The Demiurge

René Guénon

(published in La Gnose, Nov. 1909 and signed under the name Palingénius)

[About the superior meaning of Perfection]

There are a certain number of problems which have constantly preoccupied men, but perhaps none has ever seemed so insoluble as that of the origin of evil, a problem which most philosophers, and especially theologians, encounter as an insurmountable obstacle: Si Deus est, unde Malum? Si non est, unde Bonum? [If God is, whence Evil? If He is not, whence the Good?] In fact, this dilemma is insoluble for those who consider Creation as the direct work of God, and who, consequently, have to make him equally responsible for good and evil. One may well say that this responsibility is to a certain extent attenuated by the creatures’ freedom; but if the creatures can choose between good and evil, this means that both already exist, at least in principle; and if they are prone to sometimes deciding in favor of evil rather than being always inclined toward good, this is because they are imperfect. How then can God, if he is perfect, create imperfect beings?

Obviously the perfect cannot engender the imperfect, for, if that were possible, the perfect would have to contain within itself the imperfect in the principial state, and then it would no longer be the perfect. Therefore the imperfect cannot proceed from the perfect by way of emanation, and can only result from creation ex nihilo. But how can one accept that something can come from nothing, or, in other words, that anything can exist without having a principle? Moreover, to admit creation ex nihilo would be to acknowledge ipso facto the final annihilation of created beings, for what has a beginning must also have an end; and nothing is more illogical than to speak of immortality under such an hypothesis. But creation thus understood is an absurdity, for it is contrary to the principle of causality, which it is impossible for any reasonable man to deny sincerely; and we can say with Lucretius: Ex nihilo nihil, ad nihilum nil posse reverti [Nothing comes from nothing; nothing can revert to nothing].

There can be nothing that does not have a principle; but what is this principle? And is there in actual fact only one Principle of all things? If the entire universe is considered, it is certainly obvious that it contains all things, for all parts are contained within the whole. On the other hand, the whole is necessarily unlimited, for if it had a limit, whatever exceeded that limit would not be included within the whole, and this supposition is absurd. That which has no limit can be called the Infinite, and since it contains everything, this Infinite is the principle of all things. Moreover, the Infinite is necessarily one, for two Infinites that are not identical would exclude one another. Hence there is only one unique Principle of all things – and this Principle is the Perfect, for the Infinite can only be such if it is the Perfect.

Thus, the Perfect is the supreme Principle, the primal Cause; it contains all things potentially and it has produced all things. But then, since there is only one unique Principle, what becomes of all the opposites that are usually considered in the universe: Being and Non-Being, spirit and matter, good and evil? Hence we find ourselves again in the presence of the same question we posed at the outset; and we can now formulate the question in a more general way: how has unity been able to produce duality?

Certain people have found it necessary to admit two distinct principles opposed to each other; but this hypothesis is ruled out by what we said previously. In fact, these two principles cannot both be infinite, for they would then exclude each other, or else they would be identical. If only one was infinite, it would be the principle of the other. Finally, if both were finite they would not be true principles, because to say that what is finite can exist by itself amounts to saying that something can come from nothing – since whatever is finite has a beginning, logically, if not chronologically. Consequently, in the latter case, since both are finite they must proceed from a common principle, which is infinite, and so we are brought back to the consideration of one unique Principle. Furthermore, many doctrines usually considered dualistic are so only in appearance. In Manicheism as well as in the Zoroastrian religion, dualism was only a purely exoteric doctrine, concealing the true esoteric doctrine of Unity: Ormuzd and Ahriman are both engendered by Zervane-Akerene, and must merge in him at the end of time.

Hence duality is necessarily produced by unity, since it cannot exist by itself, but how can it be produced? In order to understand this, we must first of all consider duality under its least particularized aspect, which is the opposition between Being and Non-Being. Moreover, since both are necessary contained within the total Perfection, it is obvious in the first place that this opposition can only be apparent. It would thus be better to speak only of distinction; but of what does this distinction consist? Does it exist as a reality independent from us, or is it merely the result of our way of viewing things?

