Epictetus on the Jews

Miguel Serrano collected works https://archive.org/details/miguel-serrano_202312

Epictetus on the Jews

Karl

Nov 12, 2023

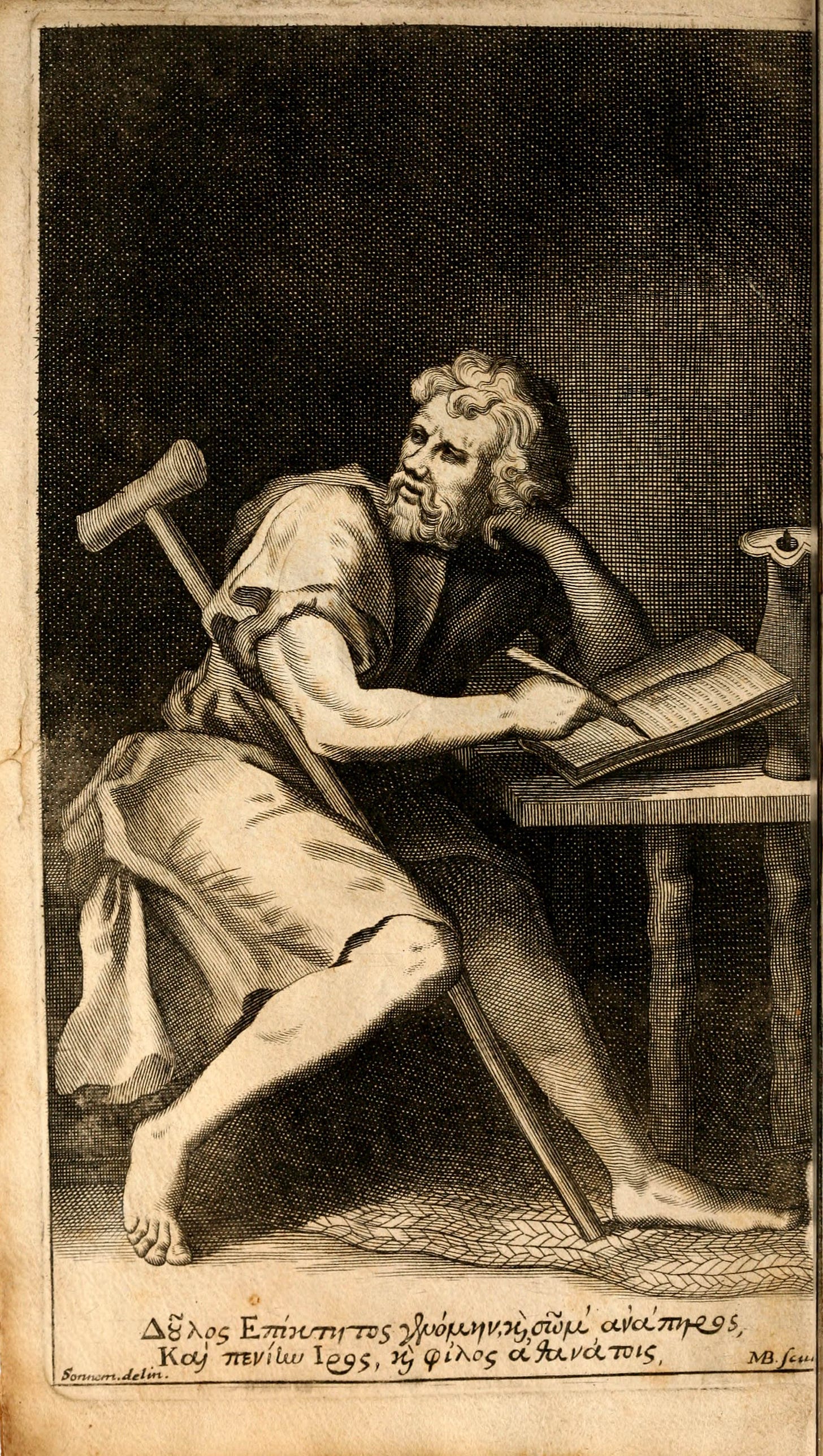

Epictetus is a well-known philosophical name to this day as being that of a Greek Stoic philosopher who rose from obscurity as a Greek slave in Turkey to being one of the greatest Roman thinkers of his day: who profoundly influenced Marcus Aurelius' 'Meditations'. Those readers who know of Epictetus have likely read or heard of 'The Golden Sayings of Epictetus', but this is a later compilation of Epictetus' witty and rather incisive points and epigrams.

