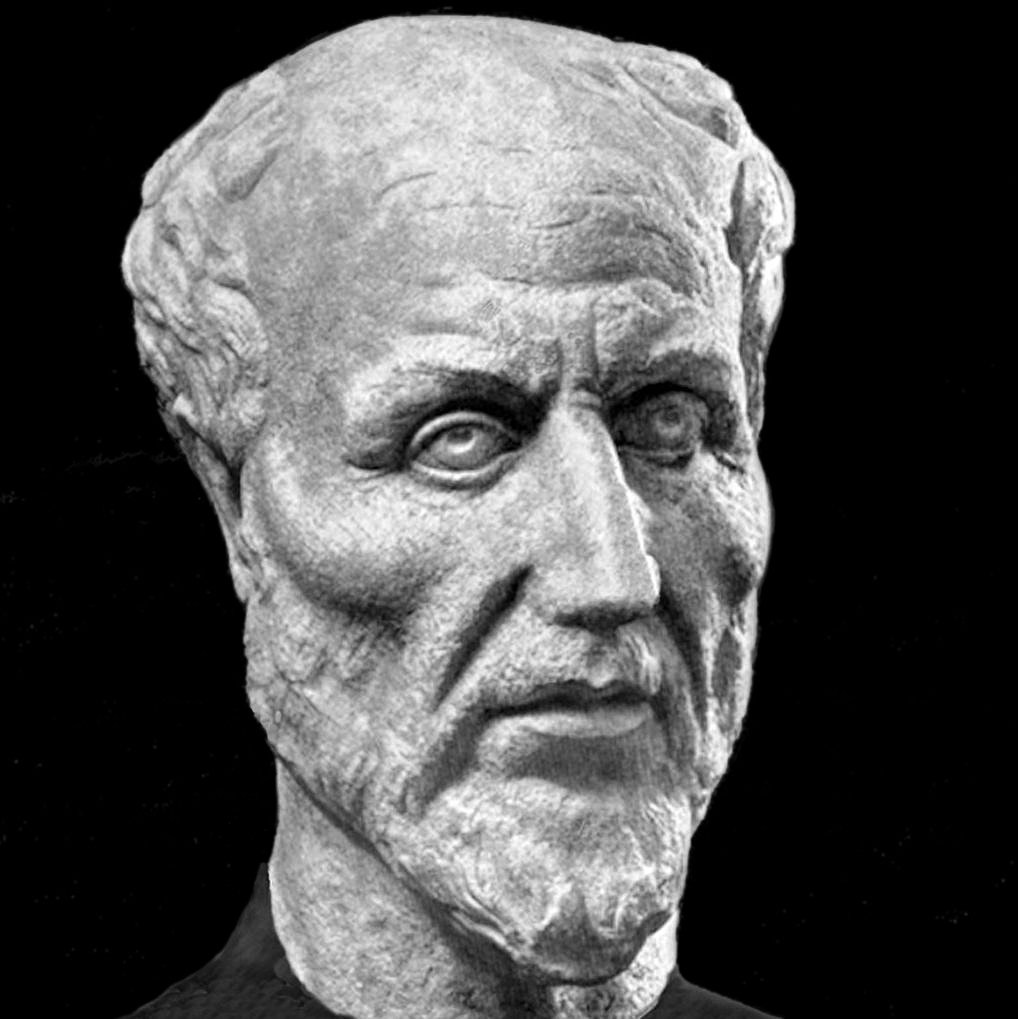

Plotinus

Maxims of Pagan Wisdom

It is for the gods to come to me: not for me to go to them.

1

his reply, given by Plotinus to Amelius, who invited him to approach the

gods with the prescribed rituals, reflects the spirit of the “solar” path. The

surpassing of the religious attitude; the transcendent dignity of the man in

possession of Wisdom, whom Plotinus terms the σπουδαῖος; his superiority not

only to the natural world, but also to the divine world: all these are affirmed

here.

It is a matter of an inner attitude that is fundamental for practice.

One must create a quality in oneself by which the suprasensible powers (the

gods) are constrained to come, like females attracted by the male. This quality is

summarized in one verb, which means nothing and yet means everything:

TO BE -BE, CONSIST, make yourself a center. Through “ascesis,” through “purification,”

through what Plotinus himself will explain. You have heard tell of the “dry

way.” This is an aspect of it. Separate yourself from those who are attracted to

the invisible worlds through vague neediness, soulful yearning, and confused

vision—more “nonbeings” than “beings.”