If by Non-Being one understands only pure nothingness, it is useless to speak about it, for what can be said about that which is nothing? But if Non-Being is considered as the possibility of being, then this is completely different. In this sense, Being is the manifestation of Non-Being and is contained in a potential state within Non-Being. The relationship of Non- Being to Being is then that of the non-manifested to the manifested, and it can be said that the non-manifested is superior to the manifested (of which it is the principle) since it contains potentially the whole of the manifested, plus that which is not, has never been, and never will be manifested. At the same time it can be seen that here it is impossible to speak of a real distinction, since the manifested is contained principially within the non-manifested. However, we cannot conceive the non-manifested directly, but only through the manifested; this distinction therefore exists for us, but only for us.

If such is the case for duality under the aspect of the distinction between Being and Non-Being, the same holds true with greater reason for all other aspects of duality. From this it is already easy to see how illusory is the distinction between spirit and matter, a distinction on which, nevertheless, so many philosophical systems are built, especially in modern times, as if on an unshakable basis; if this distinction disappears, nothing is left of all these systems. Furthermore, we can point out in passing that duality cannot exist without the ternary, for if in differentiating itself the Supreme Principle gives rise to two elements (which moreover are only distinct insofar as we view them as such), these two elements, together with their common Principle, form a ternary, so that in reality it is the ternary, and not the binary, which is directly produced by the first differentiation of the primordial unity.

Let us now come back to the distinction of good and evil, which too is only a particular aspect of duality. When good and evil are opposed to each other, the good is usually seen to lie in Perfection, or, at a lower degree at least, as a tendency toward Perfection, so that evil is then nothing other than the imperfect. But how could the imperfect oppose the Perfect? We have seen that the Perfect is the Principle of all things and that, on the other hand, it cannot produce the imperfect, from which it follows that in reality the imperfect does not exist, or at least that it only exists as a constituent element of total Perfection; but then it cannot really be imperfect, and what we call imperfection is only relativity. Thus, what we call error is only relative truth, for all errors must be included within total Truth, or else the latter, being limited by something external to itself, would not be perfect, which amounts to saying that it would not be the Truth. Errors, or rather relative truths, are only fragments of the total Truth, so that it is fragmentation that produces relativity, and consequently could be said to be the cause of evil – if relativity is really synonymous with imperfection. But evil is such only if it is distinguished from the good?

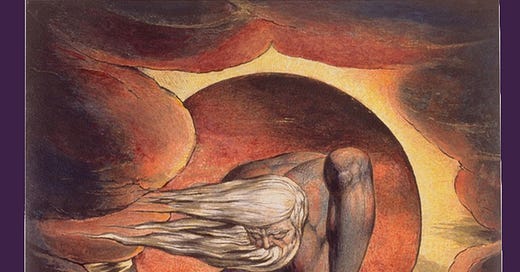

If the perfect is called good, the relative is not really distinct from it, since it is contained within it principially. Therefore evil does not exist from the universal point of view. It will exist only if all things are considered in a fragmentary and analytical light, separating them from their common Principle, instead of viewing them as contained synthetically within this Principle, which is Perfection. Thus is the imperfect created; in distinguishing from evil from good, both are created by this very distinction, for good and evil are such only when they are opposed to each other. If there is no evil, there is no longer any reason to speak of good in the ordinary sense of this word, but only of Perfection. It is thus the fatal delusion of dualism that realizes good and evil, and which, considering things from a particular point of view, substitutes multiplicity for unity, and thus encloses the beings who are under its spell within the sphere of confusion and division. This sphere is the Empire of the Demiurge.

II

What we have just said concerning the distinction of good and evil makes it possible to understand the symbol of the original Fall, at least insofar as such things can be expressed. The fragmentation of total Truth, or of the Word – for fundamentally they are the same thing – a fragmentation that produces relativity, is identical to the dismemberment of Adam Kadmon, whose separated fragments constitute protoplastic Adam, namely the first creator of forms. The cause of this segmentation is Nahash – egoism, or the desire for individual existence. Nahash is not the cause external to him only insofar as man himself exteriorizes it. This instinct of separativity, which by its very nature provokes division, includes man to taste the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, that is, to create the very distinction of good and evil. Thus man's eyes open, for what was internal to him has become external as a result of the separation that has arisen between beings; from now on beings assume forms which limit and define their individual existence, and so man was the first maker of forms. But henceforth he too is subject to the conditions of this individual existence and he also assumes a form, or, according to the biblical expression, a tunic of skin. He is enclosed within the sphere of good and evil, within the Empire of the Demiurge.