One aspect of Epictetus' thought that doesn't get commented on a great is - like later philosophers like Porphyry of Tyre - (1) is his use of jewish dietary habits as a base from which to sally out to attack and make fun of the jews. What little we have of Epictetus' writings - i.e., only his 'Discourses' and his 'Enchiridion' remain - mention the jews in three passages and in none of them does Epictetus have anything positive or even particularly neutral to say about them.

In his 'Discourses' Epictetus is discussing the relation of diet and religion and to illustrate the point he brings up the different religious rules that are prevalent in the issue of meat-eating when he then says:

'Come tell me, do all things which seem to some persons to be good and becoming rightly appear such; and at present as to Jews and Syrians and Egyptians and Romans, is it possible that the opinions of all of them in respect to food are right? "How is it possible?" he said. Well, I suppose it is absolutely necessary that, if the opinions of the Egyptians are right, the opinions of the rest must be wrong: if the opinions of the Jews are right, those of the rest cannot be right. "Certainly." But where there is ignorance, there also there is want of learning and training in things which are necessary. He assented to this.' (2)

This passage is the clarified by Epicetus' next comment on jewish dietary habits:

'Precognitions are common to all men, and precognition is not contradictory to precognition. For who of us does not assume that Good is useful and eligible, and in all circumstances that we ought to follow and pursue it? And who of us does not assume that justice is beautiful and becoming When, then, does the contradiction arise? It arises in the adaptation of the precognitions to the particular cases. When one man says, "He has done well: he is a brave man," and another says, "Not so; but he has acted foolishly"; then the disputes arise among men. This is the dispute among the Jews and the Syrians and the Egyptians and the Romans; not whether holiness should be preferred to all things and in all cases should be pursued, but whether it is holy to eat pig's flesh or not holy.' (3)

In both these passages Epictetus uses the jews as an 'other' in so far he uses them a prime example of an alien culture and civilisation to the Romans that would have been partly familiar to most of his readers. In this he notes that one of the prime differences between Roman and jews habits is over whether it is holy or unholy to eat pork precisely because Epictetus regards the jewish religious concept of not eating pork to be a positive in a negative.

To explain: Epictetus is saying that he strongly disapproves of Judaism's focus on religious legalism and what is and is not permitted, but in spite of his general disapproval Epictetus seems to approve of the specific rejection of the eating of pork but specifically disapproves of the fact that this does not alter jewish dietary habits in regard to meat-eating more generally.

What Epictetus is arguing is something akin to Martin Luther's later argument of 'justification by faith alone' in that it is not the external form of religion that is important per se, but rather the quest of personal holiness regardless of the rituals and dogmas. Epictetus is also anticipating Arnold Toynbee's criticism of Judaism when he called it a 'fossil religion' and rightly suggested that it was 'obsessed with legal wrangling' in that he is suggesting that Judaism - then as now - is a religion that is focused on 'thou shalt not' - i.e., ritual form - rather than the quest for personal spiritual perfection.

In a sense what Epictetus is saying is that religion should be about an altruistic relationship with the deity or deities (i.e., his notion of Kantian 'pure religion') rather than the egoistic bombastic show of ritual and dogma that Epictetus tacitly suggests characterises Judaism and elements of Roman religion that has been corrupted by it and other Eastern cults such as that of Isis.

Thus, what Epictetus is arguing is ipso facto that jews are a corrupting influence on Imperial spirituality as they are obsessed with the externals of religious form rather than the internalisation of faith, which is what Epictetus advocated.

