THE RESTORATION OF GERMAN LIBERTY

Miguel Serrano collected works https://archive.org/details/miguel-serrano_202312

“The Reich is no longer a defenceless plaything. It is no longer at the mercy of foreign predominance. Its defence is assured. We can feel this tranquil sense of security all the more deeply because the German people and their Government have no other object in view than to live in peace and friendship with their neighbours. We look upon our Army as the protective barrier behind which the Nation can work in peace

Adolf Hitler.

Digitized by Propagandaleiter

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY M. MÜLLER & SOHN K. G., BERLIN SW 19

THE RESTORATION OF GERMAN LIBERTY

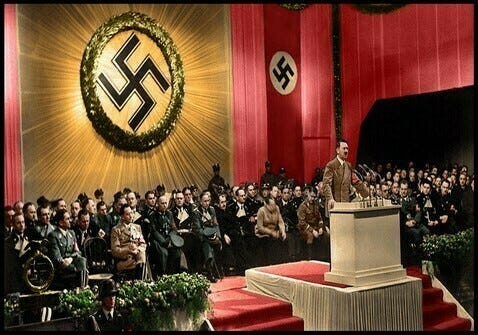

Opening Address

at the Seventh National Socialist Congress, Nuremberg, September 11, 1935

FELLOW MEMBERS

OF THE NATIONAL SOCIALIST PARITY:

T

HE Congress in which we are now assembled is the Seventh Congress of the National Socialist Movement. It is sixteen years since the Party was founded, and

twelve years since our first revolutionary rising. Eleven years ago the Party was founded a second time. And we are now in the third year of our final victory. What tremendous experiences we have been through within the span of about a decade-and-a-half!

When we began our struggle Germany was in the throes of a chaotic disruption. Those who were then guiding the destinies of the German people were about to make shipwreck of the national honour, together with our national strength and liberty. A nation which had given such high proof of military valour was politically bartered away and betrayed by its own rulers. And today, after sixteen years?

In 1933 we called our Congress the Victory Congress and we had good right to do so; for we considered the final establishment of National Socialist power as the characteristic mark of that period. For a similar reason, we can proudly designate the present celebrations as the Liberty Congress of the Reich.

We are all so impetuously carried along in the swift rhythm of events that it is difficult for the individual to realise sufficiently the immediate and ultimate significance of what has happened. It must be left to History to record how within the span of less than three years since our accession to power a revival took place in Germany which our adversaries certainly had not foreseen and which certain indifferent bourgeois elements have not been able to comprehend but which we, National Socialists, have always believed in with an ardent and indomitable faith. This revival will be judged in history as an honourable liquidation of the bankruptcy which took place in 1918. It was just where Germany suffered from the severest collapse that the greatest revival took place.

And thus it is that we have always felt this inner recovery of our people to be the most essential element, together with the restoration of the political honour of the nation and therewith the restoration of our human dignity also. The importance of all that we have

achieved in the various other branches of national life during the last three years is insignificant in comparison with this inner re-awakening.

The urge for self-preservation on the part of the community as a whole unfortunately embraces the egoisms of millions of individuals. And in our case the individuals were hard hit by the crisis which they had to face in their daily lives. The peasant naturally thinks of the returns he derives from his toil. The worker thinks of his daily wage and the artisan busies himself with the problem of how his wares are selling. The landlord worries about the rents that his property brings in and the industrialist thinks of the returns that come from the output of his factory, just as the unemployed broods over the chances of getting work or on the amount of his dole. Each person feels his own troubles and thinks them the most essential. He feels the weight of his own miseries as the hardest burden of all. But they are bad times indeed when the individual becomes blind to the general condition of things around him and fails to consider or understand the great laws which govern the collective march of events and thereby determine the life of the individual himself.

On the occasion of this Third Congress since our accession to power we, National Socialists, can look back with pride over all that has been accomplished during the past three years, even the merely material results that have been achieved in the various spheres of public life. If we consider the people as one great organism and if we realise that each piece of work, no matter where it be done or what form it may take, is to the ultimate gain of the whole organism, then we shall be able to form at least a general idea of how much our people have benefited by virtue of one fact alone, namely, that the unemployed-who numbered over six millions-have been reduced to one million and three-fourths. In this we have rendered the nation a service which the individual cannot easily estimate at its true value.

Since our advent to power we have replaced about five million people in the circuit of national production. This means that for every working day we have given to the German people an average of between thirty and forty million hours of work more than they had previously. This has been their salvation. It does not matter for what kind of production this working power has been employed in the individual cases. Taken all in all, in one year we have given to the nation the fruits of about nine milliard hours of labour.

