what so- called German classicism has cost. If the German bourgeoisie had not gloated in the shadow of the classical ideal which it itself invented, then there would be the possibility that the fundamental concepts of romanticism would be transformed into political ideas. But the political character of the main concepts of romanticism has remained in an embryonic state. The German bourgeoisie has proved incapable of arriving at an overall vision. Bismarck's political leadership did not coincide with any ideal leadership of the bourgeoisie. As confirmation of this statement resonates a name: Treitschke. For all his great temperament, Treitschke failed to overcome the legend of Weimar classicism (which shrouds his political doctrine like a fog), nor could he explore the world of power with a free gaze.

Beyond the oppressive ideology of classicism lies Nietzsche's blunt assertion: 'God is dead.' This statement has been interpreted exclusively as a historical observation: faith in God has disappeared. God is no longer the power in our lives. Nietzsche no longer 'struggles' with the Christian God and is unaffected by his death. He is far from denying that there are still Christians, in fact, he bows to those few remaining Christians, finding in them a type of person far superior to that, for example, he can see among the artists of his time. In short, he is completely free from the resentment of the fighter who wants to break free. For Nietzsche, having knowledge of the death of the Christian God does not mean a fully developed 'idea', Nietzsche does not desire the death of the Christian God but a vision of the end of faith in the Christian God, the end of the Middle Ages in Europe.

'I have no knowledge by direct experience of real problems in the religious sphere. It completely escapes me the sense of why I should be a sinner...' We feel the hatred in the words with which Nietzsche

evokes his impressions of youth, recalling the pietistic- romantic Christianity and the hypocrisy of Naumburg. 'We, precisely we who were children in the swamp of the fifties, can only be pessimistic about the notion of 'German'; We can only be revolutionaries, we will never admit a state of affairs in which servile flattery prevails’.

Nietzsche criticizes Christianity as to its historical reality as he has known it. Before him, he perceives a disconcerting phenomenon: the more faith in God disappears, the more the image of a morality founded and existing by itself grows. This is a distinctive sign of the bourgeois condition: morality rather than religion. The content of this morality presumably corresponds to the content of what might be called Christian moral doctrine. The transition from one to the other is performed (at least in appearance) without fractures. 'It is believed that it can be fixed with a moralism without religious background; But this necessarily opens the way to nihilism’. ‘The Christian- moral God is no longer sustainable, and as a consequence we have 'atheism', as if no other kind of divinity could exist’. ‘Deep down, we have only surpassed the moral God’. ‘Christianity has become something very different from what its founder has done and desired’. ‘Precisely what is Christian in the ecclesiastical sense is from the beginning anti-Christian: simple facts and persons instead of symbols, mere stories instead of eternal facts, mere rites, formulas, and dogmas instead of a practice of life. Christian is the perfect indifference to dogmas, worship, priests, the Church, and theology’. ‘And it is an unparalleled prevarication that these configurations of decadence and forms such as the 'Christian Church' and the 'Christian faith' are designated by those sacred names. What has Christ denied? Everything that today is called Christian’. These words would even be subscribed by that great Protestant of the North, Kierkegaard!

However, it might be objected that the road leading to the Church was necessary. Nietzsche would answer thus: let us recognize that the path that goes from the Good News to the Church is the same path that enters history with its orders and laws, that is, the path that leads to politics. Nietzsche does not refute the Christian in his individuality: 'Christianity is possible as a form of absolutely private existence [...] A 'Christian state', a 'Christian policy', on the other hand, is an impudence, a lie, just like a Christian military command that ultimately regards the 'God of hosts' as a chief of staff’. 'Christianity is still possible at any moment [...] Christianity is a practice, not a doctrine of faith. It tells us how to behave, not what to believe’. Once the Christian dissociates himself from the people, from the State, from the cultural community, from the judicial system, he rejects training, knowledge, education, the acquisition of goods, action, becoming apolitical and anti-nationalist, neither aggressive nor defensive. A Christian should be one who does not want to be a

soldier, who is not interested in justice, who does not ask to join the police, who endures any suffering to ensure inner peace. Nietzsche mocks those who believe they can overcome Christianity through the natural sciences. 'Christian value judgments are not at all overcome by this; 'Christ on the cross' remains the most exalted symbol’.