You must make yourselves like the gods; not like good men. The end is

not to be sinless, but to be a god.

2

These maxims cleanly separate the initiate’s path from the path of men. The

“virtue” of men, in the final analysis, is a matter of indifference: the image of an

image, as Plotinus says. “Morality” has nothing to do with initiation. Initiation is

a radical transformation from one state of existence into another state of

existence. A “god” is not a “moral example”: it is an other being. The good man

does not cease to be “man” through being “good.” In every time and place that

understands what “initiation” means, the idea has always been the same. Thus, in

Hermetism: “Our work is the conversion and the changing of one being into

another being, of one thing into another thing, of weakness into strength . . . of

corporeity into spirituality.”

3

Sinners can also draw water from the rivers. The giver does not know

what he is giving but simply gives.

4

How does man stand with respect to the all? As a part? No. As a whole

that belongs to itself.

Lacking unity, things are deprived of “ being.” The more unity, the more

being they possess.

Every being is itself by belonging to itself; and belonging to itself, it

concentrates itself. As Unity, it possesses itself, and has all the grandeur,

all the beauty. Therefore do not run and flee from yourself indefinitely.

Everything within is now gathered into its unity.

5

The essential element for the condition of “being” is unity.

UNIFY YOURSELF—BE ONE

This bundle of energes, this horde of beings, sensations, and tendencies that

make up you: bend them beneath a single law, a single will, a single thought.

ORGANIZE YOURSELF

Bend your “soul,” use it in every way, take it to every crossroads until it is inert,

incapable of its own movement, dead to every instinctive irrationality. Just as a

perfectly trained horse, when ordered, goes to right or left, stops, or leaps ahead,

so your soul must be to you: a thing that you hold in your fist. Unchained, you

will be one: being one, you are—and it belongs to you. Belonging to you, you

will possess grandeur.

Ancient classical wisdom distinguishes two symbolic regions: the lower, of

things that “flee”; the upper, of “things that are.” What flow or “flee” are the

things that cannot attain the realization and perfect possession of their own

nature. The other things, are: they have transcended this life, which is mixed

with death and is a ceaseless running and aiming. Their “immobility” and even

the ancient astronomical designation of their “place” are symbols, denoting a

spiritual state. To be one, no longer dispersed, follows.

What is the Good for such a man [for the σπουδαῖος]?

He is himself his own good. The life that he possesses is perfect. He

possesses the good in that he seeks nothing else.

To take away what is other with respect to your own being is to

purify yourself.

In simple rapport with yourself; without obstacle to your pure unity;

without anything mingled within this purity, being solely yourself in pure

light . . . you have become a vision.

Though being here, you have ascended.

You have no more need for a guide.

Fix your glance. You will see.

6

With marvelous conciseness, this expresses what is to be called “good” in the

transcendent sense: the absence of anything that can penetrate you and draw you

out of yourself by a desire or impulse. Plotinus takes care to define the spiritual

significance of such a concept, saying that the superior man can still “seek other

things, inasmuch as they are indispensable not to him, but to his neighbor: to the

body that is joined to him, to the life of the body that is not his life. Knowing

what the body needs, he gives it: but these things in no way intrude upon his

life.”

7

“Evil” is the sense of need in the spirit: that of every life incapable of

governing itself, that stumbles around, desiring, striving to complete itself by

obtaining something or other. As long as this “need” exists, as long as there is

this inner and radical insufficiency, the Good is not there. It is nothing that can

be named: it is an experience that only an act of the spirit on the spirit can

determine: separating itself from the idea of any “other,” reuniting with itself

alone. Then there arises a state of certainty and plenitude in which, once given,

one asks for no more, finding all speech, all speculation, all agitation useless,

while one knows of nothing more that could cause a change in one’s inmost

soul. Plotinus rightly says that this being which totally possesses its own life

possesses perpetuity: being solely “I,” nothing could be added to it either in the

past or the future.

The state of being is in the present being.

Every being is in act, and is act.

Pleasure is the act of life (ἡ ἐνέργεια τῆς ζωῆς).

Souls can be happy even in this universe. If they are not, then blame

them, not the universe. They have surrendered in this battle, where the

reward crowns virtue.