This essay, very abridged and incomplete though it is, makes it evident that the Demiurge is not a power external to man. In principle he is merely man's will, inasmuch as this will realizes the distinction between good and evil. But then man, limited as an individual being by this will which is his very own, regards it as something external to himself, and thus it becomes distinct form him. Furthermore, as it opposes the efforts he makes to escape from the sphere in which he has enclosed himself, he views it as a hostile power and calls it Satan or the Adversary. Let us note, moreover, that this Adversary, whom we ourselves created and whom we create moment by moment – for this should not be considered as having taken place at a given time – is not evil in itself, but is merely the whole of everything that is adverse to us.

From a more general point of view, once the Demiurge has become a separate power and is considered as such, he is the Prince of this World mentioned in Saint John's Gospel. Here again, strictly speaking, he is neither good nor bad, or rather he is both, since he contains within himself both good and evil. His sphere is regarded as the lower world, as opposed to the upper world or principial Universe from which it has been separated, but it should be carefully noted that his separation is never absolutely real. It is real only insofar as we realize it, for this lower world is contained potentially within the principial Universe, and it is obvious that no part can really depart from the Whole. This is what keeps the fall from going on indefinitely; however, this is only a purely symbolic expression and the depth of the fall simply measures the degree to which the separation is realized. With this reservation in mind, the Demiurge is opposed to Adam Kadmon or principial Mankind, manifestation of the Word, but only as a reflection, for he is not an emanation and does not exist by himself. This is what is represented by the two old men of the Zohar, and also by the two opposed triangles of the Seal of Solomon.

We are thus led to consider the Demiurge as a dark and inverted reflection of Being, for in reality he cannot be anything else. So he is not a being; but according to what we said earlier, he can be considered as the community of the beings to the extent that they are distinct, or if one prefer, insofar as they are endowed with individual existence. We are separate beings insofar as we ourselves create distinction, which only exists insofar as we create it. As creators of this distinction, we are elements of the Demiurge; and to the extent that we are distinct beings, we belong to the sphere of this same Demiurge, which is what we call Creation.

All elements of Creation, namely the creatures, are therefore contained within the Demiurge himself, and he cannot in fact draw them out of anything but himself, since creation ex nihilo is impossible. As Creator, the Demiurge first produces division, from which he is not really distinct, since he exists only inasmuch as division itself exists. And then, as division is the source of individual existence, which in turn is defined by form, the Demiurge should be considered as the form-maker, and as such he is identical to protoplastic Adam, as we have seen. One can also say that the Demiurge creates matter, understood in the sense of the primordial chaos that is the common reservoir of all forms. Then he organizes this chaotic and dark matter, in which confusion reigns, bringing forth from it the multiple forms the totality of which constitutes Creation.

Now, must one say that this Creation is imperfect? Certainly, it cannot be regarded as perfect; however, from a universal point of view, it is merely one of the constituent elements of total Perfection. It is imperfect only when considered analytically as separated from its Principle, and it is moreover in the same extent that it is the sphere of the Demiurge. But if the imperfect is merely an element of the Perfect, then it is not really imperfect, and consequently the Demiurge and his sphere do not really exist from the universal point of view, any more than does the distinction between good and evil. From the same point of view it also follows that matter does not exist: material appearance is only an illusion. However, one should not conclude from this that beings with a material appearance do not exist, for this would amount to succumbing to another illusion, that of an exaggerated and poorly understood idealism.

