THE FANTASY CYCLES OF CLARK ASHTON SMITH

PART I: THE AVEROIGNE CHRONICLES

Smith was a one-man literary movement, an alpha and omega unto himself. Although a major early fantasy innovator whom many later writers credit as an influence, he did not begin an ongoing trend in fantasy fiction as some other pioneers did. Contrariwise, he seems to have borrowed his style from almost no one. He was, and is, a unique and unclassifiable talent in the field of fantastic literature. His uniqueness accounts for how little he is published or read today, even though his name always finds its way into discussions of his two compatriots at the pulp magazine Weird Tales, H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. But while they continue to find larger and larger readerships with mainstream editions of their work, Smith has fallen into limbo.

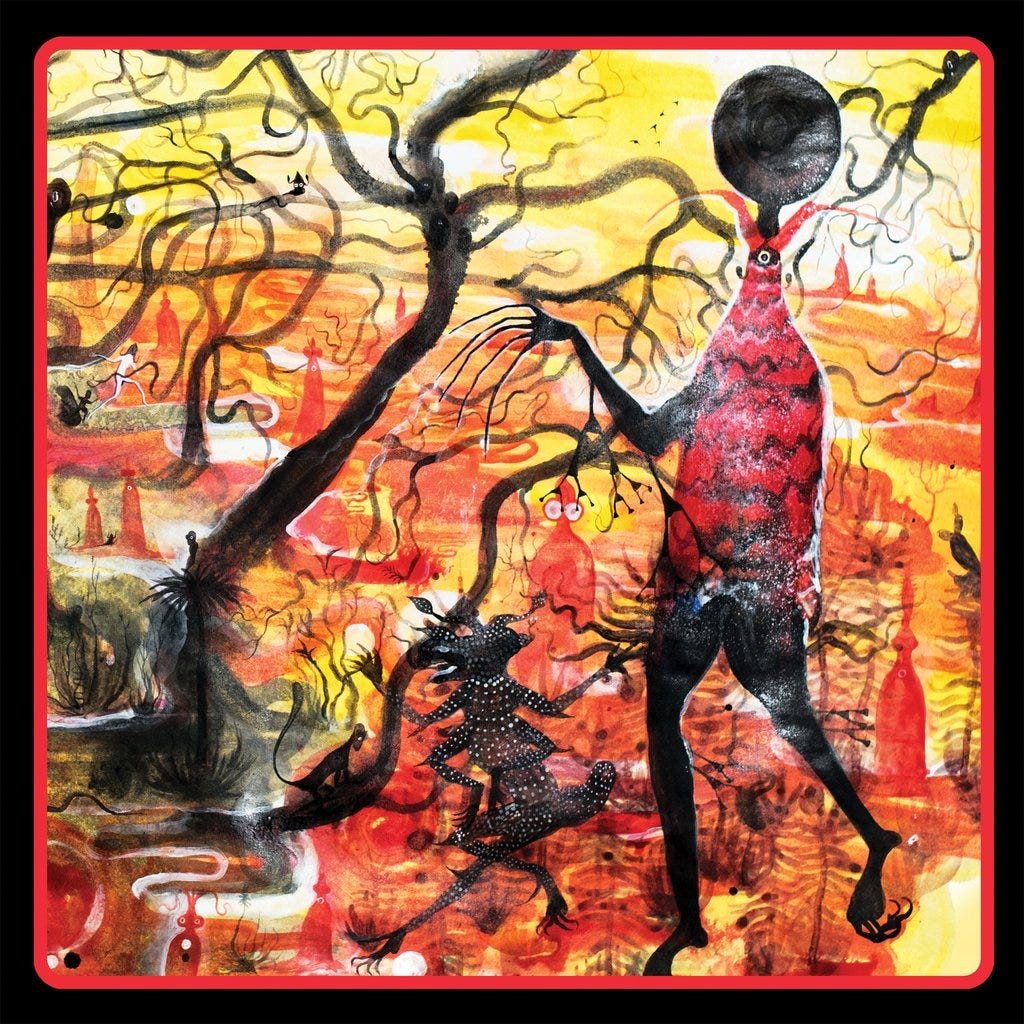

Clark Ashton Smith lived most of his life in Auburn, California, near the foothills of the Sierras in the placer mining region. Today the city of Auburn proudly celebrates its Gold Rush history in its beautifully maintained historic district. But the shade of the city’s greatest artist (not only in prose, but also in poetry, sculpture, and drawing; the illustration above is one of his works) remains elusive. Outside of the historic buildings and the gleaming city hall on its private hill, Auburn is a bland contemporary suburb of Sacramento, filled with traffic jams on the freeway, chain hotels, and strip malls packed with Targets, McDonalds, and Best Buys. Considering that Smith once wrote that “America’s worst enemy is not Bolshevism but its own rank and shameless commercialism,” I have no problem imagining what he might think of his hometown today.

On a visit to Auburn, I tried to dig up as much of Clark Ashton Smith as I could. The library keeps a collection of his rare volumes, the folks who run the used bookstores know a bit about his work, and the small residential street where his house once stood (burned down long ago) now bears his name: ‘Poet Smith.’ But otherwise you could hardly imagine a less congenial setting for a writer whom a recent anthology dubbed ‘The Emperor of Dreams.’

But dreams always transcend their surroundings; that is what makes them dreams. As I lay on my bed in the Auburn Motel 6 during a sweltering late spring evening, listening to teenagers on the street below argue about where they should get their pizza for the night, I flipped through the pages of a collection of Smith’s stories and marveled at the feeling of his prose filtering up from the ground where he spent most of his life. Even surrounded by the dull hum of an air conditioning and the deadening white light of the overhead lamp, and lying on a cheap paisley-pattern comforter, I could read Smith’s words and find myself in lands so removed from the ordinary, so enraptured with the power of language, and so intoxicated with transcendent peculiarity that everything within the reach of my senses vanished and surrendered to Smith’s enchantment.

There is a strange comfort in reading a special author whom you know so few other people have experienced. Ray Bradbury said it best: “Smith always seemed, to me anyway, a special writer for special tastes; his fame was lonely. Whether or nor it will ever be more than lonely, I cannot say. Every writer is special in some way, and those who are more than ordinarily special are either damned or lost along the way.” Knowing that they won’t damn Clark Ashton Smith, and that they are willing to recover what of his might be lost, gives his fans a sense of closeness to him.

However, it still seems tragic that such a talented and influential author should go so unknown today. The modern press, busy getting new books on the shelves to satiate readers who hunger only for fresh material, often lets the precious heritage of older fantasy literature slip away. Although Clark Ashton Smith’s writing will never have widespread appeal because of his ornate style, he should at least have a few paperbacks on the shelves of the local Barnes & Noble.

This series of four essays on the man whom H. P. Lovecraft once jocularly named in mock Egyptian “Klarkash-Ton” represent my contribution to spreading the mysteries of his particular religion: the wonder of words in arcane worlds.

The Word Dervishes of Klarkash-Ton

Clark Ashton Smith considered himself, before all else, a poet. He first made his literary name with his bizarre, cosmic verse. His fiction displays this origin at each opportunity. A poet expresses in concentrated form the resonance of the word and the rhythm of its placement. Likewise, Smith’s stories concentrate on the effect of the weaving of words; plot and character come a distant second in importance. To Smith, words were like the tricks, dips, and pirouettes of a dance routine. For most writers, to move pleasingly to the rhythms of the music of language is a significant achievement. But Smith filled his dances with arabesques, leaps and, jaw-dropping aerials. However, his tricks weren’t merely present to dazzle the audience; they fit with the strange music he had chosen, and their cumulative effect was to create a complete and seamless performance.

His best work does leave a strong emotional residue, but most of that comes from the thick brew of strange words that seem to dwell in the depths of a dictionary that no mortal has ever dared to fathom-except for the esteemed Mr. Smith. He does not tell a story so much as he invites the reader to experience sensations and emotions. The sensations are ancient, sometimes cosmic. The emotions are often unpleasant: decrepit horror, but more often loss and regret.

Because the concept of environment dominates all Clark Ashton Smith’s work, he avoided the use of series characters. Instead of basing his stories around a single protagonist, as Howard and most other pulp writers did, he based them around locations. Three of these fantasy locales formed a large chunk of his output: Zothique, Hyperborea, and Averoigne. In later installments of my survey of Smith’s fantasy works I will examine Zothique and Hyperborea (as well as his ‘mini-cycles’ about Poseidonis, Xiccarph, and Mars), but Averoigne needs the most immediate attention, since it has suffered surprising critical neglect.