This gigantic achievement, which is distributed in its activities and effects throughout the whole sphere of our national production, is not for the benefit of some individual millionaires. Directly or indirectly, it is bringing about an improvement in the general conditions of living and accordingly enhances our national existence. We know from experience that the damages accruing from fifteen years of progressive dissolution could not be repaired completely within the short span of three years. But what we have done will be supplemented by further restoration in the various spheres of national existence. With the passing of time it must necessarily result in raising not only the general standard of living and the cultural level of the German nation as a whole, but each individual German will be able to perceive and feel the benefit of it in his own life. As regards those results which have been produced by the national effort in the multifarious branches of our economic life as a whole, within three years of National Socialist leadership, you will have a detailed account laid before you in the series of special lectures which are to be given during the course of this Congress.

It has been a magnificent performance. Yet it is only secondary when compared with the work which we have done, by adhering loyally to our programme, in restoring the honour

and liberty of the nation. For if this restoration had not taken place, all other measures would have been in vain. That is especially true in a world and at a time where unrest prevails to a degree that has never before been experienced and where we are farther removed than ever before from the so-called rule of a higher justice.

You will all understand what is in my mind if I ask you at this festive moment to lift your eyes above this hall and take a broad glance at the great world beyond the frontiers of the German nation. Unrest and insecurity are the striking features of the spectacle that meets your gaze. Right is weak and Semblance rules the world. But woe to him who is weak himself! The stronger will take his possessions from him and use them as the grounds of a moral argument to justify his subjugation. Slaves are made where slaves are emancipated. Classes are born where classes are annihilated. The Marxist theorists who preached the doctrine of “Never Again” during the War are now constructing colossal machinery for the purpose of war. The apostles of international conciliation are filling the world with intolerant hatred and are infamously inciting the nations against one another. Those who have signed alliances of peace are studying the possibilities which may be offered by the coming war and the methods to be used in the waging of it. In short, the man who is forced to walk defenceless in this garden of dragons has every good reason to feel ill at ease. For a long fifteen years our nation has had this experience of being delivered over to mercy or destruction at the hands of every comer, whether of good will or of evil will. We have been given the opportunity of proving by practical experience the value of sympathies extended to a person who, when once down, would still hope for justice or at least understanding. Where are Wilson’s Fourteen Points and where is the world today?

We, Germans, can now contemplate the situation in a spirit of profound tranquility; for the Reich is no longer a defenceless plaything. It is no longer at the mercy of foreign predominance. Its defence is assured. And its defence is assured not through alliances and pacts, treaties of mutual interest and general agreements, but it is assured through the determined will of its leaders and the effective forces of the nation. It is not necessary for Germany to give any demonstration whatsoever of this security before the other nations of the world. It is enough that we ourselves know it.

Not only that, but we can feel this tranquil sense of security all the more deeply because the German people and their Government have no other object in view than to live in peace and friendship with their neighbours. The international hate- mongers, whose sole yearning is to see Europe turned into a field of slaughter, are so well known to us that we can make no mistake as to the ground and object of their hopes. The more International Jewish Communism believes that, once universal chaos is spread throughout Europe, it can raise the standard of revolution and establish the despotic rule of the Bolsheviks over the nations of Europe, at the sacrifice of their liberties and their standards of life-the more determined are we, National Socialists, to see that they will first have to reckon with the true significance of the restoration of our defence force and will have to appreciate it at its full value. For we have the honour of being civilisation, is to go to pieces and disappear. Inasmuch as we have put this conviction into practice as far as the German people are concerned, we believe that we have given a useful example to the other European States.

After a struggle lasting fifteen years the National Socialist Party succeeded in finally overthrowing Communism throughout Germany. Beyond the machinations of some Jewish wire-pullers, it is no longer active except in the brains of a few incorrigible fools and visionaries. In saying this, I do not mean to include those international criminals who are to be

found under all governments and among all nations. These veteran clients of jails and penitentiaries saw in the Bolshevik revolution the rising sun of liberty and therewith scented opportunities that promised success for renewed activities.

We have no illusions however as to the fact that a latent danger still exists and will continue to exist for some time to come. Therefore we are always armed and ready for any kind of action that may have to be taken at any moment. Our Party is a militant Party and has hitherto succeeded in bringing everyone of its enemies to the ground. Should any such phenomenon raise its head again our Party will certainly not fail to meet it and give further proof of the mettle which was shown when fighting those same enemies in the past.

Some well-intentioned but rather naive advisers ask why we take such a combative attitude towards these movements if the instigators of them are numerically so few as we ourselves admit. Why are we not a little more lenient and leave them to themselves? Here I shall give the answer to you, my Party colleagues and to all our German fellow citizens. You will kindly take the following declaration as conclusive once and for all:

“Our enemies had fifteen years, and before that even fifty years, in which to give proof of their abilities. Morally, politically and economically they allowed Germany to go to ruin. We have nothing more to do with these people. We have power in our hands and we shall hold it. And we shall not permit anybody to have his way who tries to organise something against this power; but we shall throttle every movement at the very instant that it shows itself. Now that we have restored and reconstructed Germany, through an effort that cannot be described in words, our enemies would be only too ready to do as they did before and barter away the honour and freedom and substance of the nation.”