If matter does not exist, the distinction between spirit and matter thereby disappears. Everything must in reality be spirit, but spirit understood in a completely different sense form that attributed to it by most modern philosophers. In fact, while opposing spirit to matter, they still do not consider spirit as independent of all form, and one may then wonder in what way it is differentiated from matter. It if is said that spirit is unextended whereas matter is extended, how then can that which is unextended assume a form? Moreover, why should one want to define spirit? Whether by thought or otherwise, one always attempts to define it by means of a form, and then it is no longer spirit. In reality, the universal spirit is Being, and not such or such a being in particular, but the Principle of all beings, and thus it contains them all. This is why everything is spirit.

When man reaches real knowledge of this truth, he identifies himself and all things with the universal Spirit. Then all distinctions vanish for him, so that he contemplates everything as being within himself, and no longer as external, for illusion vanishes before Truth like a shadow before the sun. By this very knowledge, then, man is freed from the bonds of matter and individual existence; he is no longer subject to the domination of the Prince of this World, he no longer belongs to the Empire of the Demiurge.

III

From the preceding it follows that beginning with his earthly existence man can free himself from the sphere of the Demiurge, or the hylic world, and that this emancipation is achieved through gnosis, that is, through full knowledge. Let us further point out that this knowledge has nothing to do with analytical science, and does not imply it in any way. It is too widespread an illusion nowadays to believe that total synthesis can only be attained through analysis. On the contrary, ordinary science is quite relative, and, limited to the hylic world as it is, does not exist any more than this world, from the universal point of view.

Moreover, we must also point out that the different worlds – or, according to a generally accepted expression, the various planes of the universe – are not places or regions, but modalities of existence or states of being. This enables one to understand how a man living on the earth might in reality no longer belong to the hylic world, but to the psychic or even to the pneumatic world. It is this that constitutes the second birth; however, strictly speaking, this birth is only a birth into the psychic world, through which man becomes conscious on two planes but without yet reaching the pneumatic world, that is, without identifying himself with the universal Spirit. This last result is only obtained by the one who fully possesses the triple knowledge, by which he is forever liberated from mortal births; this is what is being expressed when it is said that only pneumatics are saved. The state of the psychics is, in short, only a transient state; it is that of the being that is already prepared to receive the Light, but that does not yet perceive it, that is not yet aware of the one and immutable Truth.

When we speak of mortal births, we mean the modifications of a being, its passage through multiple and changing forms. There is nothing here which resembles the doctrine of reincarnation, such as it is accepted by the spiritists and Theosophists, a doctrine which we might some day have the opportunity to explain. The pneumatic is freed from mortal births, that is to say he is liberated from form, hence from the demiurgic world. He is no longer subject to change, and, consequently, is actionless; we shall come back to this point later. The psychic, on the contrary, does not pass beyond the World of Formation, which is symbolically designated as the first heaven or the Sphere of the Moon. From there he comes back to the terrestrial world, which does not in fact mean that he will actually take a new body on earth, but simply that he will need to assume new forms, whatever they may be, before obtaining Liberation.

What we have just said illustrates the agreement – we could even say the real identity, despite certain differences of expression – of the gnostic doctrine with the Eastern doctrines, particularly with the Vedānta, the most orthodox of all the metaphysical systems based on Brahmanism. This is why we can complete what we have said about the various states of the being by borrowing a few quotations from Self-Knowledge [Ātma-Bodha] by Shankarāchārya:

There is no other way of obtaining full and final Liberation than through Knowledge; it is the sole means which loosens the bonds of passion; without Knowledge, Beatitude cannot be obtained. Action, not being opposed to ignorance, cannot cast it away; but Knowledge dispels ignorance, as light dispels darkness.

Ignorance here means the state of a being shrouded in the darkness of the hylic world, attached to the illusory appearance of matter and to individual distinctions. Through knowledge, which is not within the sphere of action but superior to it, all these illusions vanish, as we said above.

When ignorance born of earthly affections is cast away, Spirit shines from the distance by Its own splendor in an undivided state, just as the Sun sheds its light when the cloud dispersed.

But before reaching this state, the being does through an intermediate stage corresponding to the psychic world. Then it no longer believes itself to be the material body but the individual soul, for all distinction has not vanished for it, since it has not yet departed the sphere of the Demiurge.

Imagining that he is the individual soul, man becomes frightened like a person mistaking a piece of rope for a snake. But his fear is dispelled by the perception that he is not the soul, but the universal Spirit.