Nietzsche is completely alien to the principles of Christian morality: religious individualism, awareness of sin, humility, concern for the salvation of the soul. He opposes the idea of repentance: 'I don't love this kind of cowardice in the face of what has been done; one should not succumb to a sudden feeling of unexpected shame and remorse. Extreme arrogance must stand firm on this point. And, ultimately, what good is repentance?! No action can be cancelled simply because you regret having committed it...' Nietzsche does not intend here to attenuate responsibility, but rather to intensify it. In this case, the one who knows how much courage and pride are required to assert oneself in the face of fate speaks. From the perspective of his amor fati, Nietzsche speaks disparagingly of Christianity 'with its perspective of bliss'. As a man of the north, Nietzsche does not understand why he should be 'redeemed'. The Mediterranean religion of redemption remains completely alien to its Nordic nature. Nietzsche understands man only as someone who fights against fate: he finds incomprehensible a way of thinking that sees only punishment in struggle and action. 'Our real life is a false, rejected and sinful existence, a punitive existence...' Pain, struggle, work, death is assumed as objections directed to life. ‘The innocent, idle, immortal, happy man: it is necessary to criticize first of all this vision that stands at the top of all our desires’. With particular vehemence, Nietzsche rages against the monastic contemplative life, against the Augustinian image of the 'Saturday of Saturdays'. He praises the fact that with Luther the contemplative life has come to an end. At this point, the Nordic tonality of the struggle and activity resonates loud and clear. The tone with which we utter these words today we first hear from Nietzsche.

Nietzsche is for us the philosopher of heroism. But this is only a half-truth if we do not also understand him as the philosopher of activism. Nietzsche perceived himself as Plato's historical antagonist. The 'works' do not arise from contemplation, from the recognition of transcendent values, but are the result of exercise, of a doing repeated again and again. In order to make it understandable, Nietzsche uses a well-known antithesis. 'The works, first and foremost! This means exercise, exercise, and even more exercise! The faith inherent in it will arise by itself, be assured of that!' In contrast to the Christian proscription of the political sphere, and especially of the sphere of action, Nietzsche presents the phrase with which he overcomes the opposition between Catholicism and Protestantism (faith-works): 'One must exercise oneself not in the strengthening of

the feeling of value, but in doing; One must above all be capable of something.' With this, he restores the purity of the sphere of action, of politics.

'Values' in the Nietzschean sense do not constitute an afterlife and therefore cannot be converted into dogmas. In us, through us, values compete for supremacy: they exist as long as we support them. When Nietzsche urges us in this way: 'Be faithful to the earth!', he reminds us that the idea is rooted in our strength, without waiting for its 'realization' in a distant beyond. But simply mentioning the 'hereafter' of values in Nietzsche is not enough, unless one intends to refute at the same time the idea that 'values are realized through action'. There is always something subordinate in the 'realization' of values, whether immanent or transcendent values.

Through the risk inherent in action, values arise from a force of their own on which any true ordering among men is built. Prominent forms of historical life will never be realized by an individualistic morality, even if it has an individualistic- religious foundation. According to Nietzsche, common morality has paralyzed the spirit of action, making it impossible to establish historical orders. As a consequence, there are only individual souls and no community that does not have only a provisional value, or types or 'forms of homogeneous activity of long duration'. However, the individual is not given the opportunity to assert himself as such, so everything becomes a staging. 'Therefore, everything is transformed into a mise-en-scène. Modern man lacks the sure instinct (consequence of forms of homogeneous and long-lasting activity in a certain human type); hence the inability to accomplish anything; He never fixes on his shortcomings as an individual.' We are absolutely far from the perfection of being, doing and wanting. 'The effort of will that extends over a long period of time, the choice of conditions and valuations that give the possibility of disposing of the coming centuries, that is truly the anti-modern in the highest sense of the term. Dissolute principles give our epoch characteristics such as the redundant development of intermediate areas, the decline of rates. On the other hand, National Socialism means the recovery of organizational principles and selective discipline.