8

Plotinus again specifies the meaning of “being”: it is to be present, to be in

action. He speaks of “that sleepless intellectual nature” (ἡ φύσις ἄγρυπνας), a

strictly traditional expression. We know of the terms “the Awakened,” the “Ever

Wakeful,” and the symbolism of “sleep,” which besides may be more than

symbolism, referring to the continuity of a “present being” that undergoes no

alteration even in that change of state which habitually corresponds to sleep.

Being, then, is being awake. The experience of the whole being gathered in

an intellectual clarity, in the simplicity of an act: that is the experience of

“being.” To abandon oneself, to fail—that is the secret of nonbeing. Fatigue in

the inner unity, which slows and disperses, the inner energy that ceases to

dominate every part, so that as it crumbles a mass of tendencies, instincts, and

irrational sensations arise: this is the degradation of the spirit manifesting in ever

more deviant and senseless natures, to the limiting point of dissolution that is

expressed in matter. Plotinus asserts that it is incorrect to say that matter “is”:

the being of matter is a nonbeing. Its indefinite divisibility indicates the “fall”

from unity that it represents; its inertia, being heavy, resistant, and blunt, is the

same as applies to a person who is fainting, cannot hold himself upright, and

collapses. It is of no importance that physical knowledge has its own and

different “truth.” Corporeal being is the nonbeing of the spiritual.

As the present state of culmination, “being” is identical with “good.” Thus

“matter” and “evil” are identical in their turn, and there is no other “evil” beside

matter. Here we must abandon current opinions. The “evil” of men has no place

in reality, hence none in a metaphysical vision, which is always a vision

according to reality. Metaphysically, the “good” and “bad” do not exist, but

rather that which is real and that which is not—and the degree of “reality”

(understood in the spiritual sense already explained as “being”) measures the

degree of “virtue.” In the view of ancient classical man, only the state of

“privation of being” was “evil”: fatigue, abandonment, the sleep of the inner

strength, which at its limit, as we have said, determines “matter.” Therefore

neither “evil” nor “matter” are principles in themselves: they are derivative states

due to “degradation” and “dissolution.” Plotinus expresses himself exactly in

these terms: “It is by failure of the Good that the darkness is seen and that one

lives in darkness. And evil, for the soul, is this failure that generates darkness.

Such is the first evil. The darkness is something that proceeds from it. And the

principle of evil does not reside in matter, but before matter [in the cessation of

action, which gave matter its origin].”

9

Plotinus adds: pleasure is the act of life. It is the view already affirmed by

another great mind of the ancient world—by Aristotle, who had taught that every

activity is happy inasmuch as it is perfect. Such are happiness and pleasure in the

form of purity and liberty: those things that spring from the act that is perfected,

and which thereby realizes the one, “being,” the Good—not those passive things,

seized by means of the turbid satisfaction of desires, needs, instincts. Once again

we are led to the nonhuman point of view of “reality.” Even in the case of

happiness, the degree of “being” is the secret and the measure.

Consequently, Plotinus affirms that souls can be happy even in this universe,

thereby bringing to light an important aspect of the pagan concept of existence.

If “virtue” as dominating spiritual actuality implies power, one may understand

how the “good” is no more to be separated from “happiness” than glory from

victory. Whoever is defeated by an external or internal bond is not “good”: and it

would be unjust for such a being to be happy. But it is only the being that passes

judgment on itself, not the world.

Obviously, things are different for those who reduce “virtue” to a simple

moral disposition.

It is all very well to say “my kingdom is not of this world” and wait for a

god to give happiness in the beyond as a reward to the “just” who, lacking

power, have suffered injustice in this life and borne it with humility and

resignation. The truth of the warrior and hero of the ancient classical world was

otherwise. If “evil” and all its materialization in onslaughts and limitations by

lower forces and bodily things has its root in a state of degradation of the good—

it is inconceivable, and logically contradictory that it should persist as the

principle of unhappiness and bondage in regard to him who has destroyed that

root, having become “good.” If the “good” exists, then “evil”—suffering,

passion, servitude—cannot exist. Rather they mean that “virtue” is still

imperfect; “being” still incomplete; “purity” and unity still “tainted.’”

Some lack arms. But he who has arms should fight—no god is going to

fight for the unarmed. The law decrees that victory in war goes to the

brave, not to those who pray.

That cowards should be ruled by the wicked—that is just.

10

Here is a fresh affirmation of the virile spirit of the pagan tradition, a new

contrast with the mystico-religious attitude, and a disdain for those who

deprecate the “injustice” of earthly things and, instead of blaming their own

cowardice or accepting their impotence, blame the All or hope that a

“Providence” will take care of them.