Haunted Averoigne: Klarkash-Ton Meets the Real World

Averoigne lies in Southern France. Don’t look for it on any real world maps. It no longer exists, and perhaps never did. It has one major town, the walled city of Vyones, the seat of the Archbishop and home to a magnificent cathedral. The other important towns and villages are Ximes, Perigon, Frenâie, Sainte Zenobie, Moulins, Les Hiboux, and Touraine. The best road in the province travels between Vyones in the north and Ximes in the south. The Abbey of Perigon is the main source of learning, and the Abbot’s library contains an impressive collection of rare tomes. The river Isoile wends through the center of the province and empties out in a marsh to the south. The most important feature of Averoigne is the thick forest that covers most of the center of the province and gives the region its sinister repute. Other places in Averoigne with sorcerous reputations are the ruined castles of Fausseflammes and Ylrougne.

Smith sprinkles details about the province throughout the stories, although the most straightforward portrait appears in “The Maker of Gargoyles”:

At that time, the year of our Lord, 1138, Vyones was the principle town of the province of Averoigne. On two sides the great, shadow-haunted forest, a place of equivocal legends, of loups-garous and phantoms, approached to the very walls and flung its umbrage upon them at early forenoon and evening. On the other sides there lay cultivated fields, and gentle streams that meandered among willows or poplars, and roads that ran through an open plain to the high châteaux of noble lords and to regions beyond Averoigne.

The term ‘haunted’ is applied frequently to the region. For reasons unknown, Averoigne suffers from intrusions of supernatural creatures. Sorcery, although illegal as in all of medieval Europe, lurks in many places, even within the church. The people tolerate a few astrologers and dabblers in the magical arts, but many sorcerers have evil agendas and utilize power described as ‘diabolical’ and hold converse with infernal creatures.

One reason that Averoigne has received less exposure than Hyperborea and Zothique and Smith’s other supernormal creations is its mundane nature. Not only is Averoigne located in real history, it also plays host to already hoary fantasy and horror concepts: vampires, werewolves, spooky forests, time-travel, and witches. Smith’s description of the haunted woods of the province could match any medieval villager’s fearful rumors about his own local forbidding forest:

…the gnarled and immemorial wood possessed an ill-repute among the peasantry. Somewhere in this wood there was the ruinous and haunted Château des Faussesflammes; and, also, there was a double tomb with which the Sieur Hugh du Malinbois and his chatelaine, who were notorious for sorcery in their time, had lain unconsecrated for more than two hundred years. Of these, and their phantoms, there were grisly tales; and there were stories of loup-garous [werewolves] and goblins, of fays and devils and vampires that infested Averoigne. But these tales Gerard had given little heed, considering it improbable that such creatures would fare abroad in open daylight. (“A Rendezvous in Averoigne”)

Compare this to some of Smith’s other fantasy cycles: In Hyperborea an ordinary merchant can have the name Avoosl Wuthoqquan, and a lost solider named Ralibar Vooz can meet a succession of grotesque gods with names like Tsathoggua and Atlach-Nacha. In Zothique, starting your name with two ‘M’s, like Mmatmuor, and raising an army of the dead just for the hell of it aren’t considered unusual. Meanwhile, in Averoigne a man named Gerard gets lost in the woods and meets some vampires. No wonder this medieval French province often drops off the ‘weirdness scale’ that people use to judge the works of Clark Ashton Smith.

In terms of memorable tales, the Averoigne cycle also falls behind Hyperborea et al. Zothique was Smith’s strongest artistic series, while its connections to H. P. Lovecraft’s ‘Mythos’ and its cynical humor have made Hyperborea much more interesting to fans. Averoigne, however, does have a quality other of the author’s stories lack: a familiar setting. When the weird occurs in Averoigne, it has a greater impact because it happens in a realistic, naturalistic environment. Perhaps because of this connection to the real world, Averoigne often features more earthy human emotions, in particular love and its corollary, lust. Romance takes a greater role in the Averoigne stories than it does anywhere else in the Smith canon, and in places a genuine feel of courtly love appears (leavened with doses of lust, of course). “The Enchantress of Sylaire” and “The Holiness of Azédarac” champion love over other forces. On the flip side of romance, lust dominates “The End of the Story,” “The Satyr,” and has hideous repercussions in “The Maker of Gargoyles” and “Mother of Toads.”

Smith also uses the historical setting to engage in religious satire. A number of his other stories, particularly those set in Hyperborea, have satiric-edged humor; but Averoigne provides an actual target: the medieval Catholic Church. The priests of Averoigne come across as an underwhelming force that cannot cope effectively with the horrors and magic of Averoigne. Smith takes pleasure in subjecting the clergy to debauchery and sinister magic that shifts their worldview upside down: “The Colossus of Ylourgne” and “The Disinterment of Venus” take sharp slashes at the clergy’s myopia and helplessness. In one of the most intelligent of the stories, “The Beast of Averoigne,” religion and science meet each other, and religion comes up dangerously short.

The medieval milieu nudges the Averoigne cycle into the familiar realm of heroic fantasy. Smith never wrote pure epic fantasy or sword-and-sorcery, but with stories like “The Colossus of Ylourgne,” “The Holiness of Azédarac,” and “The Enchantress of Sylaire,” he came quite close. Few writers have overtly imitated Smith’s mixture of science/fantasy/horror from his Zothique, Martian, and other planetary tales (Jack Vance excepted), but the werewolf-infested woods and vampire-haunted castles of Averoigne presage countless later dark fantasies set in medieval locations.

Smith completed eleven Averoigne stories, of which all but one appeared in Weird Tales during his lifetime. In the following overview, I have placed the stories in the order that Smith arranged them in his “Black Book,” a chronicle he kept of his short fiction. Smith wanted the Averoigne stories published in book forum as The Averoigne Chronicles, although it is unclear if this is the exact order he wanted them presented (they fall roughly into the order of composition). The only completed story he excluded from the list is “The Enchantress of Sylaire,” which he wrote during a later phase in his career. I have placed it at the end, where I believe the author himself might have slotted it. Smith also included in his list titles for which only synopses exist, and I have placed these at the end of this hypothetical The Averoigne Chronicles as a form of “appendices.”

The Averoigne Chronicles

“The End of the Story”

First published in Weird Tales, May 1930.

Smith nominally dates this story as occurring in 1787, making it the only Averoigne story to take place outside of the Middle Ages or the early Renaissance. However, the historical setting matters little, and nothing distinguishes it from the Averoigne of earlier years.

This first story set the unusual tone for the rest of the Averoigne chronicles: supernatural horror tempered with romance and sexuality, with a few hints of religious satire. Superficially, “The End of the Story” is a horror tale that adheres to a familiar storyline: an antiquarian, in this case a young law student named Christophe Morand, finds a forbidden old volume of lore that tempts him into the clutches of an ancient evil. This plot structure appeared repeatedly in the horror works of M. R. James and H. P. Lovecraft. Yet nothing horrific ever appears before the eyes of narrator Christophe, at least not that he lives to record. For him, this is a love story. The dark hints of what may dwell beneath the Château of Fausseflammes and Abbot Hilaire’s revelation about the true nature of the exquisite lady Nycea are at worst mere annoyances to Christophe and at best an urge to uncover more. Smith’s writing centers on the beautiful, idyllic, and tragically vanished instead of the grotesque; the scenes of Christophe emerging into the illusionary world of Nycea have a Hellenistic exoticism, and Christophe’s attraction to Nycea feels genuine instead of the demonic delusion that the stuffy abbot Hilaire insists it is.

Christophe strives to know ‘the end of the story’ he finds in the forbidden book of the Abbey of Perigon, but ironically we never discover the end of his story-although we can certainly guess it. Smith used a similar device of a man who escapes a horrible fate, only to find himself willfully driven into its clutches again — with unseen results — in his Martian story, “The Vault of the Yoh-Vombis.” Lovecraft’s “The Shadow over Innsmouth” has a similar reversal coda.

This is the only place in the Averoigne cycle where the clergy appears to wield any power against supernatural evil. Smith later portrays priests, monks, and bishops as either helpless aesthetes who turn every problem over to God, or else as cynical co-conspirators with dark forces. Abbot Hilaire successfully repels a vampire with holy water, but in “The Colossus of Ylourgne” demonic figures actually seize sacred implements and beat the monks with them in a mocking turnabout. Although the Averoigne stories use Judeo-Christian epithets for evil forces, Smith gives no proof of the existence of supreme deities of either good or evil.

“The Satyr”

First published in Genius Loci (Arkham House, 1948)

This is the shortest of the Averoigne chronicles and never appeared in the pages of Weird Tales, probably because of the hints of carnal lust and sexuality that underlie the appearance of a lecherous Pan-like figure and a forest with ‘obscene’ shapes that ignites passionate feelings between a pair of adulterous lovers. The Arthur Machen novella The Great God Pan and short story “The White People” may have influenced Smith, but his story again has the aura of courtly romance that clings peculiarly to Averoigne, and therefore a sense of genuine horror never blooms. The touches of genuine romance between the couple are the spark of this otherwise simple and quick fable.

Smith wrote an alternate ending to the story with a gruesome and even more sexual outcome. He cut it, perhaps, to make it more saleable (and apparently failed). The variant conclusion reads marginally better, since it combines the sex and violence inherent in the nature of Pan.