Nietzsche regards the 'staging' of modern man fundamentally as a result of the morality of 'free will'. This morality is closely related to the generalized overvaluation of conscience. ‘How wrong it is that the value of an action should depend on what precedes it in consciousness’. 'All perfect actions are unconscious and involuntary; conscience expresses an imperfect and often sickly personal condition. The degree of consciousness makes perfection impossible... a form of staging'. 'As a soldier trains, so man must learn to act. In fact, this unconsciousness belongs to any kind of perfection: even the mathematician unconsciously uses

his own combinations...'. Unconsciousness, exercise, perfection. 'We must seek perfection where consciousness is least acquired... Righteousness and cunning stored up by generations, who have never become aware of their principles or have even felt a small shudder in front of them. And this is something very different from the liberal doctrine of 'personality' which possesses a) principles and b) an individuality capable of being stronger than its own principles. Nietzsche starts not from principles, but from value evaluations corresponding to a certain human typology and useful for its conservation, where this 'conservation' should not be understood too quickly: with this term, Nietzsche refers to the conservation of the human typology together with all its values. ‘All assessments refer to a specific perspective: the preservation of the individual, of a community, of a race, of a State, of a Church, of a faith, of a culture’. Nothing exists that, without relating to an existence, has value in itself. Values express existential conditions. Therefore, false values are not eradicated by principles: existence confronts existence.

The Nietzschean determination of values, which is Nordic and warlike, is opposed to the Mediterranean and priestly determination of values. The Nietzschean critique of religion is a critique of the priest and starts from the position of the warrior, at the moment when Nietzsche demonstrates how even the origin of religion is within the realm of power. From this follows the disastrous contradiction of morality based on the Christian religion. ‘For moral values to reach dominion, it is necessary that they be put at the service of immoral forces and affections. The birth of moral values is, therefore, the work of immoral affections and considerations’. Morality thus turns out to be the work of immorality. 'How to bring virtue to predominance: this treatise concerns the great politics of virtue'. Here this doctrine is expressed for the first time: 'It is possible to achieve the predominance of virtue by the same means by which one is generally mastered, in any way, not by virtue.' 'It is necessary to be very immoral in order to become moral by action...'. Instead of bourgeois moral philosophy, Nietzsche establishes the philosophy of the will to power, that is, political philosophy. If he becomes a praiser of the 'unconscious', the latter should not be understood in the sense of depth psychology. Nietzsche is interested not so much in the unconscious impulses of the individual, but in the 'unconscious' understood as 'perfection' and 'potentiality'. In addition to this, the unconscious means life as a whole, the organism, the 'great reason' of the body.

Consciousness is only a tool, a particularity in life as a whole. Nietzsche contrasts the aristocratism of nature with consciousness. However, for millennia, a morality hostile to life has opposed the aristocratism of the healthy and strong. Like National Socialism, Nietzsche perceives in the state and in society the 'great

agent of life', who must be accountable to the very life of any failed life. 'Humanity wants the decline of the unsuccessful, the weak, the degenerate: but Christianity opposes all this as a conservative force...'. At this point we find the fundamental antithesis: it originates either from a context of natural life or from the equality of individuals before God. On this last statement is based, in the last analysis, the democratic egalitarian ideal, while the first contains the fundamental features of a new politics. In the desire to found the State on race lies an unprecedented audacity. A new order of things must result. It is this order that Nietzsche wanted to erect in opposition to the existing one. But what about the individual? Become an individual in a community again. The instinct of the herd is very different from the instinct of an 'aristocratic society'. In the latter reappear those strong and natural men who do not let their primal instincts wither away for the benefit of utilitarian mediocrity, men who cultivate their passions instead of weakening or annihilating them. On the other hand, the individual cannot comprehend all this. It takes a long time for affections to be 'tyrannized', and this can only be achieved by one community, one race, one people.

The justification of passion, of the body, of nature is, in the first place, a justification of reality. By imagining a creative subject, an author of total reality, Nietzsche perceives the 'innocence of becoming'. The Nietzschean task is to reintegrate the two spheres: that of reality and nature, on the one hand, and that of history on the other. They are the same spheres and the same reintegration undertaken by National Socialism. Instead of absolutely artificial antitheses based on the scheme of good and evil, in this case the hierarchical order of the best and the worst intervenes. And in light of this natural hierarchical order, history takes on a new meaning.