The one who has become aware of the two manifested worlds, namely the hylic (the totality of gross or material manifestations) and the psychic (the totality of subtle manifestations), is twice born, dvija. But the one who is aware of the unmanifested universe or the formless world – that is, the pneumatic world – and who has achieved the identification of himself with the universal Spirit, Ātmā, he alone can be called yogi, that is to say united with the universal Spirit.

The Yogi, whose intellect is perfect, contemplates all things as abiding in himself and thus, through the eye of Knowledge, he perceives that everything is Spirit.

Let us note in passing that the hylic world is likened to the waking state, the psychic world to the dream state, and the pneumatic world to deep sleep. In this connection, we should recall that the unmanifested is superior to the manifested, since it is its principle. According to the gnostic doctrine there is nothing beyond the pneumatic Universe but the Pleroma, which can be viewed as constituted by the totality of attributes of the Divinity. This is not a fourth world, but is the universal Spirit itself, the Supreme Principle of the three worlds, neither manifested nor unmanifested, indefinable, inconceivable, and incomprehensible.

The yogi or pneumatic, for they are fundamentally the same thing, perceives himself no longer as a gross or subtle form, but as a formless being. Hence he identifies himself with the universal Spirit, a state which Shankarāchārya describes as follows:

He is Brahma beyond whose possession there is nothing to be possessed; beyond whose happiness once enjoyed there is no happiness which could be desired; and beyond whose knowledge once obtained there is no knowledge that could be obtained.

He is Brahma who having once seen, no other object is contemplated; with whom once identified, no birth is experienced; whom once perceived, there is nothing more to be perceived.

He is Brahma who is spread everywhere, all-pervading: in midspace, in what is above and what is below; the true, the living, the happy, non-dual, indivisible, eternal and one.

He is Brahma without size, unextended, uncreated, incorruptible, figureless, without qualities or character.

He is Brahma by whom all things are illuminated, whose light makes the Sun and all luminous bodies shine, but who is not made manifest by their light.

He himself permeates his own eternal essence and he contemplates the whole World appearing as being Brahma. Brahma does not resemble the World, and apart from Brahma there is nothing; whatever seems to exist apart from him is an illusion.

Of all that is seen, of all that is heard, nothing exists other than Brahma; and through knowledge of the principle, Brahma is contemplated as the real Being, living, happy, non-dual.

The eye of Knowledge contemplates the true, living, happy, allpervading Being; but the eye of ignorance does not discover It, does not catch sight of It, just as a blind man does not see the light.

When the Sun of spiritual Knowledge arises in the sky of the heart, It casts away darkness, pervades everything, embraces everything and illuminates everything.

Let us point out that the Brahma here in question is the superior Brahma. It should be carefully distinguished from the inferior Brahmā, for the latter is none other than the Demiurge, regarded as a reflection of the Being. For the Yogi there is only the superior Brahma, who contains all things and apart from whom there is nothing; for him, the Demiurge and his work of division no longer exist.

The one who has accomplished the pilgrimage of his own spirit, a pilgrimage in which there is nothing connected to the situation, the place, or the time, which is everywhere, in which neither heat nor cold are experienced, which bestows eternal happiness and freedom from all sorrow, that one is actionless; he knows everything and obtains eternal Beatitude.

IV

After having characterized the three worlds and the corresponding states of the being, and having indicated as far as possible what being is liberated from the demiurgic domination, we must once again return to the question of distinction between good and evil, in order to draw a few consequences from the preceding exposition.

First of all, one might be tempted to say that if the distinction between good and evil is sheer illusion, if it does not exist in reality, the same should hold true for morality, for moral standards are obviously based on this distinction, since they essentially imply it. But this would be going too far; morality does exist, but only to the same extent as the distinction between good and evil, that is, for anything that belongs to the sphere of the Demiurge; from the universal point of view, it no longer has any raison d'être. Morality, in fact, can apply only to action; now action implies change, which is only possible in the formal or manifested order. The formless world is immutable, superior to change, and therefore also to action; and this is why the being no longer belonging to the Empire of the Demiurge is actionless.