“A Rendezvous in Averoigne”

First published in Weird Tales, April/May 1931

This story bequeathed its name to a 1988 Arkham House collection of Smith’s stories and has seen more reprints than any of the other Averoigne tales, most likely because it deals with a standard monster with which most readers are familiar: the vampire. The traditional medieval European backdrop of Averoigne allowed Smith to utilize the customary monsters of fable more than in his more supermundane settings: aside from vampires, satyrs, gargoyles, and werewolves all make appearances. Fans of the writer’s stranger inventions might find this story too familiar and simplistic, but the magic of his prose still weaves an ensnaring web around the standard plotting.

A romantic tryst provides the catalyst to lure a troubadour named Gerard into the forest of Averoigne and to a mysterious castle. The castle’s tenants, Sieur de Malinbois and his chatelaine Agathe, heap hospitality on Gerard, his lover Fleurette, and her two servants, but a dim memory of the legend of two foul long-dead sorcerers with similar names makes Gerard believe that his hosts have something malign planned. The rest of the tale resorts to the vampire cliches of red marks on necks, a hidden tomb, a stake in the heart, and waving holy objects. Stylistically however, this is one of the most beautifully readable of the stories, walking the border between the lighthearted romantic ambitions of Gerard to rescue his beloved Fleurette and the eerie depiction of the mysterious castle of Sieur de Malinbois, where flames are still as “tapers that burn for the dead in a windless vault,” and from the stifling air creeps “forth a mustiness of hidden vaults and embalmed centurial corruption.”

“The Maker of Gargoyles”

First published in Weird Tales, August 1932

In Averoigne there’s love, and then there’s lust. “The Maker of Gargoyles” has a surprising amount of the latter for a Weird Tales story, considering the truncation of Smith’s later “Mother of Toads” and editor Farnsworth Wright’s dislike of Robert E. Howard’s rapine-minded “The Frost Giant’s Daughter.” Taking psychoanalysis into his mythical region of France, Smith turns the hatred and lust of an unpleasant stonemason in the city of Vyones into two stone gargoyles that come to life and terrorize the population at night. Readers can take it as a straightforward horror story about a man who gets his comeuppance from his own creations, but the sexual content — again described in ‘saturnine’ and ‘satyr’ terms — makes it stand out. Smith also maintains good suspense in the finale.

“The Holiness of Azédarac”

First published in Weird Tales, November 1933

This story has more humor than usual for a Smith’s prose (outside of the sardonic comedy of the Hyperborea series). He takes many satiric jabs, mostly at religion, but also at himself and his fellow correspondent from Weird Tales. Villain Azédarac is a comic sorcerer who rants about his devilish contacts like a name-dropper at a Hollywood party. The first few pages contain a cornucopia of weird gods, some borrowed from Lovecraft and Howard: “By the Ram with a Thousand Ewes! By the tail of Dagon and the Horns of Derecto!” On that note, the rest of the story reads something like a high romantic lark, and along with “The Enchantress of Sylaire” is the cheeriest of the stories; indeed, it ranks as one of brightest pieces that Smith wrote, overcoming his customary pessimism. He suggests that love is the ultimate retreat, even when all else fails, and all the crimes of horrible men mean nothing when you have a pair of loving and lusting arms wrapped around you.

The story takes a non-science-fiction approach to time travel. Azédarac, Bishop of Ximes and a diabolical sorcerer who has covered up his demonic rituals for years, uses his magic to send the monk who can expose his activities backwards in time seven hundred years to 475 C.E. There the poor monk finds unexpected help — and even more unexpected romance — from a pagan sorceress. This plot contains tropes appropriate to heroic fantasy: An evil sorcerer sends an assassin to get rid of a spy, a band of pagans tries to sacrifice the hero, there’s a scene in a rough-and-tumble tavern, and the heroine is a bewitching sorceress. Smith clearly takes the side of paganism and its unbridled sexuality over the strict mores of medieval Catholicism. The story’s sarcastic title and the character of Azédarac are also satiric shots at the church. Azédarac mostly serves a comic purpose. He rants ridiculously with a froth of demonic names bubbling from his lips, but he seems more like a low-level office bureaucrat who’s afraid his manager will discover he has started embezzling from the company picnic fund. Compare him to the sorcerer Nathaire in “The Colossus of Ylourgne,” whom Smith portrays with maximum menace and minimum irony.

“The Colossus of Ylourgne”

First published in Weird Tales, June 1933

This novelette is among the longest works that Smith published, running over 14,000 words, and in it the author achieves a near masterful epic of dark fantasy. Grisly images of necromancy, tomb-born terror, and gruesome destruction appear throughout, but instead of Grand Guignol horror, the end result is a heroic fantasy adventure — and close to sword-and-sorcery in the modern sense. If hero Gaspard du Nord, one of the few examples of a truly heroic character in Smith’s fiction, had picked up a sword at some point, “The Colossus of Ylourgne” would immediately qualify as sword-and-sorcery. There are striking similarities between it and Robert E. Howard’s then-emerging fantasy stories taking place in mythic pre-histories. The mix of Smith’s dark word magic with the heroic adventure make this one of his prose masterpieces and the jewel in the crown of Averoigne.

Given the longer length of the piece, Smith weaves a more intricate plot than usual and uses the template of a hero going against an evil sorcerer with a super-villain scheme. In 1281, the ailing necromancer Nathaire flees from the city of Vyones and plots ghastly vengeance from the ruined castle of Ylourgne before he dies. Gaspard du Nord, Nathaire’s former disciple, learns from his visitation to Ylourgne that Nathaire has summoned fresh corpses from all over Averoigne to serve as raw material for the making of a one hundred foot-tall dead body into which he will transfer his spirit…and then flatten all of Averoigne. It falls on du Nord to find a way to stop him.

Smith has more going on here than an exciting adventure and the lure of necromantic imagery (in which he indulges with delightful gluttony). The religious satire that weaves through the Averoigne cycle reaches its apotheosis here. Nathaire, in the form of the Colossus, vents his anger predominantly against the clergy and their icons, who can do nothing but pray hopelessly or flee. The Colossus looms as a titanic blasphemy that holds dominance over the symbols of Christianity, and it only falls to the forces of another wielder of forbidden magic, who ironically posts himself on the top of the Cathedral of Vyones to face his adversary.

“The Colossus of Ylourgne” also contains a rare mention of the events in another story. Gaspard du Nord, while climbing up into Vyones Cathedral, hides behind a gargoyle with features identical to the lustful stone carving that tormented the city over a hundred and fifty years ago in “The Maker of Gargoyles.”

“The Mandrakes”

First published in Weird Tales, February 1933

From the epic tale of the Colossus, Smith dives down to the simple fable of “The Mandrakes,” which resembles Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Black Cat.” It’s a short and unremarkable story about a sorcerer specializing in love potions who murders his wife and finds strangely feminine-shaped mandrakes growing over her hidden grave. Even Smith’s trademark writing style feels stale and underused, but the link between lust and violence and the theme of the souring of love are further examples of the earthy opportunities that the Averoigne setting offered to the writer.

“The Beast of Averoigne”

Shorter version first published in Weird Tales, May 1933

Science fiction lands in Averoigne. Smith takes the alien invasion plot and drops it into the Middle Ages, where religion has no ability to comprehend it except in hoary diabolical terms and can do nothing against it. Only a budding scientist — still cursed with the terms “sorcerer” and “astrologer” — can hope to achieve anything. The similarities to “The Colossus of Ylourgne” show up immediately, but “The Beast of Averoigne” places itself more firmly in the science-fiction realm. Smith also experiments with a three-part narrative that might have taken inspiration from H. P. Lovecraft’s similarly divided “The Call of Cthulhu.”

Three different documents tell the story of coming of the baleful Beast of Averoigne in the year 1369. Gerome, a monk of the abbey of Perigon (already explored twice in previous stories), writes an account of his first meeting with the bizarre, snake-like creature that appears in conjunction with a comet in the sky and begins a reign of terror. A letter from the Abbot of Perigon, Theophile, to his niece in a convent relates the further depredations of the creature across the countryside; the Abbot voices his own doubts about his mind. Finally, the sorcerer-astrologer Luc Le Chaudronnier writes a statement about his effort to kill the Beast — which he has come to recognize is a creature not from the Earth — with the power of Ring of Eibon, a artifact which (Smith hints) contains another extraterrestrial entity of great power.

At the finale, Luc le Chaudronnier comes close to a true understanding of the identity of the Beast of Averoigne when he breaks free from the bond of the terrestrial thinking and its conception of religious good and evil:

Indeed, it were well that none should believe [this] story: for strange abominations pass evermore between earth and moon and athwart the galaxies; and the gulf is haunted by that which it were madness for men to know. Unnameable things have come to us in alien horror, and shall come again. And the evil of the stars is not as the evil of the earth.