“No god is going to fight for the unarmed.” This is the anti- Christian

cornerstone of every warrior morality;

11 and it relates to the concepts explained

above, concerning the identity (from the metaphysical point of view) of

“reality,” “spirituality,” and “virtue.” The coward cannot be good: “good”

implies a heroic soul. And the perfection of the hero is the triumph. To ask a god

for victory would be like asking him for “virtue”; whereas victory is the body in

which the very perfection of “virtue” is realized.

Fabius’s soldiers, when they set out, did not vow to win or die, but vowed to

fight and to return as victors. And so they did. The spirit of Rome reflects the

same wisdom.

From fear, totally suppressed, [the soul] has nothing to dread.

He who fears anything has not attained the perfection of virtue. He

is a half-thing (ἤμισὺς τις ἔσται).

12

Impressions do not present themselves to the superior man (τῶ

σπουδαῖος) as they do to others. They do not reach the inner being,

whether they are other things, pains and losses, his own or others’. That

would be feebleness of the soul.

If [suffering] is too much—so be it. The light in him remains, like the

lamp of a lighthouse in the turmoil of wind and tempest.

Master of himself even in this state, he will decide what is to be

done.

The σπουδαῖος would not be such if a daimon were acting within

him. In him it is the sovereign mind (νοῦς) that acts.

13

Plotinus admits that the superior man may sometimes have involuntary and

unreflective fears, but more as motions that are not part of him, and in which his

spirit is not present. “Returning to himself, he will expel them. . . . Like a child

who is subdued merely by the power of someone who stares at him.”

14

As for suffering, he can at most cause the separation of a part of himself not

yet exempt from passion: the higher principle is never overwhelmed. “He will

decide what is to be done.” Should the case arise, he can also quit the game. We

should not forget that according to Plotinus the σπουδαῖος is his own “daimon”

and lives somewhat like an actor playing a freely chosen role. Against the

Gnostic Christians, Plotinus retorts drily: “Why find fault with a world you have

chosen and can quit if you dislike it?”

15

Like the νοῦς in man, one can define exactly the principle of “being” made

from pure intellectuality: it is the “Olympian mind,” with respect to which the

“soul” principle (ψυχή) represents something peripheral: mostly it is a depth that

remains hidden and latent. But then it is not the “I” but a “daimon” that acts in

every deed. Plotinus says precisely that all that happens without deliberation

unites a daimon with a god. Now we will see how he describes the opposite

condition.

There the reason for being . . . does not exist as a reason, but as being.

Better said, the two things are one.

Each should be itself.

Our thoughts and actions should be our own. The actions of every

being should belong to it, be they good or bad.

When the soul has pure and impassive reason for its guide, in full

dominion of itself, wherever it wants to direct its energy: then alone the

action can be called ours, not another’s: from within the soul as a

purity, as a pure dominating and sovereign principle . . . not from an

action that is diverted by ignorance and split by desire Then

there would be passion and not action in us.

16

The sensations are the visions of the sleeping soul.

Everything of the soul that is in the body is asleep. The true

awakening is to exit from the body. To exchange existence with another

body is to pass from one sleep to another, from one bed to another.

Truly awakening is to abandon the world of bodies.

17

Since materiality is the state of unconsciousness for the spirit, any reality that

appears through the material senses is a sleeping reality. But we should not

interpret the exit from the body and the abandonment of the world of bodies in a

crude way: it is essentially a matter of an inward change, integrating oneself with

the “sleepless intellectual nature.” And this is the true initiatic and metaphysical

initiation.

Plotinus aptly compares the change of bodies as passing from one bed to

another. Even though it has a consistency, the doctrine of reincarnation could not

be better stigmatized as it is by this pagan initiate. On the “wheel of births” one

form is equivalent to another with respect to the center, which is equally distant

from any point on the circumference. Metaphysical realization is a fracture in

the series of conditioned states: a bursting open to transcendence. One does not

reach it by following the traces of those “fugitive” natures, those who pursue a

goal that they have placed outside themselves: in the world of bodies and

becoming.

All that one sees as a spectacle is still external; one must bring the

vision within; make yourself one with what you have to contemplate;

know that what you have to contemplate is yourself.

And it is you. Like someone possessed by the god Apollo or a Muse,

he would see the divine light blazing within, if only he had the power to

contemplate this divine light in himself.