All of this shows that one should take great care never to confound the various planes of the universe, for what is said about one could be untrue for another. So, morality necessarily exists on the social plane, which is essentially the field of action, but it can no longer be in question when the metaphysical or universal plane is considered, since thenceforth there is no more action.

Having established this point, we should mention that the being that is superior to action nevertheless possesses the fullness of activity, but it is a potential activity, hence an activity that does not act. This being is not motionless, as might be wrongly said, but immutable, that is to say superior to change; indeed, it is identifies with Being which is ever identical to itself, according to the biblical formula 'Being is Being'. This must be compared with the Taoist doctrine, according to which the Activity of Heaven is non-acting. The sage, in whom the Activity of Heaven is reflected, observes non-action; nevertheless, the sage, whom we designated as the pneumatic or the yogi, can give the appearance of action, just as the moon appears to move when clouds pass over it; but the wind that blows away the clouds has no influence on the moon. Similarly, the agitation of the demiurgic world has no effect on the pneumatic; in this connection, we can again quote what Shankarāchārya says:

The Yogi, having crossed the sea of passions, is united with Tranquility and rejoices in the Spirit.

Having renounced these pleasures that are born of external and perishable objects, and enjoying spiritual delights, he is calm and serene like a lamp placed inside a jar, and rejoices in his own essence.

During his residence in the body, he is not affected by its properties, just as the firmament is not affected by what is floating within its bosom; knowing all, he remains unaffected by contingencies.

By this we can understand the real meaning of the word Nirvāna, to which so many wrong interpretations have been given. This word literally signifies extinction of the breath or of agitation, therefore the state of a being no longer subject to any agitation, ever free from form. At least in the West, it is a very widespread error to believe that when there is no more form, there is nothing, whereas in reality it is form that is nothing and the formless that is everything. Thus, far from being annihilation, as certain philosophers have contended, Nirvāna is on the contrary the plenitude of Being.

From all that has been said till now, one could draw the conclusion that one should not act; but this would again be inaccurate, if not in principle, at least in the application that one would like to draw from it. In fact, action is the condition of individual beings belonging to the Empire of the Demiurge. The pneumatic or the sage is really actionless, but as long as he resides in a body he gives the appearance of action. Externally, he is in all respects like other men, but he knows this is only an illusory appearance, and this is enough to set him truly free from action, since it is through knowledge that Deliverance is obtained. By the very fact that he is free from action, he is no longer subject to suffering, for suffering is merely the result of effort, hence of action, and it is this that constitutes what we call imperfection, although there is nothing imperfect in reality.

Obviously action cannot exist for the one who contemplates within himself all things as existing within the universal Spirit, without any distinction of individual objects, as is expressed in these words from the Vedas: 'Objects differ merely in designation, accident and name just as earthly utensils receive various names, although they are only different forms of earth.' The earth, principle of all these forms, is itself formless, but contains them all potentially; such also is the universal Spirit.

Action implies change, namely the unceasing destruction of forms which disappear in order to be replaced by others. These are the modifications that we call birth and death, the multiple changes of state which any being that has not yet attained liberation or the final transformation (transformation taken here in its etymological sense, that of passing beyond form) must traverse. Attachment to individual things, or to essentially transient and perishable forms, is characteristic of ignorance. Forms are nothing for the being liberated from form, and this is why it is not affected by the properties of the latter, even during its residence in the body.

Thus he moves about free as the wind, for his movements are not impeded by the passions.

When forms are destroyed, the Yogi and all beings enter the allpervading essence.

He is devoid of qualities and actionless; imperishable and without volition; happy, immutable, faceless; eternally free and pure.

He is like ether which is spread everywhere and pervades simultaneously both the inside and the outside of things; he is incorruptible, imperishable; he is the same in all things, pure, undisturbed, formless, immutable.

He is the great Brahma who is eternal, pure, free, one, unceasingly happy, non-dual, existing, perceiving and endless.

Such is the state attained by a being through spiritual knowledge; thus is it forever free from all the conditions of individual existence, and thus liberated from the Empire of the Demiurge.