No. Let nobody permit himself illusions in our regard. It is just because we know how ridiculously small is the number of our enemies that we, as the sole mandatories of the German people, shall suppress those enemies the moment they dare even to give any sign of their activities. The strong protection which is afforded them by their friends abroad does not disconcert us. It only confirms us in our determination.

What the German people may expect from these elements is made strikingly clear by the fervent hopes which their activities raise among all the international forces arrayed against Germany. When such activities are observed they are acclaimed and encouraged. Our bitterest enemies send them their warmest greetings. It indicates how grossly the mentality of the German nation is misunderstood when people believe, both on the one side and on the other, that such an alliance could disturb the foundations of a State whose leaders have placed the national honour in the foreground as the guiding ideal of all their conduct. Indeed the greatest recommendation which the National Socialist Movement enjoys is that it does not depend for support on this international protection.

In considering those domestic elements today I should like to analyse their motives and their methods of action for you and through you for the whole nation. In the struggle which we waged for fifteen years to acquire political power in Germany we came to know three leading classes of opponents who were artificers of German disintegration. Each group is conditioned by the other and all alike must be held responsible for the German debacle. They are:-

Jewish Marxism and the parliamentary democracy associated with it.

The politically and morally obnoxious Centre Party.

Certain incorrigible elements in the stupid and reactionary bourgeoisie.

For a long fifteen years we had these three sorts of people to fight against. That gave us the opportunity of coming to know them thoroughly. Despite the fact that they held power in their hands and applied that power without any scruple, despite an unrestrained terror in which hundreds were murdered and tens of thousands wounded, despite the barbaric attack on the women and children belonging to the families of our comrades, whereby the father was deprived of his means of livelihood and his wife and children thus condemned to starvation- despite it all, National Socialism finally triumphed over these three classes of political enemies.

In Moscow today they are making advances to the clique of political clerics who formerly belonged to the Centre Party and also to the reactionary bourgeoisie. But that does not come as a surprise to us, National Socialists. During the period of our struggle we had reason to know that each of these two parties worked in the closest alliance with the other. Hand in hand they used every available means to prevent the national resurgence of Germany. Today they cannot wipe out the remembrance of this by merely trying to forget it themselves or by repudiating the truth of the fact in a fury of pretended indignation.

When these three classes were wiped out by the National Socialist Revolution in March 1933 the most practical course for them would appear to have been to acknowledge themselves as finished. They no longer held power. The results of their criminal mismanagement and their default in every branch of administration were still so fresh in the memory of the nation as to indicate to them that they ought to disappear at once from public life. Yet in face of overwhelming evidence to guide them they profoundly misjudged the situation and stayed on. In their arrogance it seemed to them entirely beside the mark to try seriously to understand the principles of National Socialism, even as an opposing doctrine. So they got into their heads the idea that the year 1933 signified nothing more than just a change of government. They thought that what had happened was that a new engineer and a new crew had stepped on to the locomotive of the train called “Das Reich”.

And now they thought that they needed only to have a little patience and wait until the new crew tired of its job or that one day it would find that it could not carry on and would depart of its own accord. Moreover, they may well have thought that the new men, following the example of their predecessors, were just out for business and would retire, sooner or later, when their appetites were satisfied. And thus one can understand their decision to accept the fait accompli with an air of bitter-sweet nonchalance and, like honest spectators, await the result of the race with high hope in their hearts.

But what then escaped their comprehension was the fact that it was not merely that the crew of the locomotive had been changed, but rather that the train had begun to take a new direction. The points on the German railway had been switched from the old route.

And now, after three years, they who nourished those secret hopes find to their great discomfiture that the train is leaving them farther and farther behind every day. And so they often forget to maintain their attitude of assumed indifference. They cannot conceal either their folly or their disillusionment. The more unreasonable among them, who seem to be the youngest and therefore the least experienced, think that if they now run fast enough and shout

loud enough they may be able to stop the disappearing train and overtake it. But they will stumble and fall over in making the effort. To the Marxists and especially their Jewish instigators the following lesson must be read:-

“If the bureaucracy defaults in fulfilling its duties the German people will replace it with their own active organisation. With perhaps too great a measure of benevolence, we made it possible for them to maintain a discreet attitude and with the passing of time thus allow certain things to fade into oblivion. We now have the impression that this indulgence was wrongly interpreted. The results which were bound to follow have actually occurred. In pursuing its course the National Socialist State will definitely overcome this danger too. In this connection I may here state categorically that the fight against the domestic enemies of the nation will by no means halt before a formalist and inefficient bureaucracy, for wherever the State bureaucracy shows itself incompetent to solve a problem the German nation will substitute its more vigorous organisation to see that its vital necessities are assured.”