The story cannot match “The Colossus of Ylourgne” in excitement, but the flawless use of three medieval voices and the fascinating collision between science and religion make this one of the most intriguing of the Averoigne chronicles.

Two version of the story exist. After Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales rejected the original, Smith shortened it and dropped the triptych style, making the entire story the account of Luc Le Chaudronnier and integrating the earlier events into his testimony. The strongest elements of the original remain, but some of the complexity and vanishes. The loss of the individual voice of Abbot Theophile in his letter to his sister takes away the specter of personal tragedy. However, comparing the two versions does give an interesting picture of Smith’s revision process and which elements he chose to highlight and which to discard.

“The Disinterment of Venus”

First published in Weird Tales, July 1934

This brief tale about the monks of Perigon (yes, them again) exhuming a lewd statue of Venus misses a number of opportunities for lusty, erotic satire, but Smith cannot take the blame for it: more explicit material would never have made it into print in the 1930s. That still cannot keep the reader from wondering what Smith could have done with the lustier elements if he had written them today, in the age of Anne Rice. The concept of an austere monastery falling into lecherous debauchery because of an erotic statue conjures up comic and horrific possibilities, but Smith can realize none of them under the publishing restraints of the time. A few of the monks spend a night drinking in a tavern, and that marks the limits of their carousing. Smith also plays briefly with the notion that the uncovered Venus represents not the classical goddess, but her earthier ‘chthonic’ form — the darker and bawdier part of Greek religion that rarely gets taught in high school.

“Mother of Toads”

First published in Weird Tales, July 1938, in an expurgated version.

Smith occasionally wrote gruesome and nauseous horror stories that prey on the readers’ senses. “The Mother of Toads,” like the similar freakish “The Seed from the Sepulchre,” works on a primarily revolting level. It’s the least likable of the Averoigne stories, but Smith’s ability to repulse is quite astonishing. It raises the lust theme of the Averoigne cycle to new heights: lust as a sickening, smothering murderer. It is no surprise that Weird Tales forced Smith to gut the story of its salacious and nasty sexual passages before it appeared in the magazine four years after he originally wrote it.

Mere Antoinette, a grotesque witch who lives in the southern swamps, seduces the young messenger-boy Pierre with one of her potions. The lascivious descriptions of the enchantment and lovemaking (slashed entirely from the Weird Tales version) have a slimy repugnance that equals anything Smith wrote:

This time he did not draw away but met her with hot, questing hands when she pressed heavily against him. Her limbs were cool and moist; her breasts yielded like the turf-mounds above a bog. Her body was white and wholly hairless; but here and there he found curious roughness…like those on the skin of a toad…that somehow sharpened his desire instead of repelling it.

She was so huge that his fingers barely joined behind her. His two hands, together, were equal only to the cupping of a single breast….The couch was rude and bare. But the flesh of the sorceress was like deep, luxurious cushions…

Mere Antoinette’s hideous revenge against Pierre’s eventual rejection of her feels tame compared to the descriptions of their amorous encounters!

But buried in this squeamish tale of magic-induced lewdness is a morsel of regret. Mere Antoinette, for all her repulsive physical characteristics, only wants the male attraction she knows she can never attain legitimately. Even though readers understand Pierre’s horror and denial of her, that cannot keep them from sympathizing with the ‘Mother of Toads’ in her loneliness.

“The Enchantress of Sylaire”

First published in Weird Tales, July 1941

Clark Ashton Smith abruptly stopped writing fiction in 1935 after completing what he conceived of as his final Zothique tale, “The Last Hieroglyph.” He did periodically return to short fiction for the rest of his life (he died in 1961), and wrote additional stories both of Zothique and Hyperborea. But he wrote only one further entry in the Averoigne chronicles: this charming fantasy that crosses the borders of fairytale and sword-and-sorcery. At the end of the stories of Averoigne, love conquerors all, and a hero even draws a sword to defend his love against a slavering monster.

Young dreamer Anselme, with his devotion to beauty and books and romance, might stand for Clark Ashton Smith himself, or at least for many of his readers:

He seated himself on one of the boulders, musing on the strange happiness that had entered his life so unexpectedly. It was like one of the old romances, the tales of glamor and fantasy, that he had loved to read. Smiling, he remembered the gibes with which Dorothee des Flèches had expressed her disapproval of his taste for such reading-matter. What, he wondered, would Dorothee think now?

Anselme, after the pretty but haughty Dorothee rejects him, stumbles into the faery region of Sylaire and its lovely sorceress Sephora. The smitten Anselme helps Sephora defeat the werewolf Malachie du Marais, and at the end it is Anselme who must reject Dorothee for the true love of Sephora. The courtly romance is startling for Smith, as is the aspect of heroic fantasy, but a genuine optimism infuses the story and makes it the most likable of all the Averoigne chronicles and a fitting end for the cycle — whether Smith intended it as the last story or not. The final sentence is one of the most optimistic and romantic that the author ever wrote.

Fragments and Synopses

These eleven stories are the only completed works of Averoigne, but Smith kept extensive notes for others in his “Black Book.” Titles and synopses for other chronicles in the haunted French province survive: “The Sorceress of Averoigne,” “Queen of the Sabbat,” a sequel to “The Holiness of Azédarac” called “The Doom of Azédarac,” “The Oracle of Sadoqua,” and “The Werewolf of Averoigne.” The titles alone can quicken the heart of any reader of Clark Ashton Smith and give glimpses of the further wonders that might have emerged.

One of the synopses, “The Doom of Azédarac,” shows that Smith planned to further explore science-fiction concepts in Averoigne. The evil sorcerer-bishop Azédarac, on the verge of death, transports himself across dimensions to an alternate Averoigne and battles a version of himself in a duel. This story would have pushed the Averoigne cycle into the realms of hypothetical contemporary science.

The other intriguing synopsis that survives is “The Oracle of Sadoqua.” The outline takes place during the Roman occupation of Gaul, when Averoigne is known as “Averonia.” A Roman officer, Horatius, searches for his lost friend Galbius and finds him in a cave where the vapors of the breath of the pagan god Sadoqua (possibly a reference to the toad-god entity Tsathoggua in the Hyperborea stories) slowly devolve him into a hideous beast. Horatius also has an encounter with a beautiful pagan girl, indicating that Smith planned to also explore the romantic/erotic aspect of Averoigne in the story. The strong potential of a lengthy story early in Averoigne’s history, possibly explaining the origin of the weirdness of the region and containing doses of Lovecraftian horror, makes this another unfortunate case of an idea never coming to fruition.

Postscript

The complete Averoigne stories do not necessarily show Clark Ashton Smith at his bizarre best, and stories like “The Mandrakes” and “The Disinterment of Venus” will never rank as more than minor works. However, Averoigne’s conception as an historical environment makes it one of the most intriguing of Smith’s settings. And, perhaps, the one that would have worked the best if he had written it today. The stories show an earthy eroticism that begs to be cut loose from the censored constraints of the 1930s. In the erotic fantasy and dark horror market of today, Averoigne would make an ideal setting. The shadows of religious satire could also broaden in the modern writing scene. Perhaps the seeds of Averoigne were planted too early to flower properly.

Of course, fans of Klarkash-Ton might find it tempting to travel to Averoigne and create their own stories. I, myself, have often wondered about the succubi that Smith often mentions, and I have felt the sorcerous enchantment of the werewolf-haunted forests luring me to set my pen to paper and bring Averoigne back from the dusty parchments of the library of the Abbot of Perigon….

THE FANTASY CYCLES OF CLARK ASHTON SMITH PART II: THE BOOK OF HYPERBOREA

Legend says that after his exile from Iceland, Erik the Red voyaged to a frozen island and settled there in 982 C.E. Deciding not to scare away new settlers with an intimidating name like “Iceland,” he dubbed the place “Greenland.” We can scoff at Erik’s bit of dishonesty-in-advertising, and certainly any homesteaders who fell for his marketing ploy would have felt like cleaving Mr. The Red’s skull with a scramasax, but perhaps Erik knew something about Greenland’s deeper history: the lost chronicles that fantasy writer Clark Ashton Smith revealed in his stories about a far northern continent in its younger days before glaciers claimed it, when wizards and elder gods and wily thieves and greedy moneylenders crisscrossed its steamy jungles and ebony mountains and opulent cities. A vanished civilization known as…Hyperborea.

Of Clark Ashton Smith’s three major fantasy series, Hyperborea had the worst sales record during his lifetime. Smith finished ten stories about the ancient continent, and most bounced back and forth from various magazines until they finally found homes. The majority ended up in Farnsworth Wright’s Weird Tales (sometimes after multiple tries), but others landed in ephemeral pulps or non-paying fanzines.