To Epictetus the jews worshipped a proverbial meaningless idol made of nothing but their own compressed egoism. Where trying to be more devout and orthodox than each other had become a form of materialistic competition, rather than the pure internal religion that he advocates. In essence Epictetus viewed jews as carriers of subversive religious ideas, which destroyed the internal natural religiosity of the Roman people.

This is also the double meaning inherent in Epictetus' phrase about the 'ignorant' in that where there is ignorance: learning and training are required. This Epictetus is applying to the Roman people who he feels need to throw off their superstitious ways and stop trying to conform to the externals of religious worship and seeking short-term satisfaction in the mystery cults of Yahweh (jews) and Isis (the reference to the Egyptians) - which if he we remember our Suetonius - were a serial political problem for the Imperial authorities because they were almost ipso facto subversive. (4)

Epictetus’ dislike of the jews and view of them as a subversive sect is brought out in its most complete form in the last passage to mention jews in his 'Discourses':

'Why then do you call yourself a Stoic? Why do you deceive the many? Why do you act the part of a Jew, when you are a Greek? Do you not see how each is called a Jew, or a Syrian or an Egyptian? And when we see a man inclining to two sides, we are accustomed to say, "This man is not a Jew, but he acts as one." But when he has assumed the affects of one who has been imbued with Jewish doctrine and has adopted that sect, then he is in fact and he is named a Jew. Thus we too being falsely imbued, are in name Jews, but in fact we are something else. Our affects are inconsistent with our words; we are far from practising what we say, and that of which we are proud, as if we knew it.' (5)

In the just quoted passage we see Epictetus discussing the issue of the 'god-fearer' - i.e., those who wished to serve the jews as helpers but could not or did not wish to convert - when he names a man a Greek who is acting like a jew. Or rather to transliterate it more meaningfully: a Greek who is aiding the jews as a 'god-fearer' and thus behaving like a jew.

In this Epictetus tells us he betrays everything he is internally for the external form of an alien religion, which bears no relation to his internal desire towards the pure religion of his nature. In essence: the Greek has exchanged true worship for the trappings of religious ritual.

Ergo the jews are subversive to Epictetus because they are taking the Greeks and Romans away from their internal religion and towards an alien one that bears no relation to their true desires, but rather fulfils an immediate decadent need on their part for meaningless religious ritual.

We also see that Epictetus identifies the jews not as a mere religious grouping, but rather a nation who happen to also have a national religion.

This is explained by Epictetus when he characterises the typical understanding of the time was that if you had been 'imbued with Jewish doctrine' (i.e., converted or became a 'god-fearer') and 'adopted that sect' (i.e., forsworn your loyalty to Rome and re-sworn it to the jews) then you were a jew 'in fact' and 'in name'. However, Epictetus rightly notes that this is incorrect and that you are 'something else' (i.e., Greek and not a jew): he also anticipates a racial interpretation of the jewish question by arguing that what the hypothetical Greek 'effects' (i.e., how we actually think and act) is inconsistent with 'his words' (i.e., his profession of jewishness).

Or put simply: Epictetus is saying that a non-jew cannot become a jew any more than a jew can become a non-jew, because the two innate natures are different regardless of what each many outwardly profess to believe.

Epicetus also tells us that it is the custom among the subjects of the Roman empire to distinguish between jews and non-jews by mere behaviour, which suggests that the jews at this time were developing a reputation that made them distinctive within the empire and from the context: we have to conclude that that distinct reputation was not a favourable one.

If we thus combine Epictetus view of the innately differing natures of jews and non-jews with his idea that the pure religion is our internal faith rather than the external trappings that it is placed within (and it is important to be true to your internal faith). Then it becomes clear - with the addition of the note of his dislike of the jews - that Epictetus is arguing for a form of proto-racial understanding of the jewish question as one that goes beyond the borders of mere religion and culture, but right to the inner souls of men.