The manly era, the age of soldiers and craftsmen, heralded by Nietzsche, is about to begin. Each civilization redefines in its own way the relationship between man and woman. While the role that men will assume in the next era is clear, that of women is not yet clear. Women too must find their place in the new context. In this regard, read what Nietzsche wrote about the Greek woman.

The Nordic approach, realistic and virile, expresses first of all its distrust of 'happiness', 'bliss' and 'leisure in contemplative states', finding itself now in the vision of a loved one (in 'love'), now in the vision of the work of art. Man does not seek pleasure or avoid pain. Following the will to power, Nietzsche teaches that he seeks conflict, since the will to power is the will to overcome fate. 'How the maximum degree of endurance must be continuously exceeded to stay on top! This is the measure of freedom for both the individual and society: that is, freedom understood as positive power, as the will to power’. The upper type grows where maximum resistance must be constantly overcome. 'One

must impose oneself to be strong, otherwise one will never be’.

If there is an authentically German expression, it is precisely this: 'We must impose ourselves to be strong, otherwise we will never be'. We Germans know well what it means to overcome adversity. We fully understand the 'will to power', although in a completely opposite sense to what our adversaries assume. In this sense, Nietzsche has also said something very profound: 'We Germans want something that is not yet required of us, we want something more!'

When we see German youth marching under the swastika badge today, we are reminded of Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations, where this generation is evoked for the first time. Our supreme hope is that the state will open up to these young people today. And when we greet this same youth with the cry of 'Heil Hitler', it is as if at the same time we are addressing our greeting to Friedrich Nietzsche.

A very small part of this work, related to the relationships between reality and images, archetypes, symbols, opinions, and figures, was carried out at the actual work of the author (facien03@uchile.cl).

REFERENCES

⦁ Baeumler, M. (1977). Bemerkungen zu Mazzino Montinaris Interpretation Alfred Baeumler. Annali

- Istituto Universitario Orientale Napoli. Sezione Germanica. Studi Tedeschi. 7, 117-122.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2018). Obras completas. Vol. IV. Escritos de madurez II y Complementos a la edición. 1ª ed., reimp ed.; Tecnos: Madrid, Vol. 4.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2005). Correspondencia I: Junio 1850- Abril 1869. Editorial Trotta: Madrid.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2007). Correspondencia II: Abril 1869-Diciembre 1874. Trotta: Madrid.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2009). Correspondencia III: Enero 1875 - Diciembre 1879. Editorial Trotta: Madrid.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2009). Correspondencia IV: Enero 1880 - Diciembre 1884. Editorial Trotta: Madrid.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2011). Correspondencia V: Enero 1885 - 23 de Octubre de 1887. Trotta: Madrid.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2012). Correspondencia VI: 23 de Octubre de 1887 - Enero1889. Trotta: Madrid.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2018). Obras completas Vol. I. Escritos de juventud. 2ª ed., corr. reimp ed.; Tecnos: Madrid, Vol. 1.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2018). Obras completas. Vol. II. Escritos filológicos. 1®. ed., reimp ed.; Tecnos: [Madrid].Vol. 2.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2014). Obras completas. Vol. III. Obras de madurez I. Tecnos: Madrid. Vol. 3.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2010). Fragmentos póstumos. Vol. I. (1869-1874). 2ª ed. corr. y aum ed.; Tecnos: Madrid. Vol. 1.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2008). Fragmentos póstumos. Vol. II. (1875-1882). Tecnos: Madrid. Vol. 2.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2010). Fragmentos póstumos. Vol.

III. (1882-1885). Tecnos: Madrid. Vol. 3.

⦁ Nietzsche, F. (2008). Fragmentos póstumos. Vol.

IV. (1885-1889). Segunda edición ed.; Editorial Tecnos (Grupo Anaya, S.A.): España. Vol. 4.

⦁ Lehmann, G. (1943). Die deutsche Philosophie der Gegenwart. Alfred Kröner: Stuttgart.

⦁ Bauemler, A. (1934). Nietzsche und der Nationalsozialismus. Nationalsozialistische Monatshefte, 289-298.

⦁ Bauemler, A. (1937). Studien zur deutschen geistesgeschichte. Junker und Duennhaupt: Berlin, p 281-294.