Reading the Hyperborean stories today it is easy to understand why Clark Ashton Smith had such a burdensome time selling them: nowhere else in his canon does he so artificially elevate his prose style. Although the stories of Zothique swim in decadent and decaying imagery, Hyperborea drowns in sententious language that Smith uses for ironic effect. “The Coming of the White Worm” might rank as the most obtusely written of all his stories, and it only saw print after Smith considerably simplified the language.

Posthumously, Hyperborea has gained stature among Smith’s works, and the stories appear frequently in anthologies. The continued popularity of the Hyperborea stories today comes from two factors: their links to H. P. Lovecraft’s famous “Mythos,” and their doses of grotesque ironic humor.

Situating Hyperborea

Exactly what, where, and when is Hyperborea?

The concept originates with the Greeks; the word means “beyond the north wind.” Herodotus mentions Hyperborea as a land far to the north of mainland Greece, filled with joyous people who lived an Elysian existence under warm twenty-four hour sunshine. In some versions of the myth of Perseus, the hero seeks for the Gorgons after passing the land of the Hyperboreans.

Smith includes little of this Grecian concept of Hyperborea except that of a northern land existing in a warm state, and borrows more from modern theories about the land. In the traditions of later literature, Hyperborea thrived coeval with the other mythic civilizations of Atlantis, Lemuria, and Mu (which all receive mention in Smith’s stories) that Helena Blavatsky promoted in Theosophy, a pan-religious gnostic movement she founded in 1875. Smith acknowledged his debt to Blavatsky’s bizarre occultism:

Theosophy, as far as I can gather, is a version of esoteric Yoga prepared for western consumption, so I dare say its legendry must have some sort of basis in Oriental records. One can disregard the theosophy, and make good use of the stuff about elder continents, etc. I got my own ideas about Hyperborea, Poseidonis, etc. from such sources, and turned my imagination loose. (Letter to H. P. Lovecraft, 1 May 1933)

In “Ubbo-Sathla,” Smith states that Hyperborea was “supposed to have corresponded roughly with modern Greenland, which had formerly been joined as a peninsula to the main continent.” The setting and geography agree with this assessment: unlike the other lost civilizations of Lemuria, Mu, and Atlantis, Hyperborea did not sink from sight but vanished under an advance of ice. It seems logical that the land mass still exists, and the glacier-covered island of Greenland, large enough to almost qualify as a continent, fills the Hyperborean bill.

Smith mentions that the stories occur “in the last centuries before the onset of the Great Ice Age,” possibly meaning the last long interglacial period, the Eemian Interglacial (130,000-70,000 B.P.). The mention of mammals common to this epoch, such as saber-tooth cats, aurochs, and mammoths, further places the period as the recent Pleistocene, before the start of human civilization. However, in “Ubbo-Sathla,” Smith gives a different period in Earth’s history for Hyperborea: the Miocene Period, approximately twenty-three million years past, which concluded in a glacial advance. Dinosaurs, such as a Tyrannosaurus and an Archaeopteryx, appear in “The Seven Geases” alongside mentions of saber-tooth tigers and mammoths. With so many contradictions, it seems that locating Hyperborea in time serves little purpose. It exists in a nebulous past outside of our own understanding of time.

The ten stories and other references in Smith’s fiction and letters provide enough information to craft a general overview of Hyperborea’s geography and history. In this warm interglacial period, thick moist jungles coat much of the middle of the continent. The black range of the Eiglophian Mountains cuts through the middle of the land and lies a day’s march from the two capital cities, Commoriom and Uzuldaroum. Most of the foulest deities of Hyperborea live in caverns beneath the tallest of the Eiglophians, Mt. Voormithadreth. The citizens abandoned the older capital Commoriom, “superb and magisterial…opulent among cities,” during the reign of King Loquamethros because of the prophecy of the White Sybil of Polarion. The fleeing population established a second capital only a few leagues away, Uzuldaroum. The northernmost peninsula is Mhu Thulan (derived from the Latin “Ultima Thule”), where the wizard Eibon dwells in his pentagonal tower. The largest city in Mhu Thulan is Cerngoth. Another important city, Iqqua, which has its own line of kings, lies close to Mhu Thulan. Above Mhu Thulan looms the icy waste of the enormous glacier of Polarion. Eventually, as the White Sybil augured, the glacier of Polarion destroys Hyperborea and leaves behind the land we know as Greenland. Only the stories of the prophet Klarkash-Ton survive to tell us of the vanished wonders of Hyperborea.

The Clark Ashton “Smythos”

The Hyperborean cycle constitutes Clark Ashton Smith’s largest contribution to what August Derleth later termed “The Cthulhu Mythos” (referred to here simply as “The Mythos”), H. P. Lovecraft’s loose pantheon of star-born primordial gods and their influence on earth.

Lovecraft, one of the most popular scribes of Weird Tales and the most celebrated horror author of the last century, started an industry of terror when he published “The Call of Cthulhu” in 1926. This story of a reawakening cosmic evil that causes a scholar to reassess the rationality of existence had a tremendous effect on the horror field. Lovecraft maintained a voluminous correspondence with other authors in which they swapped ideas and concepts that tied in with Lovecraft’s gradually growing cabal of garbled-named gods and fictional tomes of mind-searing lore. Long after Lovecraft’s passing in 1937, other writers would continue to pour out new pastiches of his “Mythos,” creating a strange and misunderstood horror sub-genre.

But Clark Ashton Smith’s expeditions into the Mythos were not pastiches like those of August Derleth or the young Ramsey Campbell. His take on the Mythos is so uniquely his, that a few have jokingly called it the ‘Clark Ashton Smythos.’ The cosmic Old Ones that appear so distant and incomprehensible in Lovecraft’s work and those of his imitators take on the mantle of cruel, capricious jesters in Smith’s renditions. Will Murray notes that “Smith’s Old Ones were more in the nature of the Greek Gods, meddling in human affairs and concerns despite their often outlandish names and semi-anthropomorphic forms, and issuing pronouncements in human tongue.” The Greek pantheon connection works for the more humorous of the Hyperborean stories, but there is also a link to the grim gods of the Norsemen, particularly in a subset of the stories about the slow death of Hyperborea beneath the advancing glaciers, where the ironic humor of the series nearly vanishes. Either way, Smith’s cosmic terrors have a direct presence in his stories as characters in a way that Lovecraft’s never do.

Smith’s most important additions to the Mythos first appeared in Hyperborea: the tome of lore known as The Book of Eibon (Livre Ivonis in its French translation), and the toad god Tsathoggua. Tsathoggua runs through the Hyperborean stories as a common motif and sets the ironic-comic tone for much of the cycle. The toad god shows how far Smith’s vision of the Mythos veers from Lovecraft’s. In “The Door to Saturn,” Smith gives Tsathoggua a typical Lovecraftian background: he drifted down from the stars in forgotten eons (using Saturn as a ‘way-station’) and established himself deep underground on earth in pre-human days, eventually cultivating slavish followers. However, in “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros,” Smith gives a physical portrait of Tsathoggua quite unlike Lovecraft’s cosmic, mind-blasting terrors:

He was very squat and pot-bellied, his head was more like that of a monstrous toad than a deity, and his whole body was covered with an imitation of short fur, giving somehow a vague suggestion of both the bat and the sloth. His sleepy lids were half-lowered over his globular eyes; and the tip of a queer tongue issued from his fat mouth. In truth, he was not a comely or personable sort of god….

In Tsathoggua’s portraiture lurks something clownish and grotesquely funny. This dark-comic feeling fits the Hyperborean cycle, and the ironic final phrase might sum up the dry sarcasm of much of the series.

(Smith apparently had an affinity for the toad god. In a 1934 letter to Richard Searight, he wrote: “Tsathoggua is one of my specialties!”)

Clark Ashton Smith scholars have often overstated the humorous aspect of Hyperborea and let it color their perceptions of the series. Not all the stories contain black comedy and sarcastic language as in “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros” or the bizarre “The Seven Geases.” Three of the stories form a sub-cycle about Hyperborea’s doom, and Smith wrote them close together. In these stories he leans toward the crepuscular tone of his popular Zothique series, which started to emerge while he was deep in the Hyperborean stories. Additionally, the work “Ubbo-Sathla” stands outside the rest of the series in tone and setting, and reads like an homage to Lovecraft’s style. Sardonic comedy plays a large part in Hyperborea’s appeal, but many more levels lay beneath its thin coating of ice.

The Book of Hyperborea

Smith planned to collect the stories of Hyperborea into a single volume with the hope of finding a publisher. He called the proposed collection The Book of Hyperborea, the name that Necronomicon Press used for its 1996 anthology. I have chosen to list the stories in the order of their composition, instead of the chronological order that Lin Carter devised for his Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series or the version that Smith listed in his Black Book because the development of the series appears more obvious in this arrangement.

“The Tale of Satampra Zeiros”

Completed November 1929. First published in Weird Tales, November 1931.

This first-person narrative, the work of thief and raconteur Satampra Zeiros, sets the tone for the bizarre stories that follow. Our penurious narrator embellishes his brief horror story about an unfortunate looting expedition with such pompous language that it makes the horrific incident into a sarcastic joke-almost. The terror aspect peeps through just enough, and structurally the narrative follows a familiar horror outline. But the joy of the story comes from the way that Smith flips the situation upside-down with Satampra Zeiros’ language that distances him from not only the terror of the action, but also from his career as a thief and drunk.

When Satampra Zeiros and his companion in crime Tirouv Ompallios encounter a hideous guardian in the temple of the toad god in the ruined old capital of Commoriom, he mentions that the creature gave “evidence of anthropophagic inclinations” and therefore their “departure” became “most imperative.” This is the way an unreliable narrator tells you that he saw a man-eating monster and got the hell out of there.

Satampra Zeiros himself achieved a rare distinction among Smith’s characters: he came back for a sequel. The one-handed thief would again tell of his adventures in the last Hyperborean story, “The Theft of the Thirty-Nine Girdles.”

“The Door to Saturn”

Completed July 1930. First published in Strange Tales, January 1932.

Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright rejected this, one of the most bizarre of all Hyperborea stories, but Smith found a home for it in Clayton Publications’ better paying (but short-lived) rival, Strange Tales. The story must have caused some Wright real head-scratching; “Satampra Zeiros” contains ironic humor but still tells a conventional horror story. The “The Door to Saturn,” however, is a lengthy ‘punch line’ piece filled with comic-tinged oddness and jaw-busting alien names. It has more in common with the satirical fantasies of James Branch Cabell than anything that appeared in Weird Tales.

Very little of the story takes place in Hyperborea proper, but instead on the planet Cykranosh. The reader meets for the first time the frequently referenced sorcerer Eibon, who worships and receives favor from Tsathoggua (here spelled Zhothaqqua). When the inquisition of the elk-goddess Yhoundeh comes to seize Eibon for his heresies in his tower in far northern Mhu Thulan, the sorcerer escapes through a panel that takes him to Cykranosh, the planet where Tsathoggua once dwelt. The high priest of Yhoundeh, Morghi, follows after Eibon, and the two enemies team-up to survive among the weird peoples of Cykranosh while Morghi seeks to deliver a sacred phrase he learned from one of Tsathoggua’s ‘relatives.’ Ultimately, the set-up exists to deliver a twist finale that mocks the pretensions of religious quests. Smith would repeat this ‘set-up/punch line’ structure again in the even more effective “The Seven Geases.”

As the story’s title makes clear, Cykranosh is nominally Saturn. But the world on which Eibon and Morghi find themselves has more in common with H. G. Wells’ fantastic vision of life on the moon in The First Men in the Moon, Frank L. Baum’s Oz, and the setting of Bob Clampett’s surreal animated short “Porky in Wackyland.” The list of alien creatures comes with knowing, eye-winking ludicrousness.

“The Testament of Athammaus”

Completed February 1931. First published in Weird Tales, October 1932.

Through another first-person account, this one from Athammaus, head executioner of the capital of Hyperborea, we hear about a central event in the history of the continent: the sudden abandonment of the capital Commoriom. When the execution of highwayman Knygathin Zhaum goes strangely wrong, the bizarre killer’s old ancestry to Tsathoggua starts to manifest itself. One execution after another cannot keep Knygathin Zhaum dead, and all of Commoriom soon suffers from the condemned man’s disturbing transformation.

The mordant humor of much of the Hyperborean cycle ebbs lower in this story. Athammaus does not have Satampra Zeiros’ picaresque sense of irony, but the hideous situation does have an absurd comedy to it, and Athammaus’ pride in his skills as an executioner make for amusing comments about the one execution that simply will not go the way it should. However, “The Testament of Athammaus” works mostly as horror, and Smith’s ornate writing reaches superb heights as Knygathin Zhaum turns less and less human; Smith visualizes the serpentine and mottled appearance of the creature, even in its more anthropoid stage, with loathsome delight. In a letter to H. P. Lovecraft in 1931, he expressed his satisfaction with the story, and commented that he thought Knygathin Zhaum was his best monster yet. But it still took two tries to get the story into Weird Tales, and it has seen few reprints since despite its quality and centrality to Hyperborean history.

“The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan”

Completed November 1931. First published in Weird Tales, June 1932.

This is the only Hyperborean story that Farnsworth Wright bought for Weird Tales on first submission. Smith himself had no great love for it, calling it “filler,” and it served as back-page material in the magazine. However, it has seen multiple reprints, probably because, as the shortest of the stories in the cycle, it fits easily into anthologies.

The story falls in a horror subcategory familiar to readers of E. C. Comics’ Tales from the Crypt or anthology television shows: a hateful, unlikable individual gets a gruesome but appropriate comeuppance. Greedy money-lender Avoosl Wuthoqquan of Commoriom receives a curse from a beggar, and the curse comes true when Avoosl Wuthoqquan’s avaricious pursuit of two magical gems leads him into the lair of a Tsathoggua-esque monster with a snide sense of humor. There is little else to the story, which has an adequate amount of strange descriptions and sly irony (particularly in the matter-of-fact final sentence), but nothing otherwise noteworthy or memorable.

The title requires an explanation for modern readers. “Weird” used as a noun has no connection to the adjective meaning ‘strange.’ It derives from the Old English and Scandinavian word wyrd or werde, meaning fate or destiny. An author less interested in painting a picture of an archaic world would have named the story “The Strange Fate of the Money-Lender.”

“Ubbo-Sathla”

Completed February 1932. First published in Weird Tales, July 1933.

In his “Black Book,” where he kept a record of his writings, Clark Ashton Smith listed this story as part of The Book of Hyperborea, even though it only marginally touches on the ancient continent and begins and ends in contemporary London. It also contains none of the humor of the Hyperborean stories; Smith attempts to duplicate the style and structure of H. P. Lovecraft, and succeeds. Like many of Lovecraft’s stories, the protagonist of “Ubbo-Sathla” is an antiquarian on a quest for greater occult knowledge. He stumbles upon something ‘Man Was Not Meant to Know,’ and his fate remains nebulous in an epilogue tacked on the end. The short piece may fit poorly with the rest of the Hyperborean cycle, but “Ubbo-Sathla” makes for a first-rate Clark Ashton Smith plunge into the primordial.

The antiquarian in this case is Paul Tregardis, anthropology student and occult enthusiast, who has obtained a copy of the French translation of The Book of Eibon. In a curio shop in London he finds a mysterious rock unearthed in Greenland and believes he has located the magic stone that Hyperborean sorcerer Zon Mezzalamech used to peer back into the beginnings of earth to discover tablets of wisdom. Like a Lovecraft character, Paul Tregardis feels a fateful pull to stare into the stone and repeat the magic of Zon Mezzalamech to see back to the ultimate beginning and behold Ubbo-Sathla, the source of all terrestrial life.

Ubbo-Sathla, a primal bio-blob from which all other life eventually splits away and evolves, is another of Clark Ashton Smith’s important contributions to the Mythos. Ironically, Smith’s conception of Ubbo-Sathla does not deviate far from what some biologists now theorize about the origins of life on our planet. But where a scientist would marvel at the wonder of such a primordial creature, both author and character behold it with horror:

There, in the grey beginning of Earth, the formless mass that was Ubbo-Sathla reposed amid the slime and the vapors. Headless, without organs or members, it sloughed from its oozy sides, in a slow, ceaseless wave, the amoebic forms that were the archetypes of earthly life. Horrible it was, if there had been aught to apprehend the horror; and loathsome, if there had been any to feel loathing. About it, prone or tilted in the mire, there lay the mighty tablets of star-quarried stone that were writ with the inconceivable wisdom of the pre-mundane gods.

Here Clark Ashton Smith gambols in the black fields of H. P. Lovecraft, turning the old supernatural horrors into something cosmic, scientific, and yet even less comprehensible and dreadful than before.

“The Ice Demon”

Completed July 1932. First published in Weird Tales, April 1933.

The three “Ice Doom” stories, following close upon each other, bring the reader toward the eventual doom of Hyperborea beneath the advancing glaciers. This mini-cycle differs from the rest of the series: humorless and seeming to imitate Smith’s two other fantasy worlds, Averoigne and Zothique.

“The Ice Demon” probably occurs chronologically last in the series. The glacier of Polarion has pushed far south over the continent, crushing out all of Mhu Thulan. The King of the Northern city of Iqqua vanishes with his wizard when they try to halt the marching glacier. Years later, a hunter-trader named Quanga takes two jewelers onto the glacier to find the icy tomb of the King and retrieve his jewels. Clark Ashton Smith brings down upon the hapless thieves the ‘soul’ of the glacier, anthropomorphizing the frigid death of Hyperborea as a malign entity.

As a straightforward horror story of hallucination amidst encroaching death, “The Ice Demon” works well. Its theme of a dying civilization and its bleak loneliness makes it akin to the Zothique stories; perhaps Smith changed the tone to make this Hyperborean entry an easier sell to Weird Tales. The story’s language is also more direct and less ornate than customary for Hyperborea, but nonetheless Smith achieves the portraiture of the glacier as an intelligent force with his usual skill.

Fans of Robert E. Howard will notice a similarity between this story and the early Conan tale “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter.” Both contain astonishing dashes across arctic landscapes that have twisted into unreal worlds. The two authors wrote their stories roughly around the same time, so a direct connection seems unlikely, but the similarities nonetheless show the influence that Smith’s style had on other writers in the Weird Tales circle.

“The White Sybil”

Completed November 1932. First published in Science & Fantasy Book No. One (1934).

The end starts with the beginning, when Commoriom still stands and the glacier of Polarion has yet to advance across Mhu Thulan. Then the White Sybil appears, a fleeting beautiful presence whose lips bring word of the doom to come — not only to opulent Commoriom, but to all of Hyperborea. The young man Tortha falls under the trance of the alluring Sybil and follows her up into the glaciers, where he will receive a vision of the fate of the land. The concept sounds like a grand way to bring the Hyperborean cycle full circle, and the disillusioned romance holds promise, but “The White Sybil” feels like Smith should have spent greater time and detail on it. It reads like a sketch, and compared to the similar “The Ice Demon,” its transcendent, dream-like world has meager poetic effect. Understandably, Smith never managed to sell this story to a professional market, and it made its first appearance in a non-paying fanzine.

“The Coming of the White Worm”

Completed September 1933. First published in Stirring Science Stories, April 1941, in an abridged version.

Smith unleashed a last “serious” story of the northern continent before returning to his “grotesque ironies.” “The Coming of the White Worm” contains some of the densest, most archaic prose that Smith ever wrote. Smith frames the story as Chapter IX of the fictitious Book of Eibon, from a translation by Gaspard du Nord, the hero of the Averoigne tale “The Colossus of Ylourgne.” This device explains the complexity of the story’s diction, Byzantine even considering the author’s usual style. This poetic language made the story a difficult sell to the pulps. Eight years after writing it, Smith managed to sell “The Coming of the White Worm” to Stirring Science Stories, a short-lived pulp from tiny Albing Publications. Like its sister publication, Stirring Detective and Western Stories, the magazine survived for only four issues. Smith had to pare down many of his more oblique words to make the sale. The original version, which didn’t see print until 1989, begins:

Evagh the Warlock, dwelling beside the boreal sea, was aware of many strange and untimely portents in mid-summer. Frorely burned the sun above Mhu Thulan from a welkin clear and wannish as ice. At eve the aurora was hung from zenith to earth, like an arras in a high chamber of gods.

The abridgement removes the obscure words to create a more readable but less effective version:

Evagh the Warlock, dwelling beside the boreal sea, was aware of many strange and untimely portents in midsummer. Chilly burned the sun above Mhu Thulan from a heaven clear and pallid as ice. At eve the aurora was hung from zenith to earth like an arras in a high chamber of the gods.

The abridgement also changes some of the archaic inflections, such as “he who slayeth” to “he who slays.”

The events of the story, however, are identical in both versions. The sorcerer Evagh, living in Mhu Thulan during balmier days, witnesses the advent of a mobile iceberg that slays with a magical cold. The hideous white worm Rlim Shaikorth moves Evagh and his castle onto the iceberg to join other captive wizards as its servants. When the other wizards begin to vanish one by one, Evagh starts to suspect Rlim Shaikorth’s true reasons for needing servants.

Smith considered “The Coming of White Worm” a direct contribution to Lovecraft’s Mythos, but again the differences between the two men’s methods of examining extraterrestrial deities are startling. Smith does not leaven Lovecraft’s cosmic terrors with a soupçon of comedy as he does with the stories featuring Tsathoggua. Smith’s focuses instead on the entity, Rlim Shaikorth, as a fearsome personality who dictates to its followers like a grim Norse god. If Tsathoggua has a Greek pantheon influence, then Rlim Shaikorth belongs to the chilly world of the Teutonic gods.

Although it occurs in the early days of Hyperborea, the frigid whisper of the doom of Hyperborea blows through the story. It feels as if Smith was trying to make up for the flaws of the two ‘Ice Doom’ stories that preceded it. If so, he succeeds: “The Coming of the White Worm” remains one of the most frequently reprinted of all the Hyperborean stories and a superb piece of word-sorcery.

“The Seven Geases”

Completed October 1933. First published in Weird Tales, October 1934.

The term “geases,” like Avoosl Wuthoqquan’s “weird,” requires explanation. The Celtic word geas (pronounced gesch) means a magical compulsion, binding, or taboo, such as forcing a hero to go on a quest or prohibiting him from taking specific actions. In Celtic myths, a hero can receive a geas from a sorcerer, a king, or his parents, but most frequently from witches or hags whose path he crosses.

“The Seven Geases” has no plot in the traditional sense. Its structure compares best to that of a joke: a similar situation repeats over and over until a punch line flips around the understanding of all that has occurred before…or in this case, negates it with the written equivalent of a rim-shot punctuating a stand-up comedian’s bad joke. Ralibar Vooz, a noble of Commoriom and an expert hunter, makes an expedition into the Eiglophian Mountains to hunt the subhuman Voormis. But when he interrupts the magical ceremony of the wizard Ezdagor, the enraged magician casts a geas on Ralibar Vooz to send him deep under Mount Voormithadreth to the lair of Tsathoggua. Tsathoggua has no use for the hunter, so he sends him to spider-god Atlacha-Nacha. Who sends him to the inhuman sorcerer Haon-Dor. Who sends him to…

Farnsworth Wright initially rejected the story as “one geas after another,” but that is exactly the point. Ralibar Vooz’s wanderings deeper and deeper into the subterranean realms beneath the Eiglophians and his encounters with foul gods and lost races resemble not so much a story as a amusement park dark ride. Smith has a joyous time with the parade of grotesques; he often noted this story as one of his favorites. The humorous ironies are often hysterical: the rational Serpent Men dismiss Ralibar Vooz because there is “no place for [him] in our economy,” and a horde of non-corporeal dinosaurs make multiple attempts to eat the cursed man but can’t keep him inside their bodies. The crowning gag of “The Seven Geases” comes in its last paragraph. This punch line brings the story to the only conclusion it could really arrive at-even if it isn’t actually a conclusion at all.

Despite the satiric tone and playful horrors, “The Seven Geases” has much in common with the themes of H. P. Lovecraft’s Mythos. As in Lovecraft’s stories, humans here are nothing more than insignificant pawns to vast, uncaring powers. Life looks like a cosmic joke, ending either at the whim of vicious, uncaring deities, or at the whim of a random and capricious universe.

“The Theft of the Thirty-Nine Girdles”

Completed April 1957. First published in Saturn Science Fiction & Fantasy, March 1958.

Lack of success with the Hyperborean stories led Smith to stop writing them in 1933 and turn his energies to the more successful Zothique series. He went back to Hyperborea only once more, during his last phase of writing in the late 1950s. Appropriately, he returned to the character who started the cycle in the first place, loquacious thief Satampra Zeiros. The comic rogue recounts how he and his beautiful partner Vixeela tried to steal the thirty-nine bejeweled chastity girdles from the temple of the Moon God Leniqua in Uzuldaroum. Satampra Zeiros again drenches his language with smirking irony, such as claiming that he always “endeavored to serve merely as an agent in the rightful redistribution of wealth.” However, the story is a disappointment. It reads too dryly, and Smith seems to have scant interest in what happens. Nothing surprising or particularly fantastic occurs, and the conclusion feels abrupt and unsatisfying.

Fragments and Synopses

One of the mysteries of the Hyperborean stories is the ‘loss’ of one work, “The Voyage of King Euvoran,” to the Zothique series. Smith planned the story as a Hyperborean one filled with sardonic humor, but his obsession with Zothique turned the story into one of that far future continent-with the Hyperborean comedy intact. The story saw print in shortened form as “The Quest of the Gazolba” in Weird Tales in 1946. Smith presented his preferred version in his self-published pamphlet, The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies (Auburn Journal, 1933). This version also takes place in Zothique, so most likely Smith never finished the Hyperborean version.

The lengthiest fragment to survive is the fascinating “The House of Haon-Dor.” Smith includes the story in his list of entries in The Book of Hyperborea, but it has only a marginal connection to rest of the series since it takes place in the contemporary California Sierras. The fragment introduces Robert Faraway, a youth exploring an old hydraulic mining site who becomes fascinated with a strange abandoned cabin. The surviving synopsis continues the story, where the Hyperborean wizard Haon-Dor (encountered in “The Seven Geases”) possesses Faraway with a vampiric spirit. The fragment shows that Smith had considerable skill describing his own physical world (Northern California), and his prose portrait of the lonely hydraulic mining site remains a potent one. Unfortunately, the illness of Smith’s parents caused him to abandon this story, which had the potential to mix together the two worlds in which he lived: his real one and his literary one.

A few other brief synopsis survive: “The Hyperborean City” and another adventure of Satampra Zeiros called “The Shadow from the Sarcophagus,” and a handful of poems. After this, Hyperborea at last falls silent beneath the silencing ice.

Postscript

The Hyperborea series is more ‘difficult’ than Smith’s other fantasy cycles; its tone varies more than the single-minded bleakness of Zothique, and its setting is bizarre compared to the mundane medieval Averoigne. But no other of Smith’s works has had such an unusual medley of elements, with Lovecraftian themes rubbing against satiric jabs, elevated mocking language, black jokes, and a sense of a slow, chilly annihilation that cannot be escaped.

With all the fears of climatic global climate changes caused by environmental abuses, could we perhaps one day turn into the new Hyperboreans? A decadent culture with near-magical abilities that vanished beneath an unstoppable advance of ice?

I wouldn’t worry too much about it. Remember the words on the newly discovered tablets of the scribe J’oh Struh-mah:

An Ice Age is coming

But I have no fear

‘Cause Hyperborea is freezing

And I, I live by Mu Thulan.”

THE FANTASY CYCLES OF CLARK ASHTON SMITH PART III: TALES OF ZOTHIQUE

When Robert E. Howard discovered the character Conan in 1932, his writing took on a feverish intensity as the barbarian warrior turned into a literary obsession that allowed his creator’s natural skills and inclinations as a writer to bloom. Likewise in 1932, when Clark Ashton Smith discovered the last continent of dying Zothique, he knew that he had found the ideal setting for his poetic and dark imagination to run rampant. The lengthy series of Zothique tales (sixteen finished stories, a poem, and a one-act play) contains some of the most superb examples of Smith’s fiction work, with classic after classic pouring out at a quick pace.

In a letter to H. P. Lovecraft, Smith gave a tongue-in-cheek description of Zothique:

I have heard it hinted in certain archaic and obscure prophecies that the far future continent called Gnydron [Smith’s abortive early name for the continent] by some and Zothique by others, which will arise millions of years hence… and will witness the intrusions of things from galaxies not yet visible…

However, Smith did not write of Zothique simply as a bizarre future-world that serves as a magnet for the strange. He made it something darker and more powerful: the final stage of life on Earth. The opening of one of the finest stories of the series, “The Dark Eidolon,” provides an excellent summation of the peculiar qualities of this last land, where….

…the sun no longer shone with the whiteness of its prime, but was dim and tarnished as if with a vapor of blood. New stars without number had declared themselves in the heavens, and the shadows of the infinite had drawn closer. And out of the shadows, the older gods had returned to man…. And the elder demons had also returned, battering on the fumes of evil sacrifices, and fostering again the primordial sorceries.

In Clark Ashton Smith’s writing, humanity does not progress in a straight line but moves in cycles of rises and falls, with an emphasis on the fall. Zothique represents the period of entropy; the cyclic nature of history (as embodied by Poseidonis and Hyberborea, powerful civilizations that crumbled) cannot last forever and must eventually deplete all of its energy. The ‘weak’ sun that burns over the last continent shows how drained the world’s life-force has become. With no history ahead of it, Zothique literally has only the past: crypts, mummified rulers, and the hollow remains of metropolises. Few living cities exist, and “the sands of Zothique are full of lost tombs and cities.”

Zothique reverses the ‘Pangaea’ geological theory that all of Earth’s continents were once grouped together into a primeval ‘super-continent.’ Zothique is a single continent at the close of Earth’s history, but far from a conglomeration of all lands, it is the only piece of land that remains. Progress has failed along with land; sorcery has reclaimed the role that science usurped from it millennia ago, much like in Jack Vance’s later “Dying Earth” books, which have much thematically and stylistically in common with Zothique.

Mortality defines the majority of the stories. Although a fixation on death permeates Smith’s oeuvre, in Zothique it stands on a funeral pyre and shouts its name as the flames devour it. The writer’s earlier fantasy settings of Hyperborea and Poseidonis are both doomed lands, but Zothique is the last doomed land, the death rattle of the planet Earth. It is an “End of History” scenario; its end is the world’s end, and nothing will come after. This is death as complete oblivion, not an opportunity for rebirth.

Since they have no concept of a future, the people of Zothique live as if there were no tomorrow. Their sensual decadence forms an important sub-theme of the series that emerges strongest in the later works. The elites of the great cities live in perfumed splendors and sexual excess, as in “The Dark Eidolon” and “The Garden of Adompha.” Funerals, such as in “The Death of Ilalotha,” are cause for drunken debauchery instead of reverence. No other of Smith’s stories strain so forcibly against the boundaries of the erotic; he even planned a short Zothique novel, The Scarlet Succubus, which he claimed would explore “the imaginative and mystic possibilities of sex,” apparently outside the prudish constraints of magazine publication of the time. Sadly, work on it never progressed past the idea stage, and we are left only with the dark sexual titillations of the later Zothique pieces.

According to Smith’s letters, Zothique lies in the southern Atlantic and comprises Asia Minor, Arabia, Persia, India, parts of northern and eastern Africa, and the Indonesia archipeligo. A “new Australia” exists in the south, probably the large island of Cyntrom. The people come from Aryan (in the older use of the term) and Semitic stock. A sketchy geography can be worked out from the stories themselves. The principal lands are Yoros, renowned for its wine and its capital of Faraad (also spelled Pharaad) on the southern sea; Tasuun, a desert realm with its capital at Miraab, which replaced the cursed city of Chaon Gaca; Xylac, a decadent kingdom with its capital at Ummaos; the eastern land of Ustaim; the gray country of Tinarath; and the wastes of Cincor. In the northwest is the black kingdom of Ilcar, although it remains on the fringes of the stories. There are three islands of repulsive repute-Naat, Sotar, and Uccastrog-that harbor particularly vile customs, such as the torturers of Uccastrog and the necromancers of Naat.

The composition of the Zothique cycle falls into three phases. The first ten stories cover the last two years of Clark Ashton Smith’s longest sustained period of prose fiction production, 1928 through 1934. When Smith took up fiction again in late 1935, he completed four more Zothique stories. In the late 1940s, he again made a brief return to the last continent for a final gleaming of its moribund sun. When Clark Ashton Smith died in 1961, he was still planning to get his complete “Tales of Zothique” collected and published.

His wish would come true more than a decade after his death, when Lin Carter published the collection Zothique as part of his Adult Fantasy series for Zebra Press. Carter included a map of Zothique that Smith had approved and emended during his lifetime. Carter arranged the stories in a dubious chronological order based on vague internal references. While the Hyperborea and Averoigne stories have some obvious chronological relations, Zothique contains few. Approaching the series in the chronological order of their composition (based on Smith’s notes), as Necronomicon Press did in their 1995 collection, Tales of Zothique, presents the stories in the best light. The following overview uses Necronomicon’s order.

“The Empire of the Necromancers”

Completed January 1932. First published in Weird Tales, September 1932.

The opening paragraph of the inaugural Zothique story immediately casts a potent spell. Clark Ashton Smith had found his new fictional home:

The legend of Mmatmuor and Sodosma shall arise only in the latter cycles of Earth, when the glad legends of the prime have been forgotten. Before the time of its telling, many epochs shall have passed away, and the seas shall have fallen in their beds, and new continents shall have come to birth. Perhaps, in that day, it will serve to beguile for a little the black weariness of a dying race, grown hopeless of all but oblivion. I tell the tale as men shall tell it in Zothique, the last continent, beneath a dim sun and sad heavens where the stars come out in terrible brightness before eventide.

All writers strive for paragraphs of this potency, which impart more to a reader about the story that follows and its theme, mood, and setting than the words on the page at first indicate. Without giving a history or survey, Smith expresses a vivid portrait of Zothique’s essence that goes beyond this one story to encompass the whole cycle. Words crash like hammers onto anvils, words we shall come to know well in the stories that follow: ‘black weariness,’ ‘dying race,’ ‘hopeless,’ ‘oblivion,’ ‘dim sun,’ ‘sad heavens.’

“The Empire of the Necromancers” tells of the fatigue of a race that yearns for oblivion. It is not a dying race, but one already dead: the population of Cincor perished in an epic plague that left a desert of skeletons and sun-withered mummies in its wake. Two exiled sorcerers raise the kingdom from the dead and enslave the shambling corpses, letting them shuffle about in forgetful imitations of their former lives. But the strength of longing for true death proves too powerful for the former living of Cincor, and the first and last rulers of the royal family awaken from their thralldom to plot revenge against the sybaritic sorcerers who cheated them of death’s release.

“The Empire of the Necromancers” is frequently cited as Smith’s greatest work of short fiction. It is an ideal curtain-raiser for his most fully realized fantasy opus.

“The Isle of the Torturers”

Completed July 1932. First published in Weird Tales, March 1933.