For it is a gross mistake to believe that the nation exists for the sake of some formal institution and that if such an institution should prove incapable of accomplishing the tasks laid before it the nation ought to capitulate in face of these tasks.

On the contrary: What can be accomplished by the State will be accomplished by the State. But whatever the State, by reason of its structure, is not in a position to accomplish that will be accomplished by the National Socialist Movement.

For the State is only one of the organic forms in which the life of the people is expressed. But it is animated and dominated by the immediate manifestation of the national will to live, and this immediate manifestation is the Party and the National Socialist Movement. In certain circles, where eyes are still fondly turned to the past and old experiences held in esteem, the idea may have struck root that, just as former governments with their normal machinery of State were not able to cope with Jewish Marxism and its allied phenomena, so the German State of today will have to capitulate because it cannot convince its contemporaries that there are not certain definite problems which are beyond its competence.

That is another big mistake. The Party, the State, national economy and administration, are all only means to an end. And the end is the maintenance of the nation. This is the fundamental principle of the National Socialist system. Whatever is manifestly prejudicial to the well-being of the nation must be suppressed. If an institution of State have shown itself incapable of discharging this duty, then it will have to give way to another which will see that the task is carried through. All of us, my Party colleagues and above all you who hold leading positions in the State and the Movement, will be judged one day not by the rectitude of the formalist attitude we adopted but on the grounds of how far we have or have not put our programme successfully into practice. This means that the question will be: how far we have or have not protected and secured the existence of our race and nation. The following principle must especially be insisted upon and carried through in practice with what I may call a devoted fanaticism: namely, that an enemy of the National Socialist State, no matter whether at home or abroad, must not know or discover any person or source in Germany that will agree with him or support him.

We live in the midst of a world that has grown turbulent. Only the most rigid principles and the relentless observance of them will enable us to save Germany from also falling into

the Bolshevik chaos, the existence and menace of which we have unmasked in many quarters and pointed out as a warning. It is quite easy to understand why our enemies do not like these principles. We need not be disturbed by the fact that at the present moment the justice and absolute necessity of them are not everywhere recognised outside of Germany. For it may be that within a short period of time the world will no longer have to face the question as to whether these principles of ours and our line of conduct be acceptable or not, but will rather have to face the immediate alternative of stumbling into the human catastrophe of Bolshevism or saving itself by the same or similar methods as we have adopted.

This determination to deal remorselessly with certain dangers the moment they appear and cut them up root and branch will be carried out irrespective of circumstances. If it ever should become necessary, we shall not hesitate to take those functions for the discharge of which the State is manifestly unfitted -inasmuch as they are foreign to its inner character-and bring forward legislation that will transfer them to other institutions which seem more efficiently equipped for the settlement of such matters. But in this regard the decision will rest exclusively with the leadership of the Party and shall not depend upon the will of individuals. Our discipline is the source and mainstay of our power. In this connection I shall consider in detail the dangers which arise from the political activities of religious denominations. My reason for doing so is that we have seen for a long time now how this phenomenon is closely associated with Marxism.

Here I wish to state certain principles expressly:-

The Party never had the intention, and it has not the intention now, of engaging in any kind of hostilities against Christianity in Germany. Our aim has been quite in the opposite direction. We have sought to unite the various regional Protestant churches, whose conditions of existence were impossible, and create one great Evangelical Church throughout the Reich, without interfering in the slightest with questions of religious belief or practice. By concluding a concordat with the Catholic Church, the Party has sought to establish a state of affairs which would be beneficial to both sides and which would be of a permanent character. The Party has abolished the organisations that belonged to the Atheist Movement and while doing this it has cleared our whole life of innumerable symptoms the suppression of which is or ought to be the task of the Christian denominations.

But on no conditions whatsoever will the National Socialist State permit religious denominations to engage in political activities, whether these activities be a continuance of the old tradition or whether they be something started afresh. And here I should like to issue definite warning against the entertainment of any illusions whatsoever in regard to the fixed determination of the Movement and the State. We have already fought the clerical politicians and we have forced them to leave Parliament. It was a long struggle and during the course of it we held no public power whatsoever, whereas the others held all the power in their hands.

But today we have this power and it is easier for us to maintain the struggle on behalf of the principles I have mentioned. Yet we shall never turn this fight into a fight against Christianity or against any of the two great denominations. Yet we shall carry on this fight for the purpose of preserving our public life free from those priests who have forgotten their vocation and practised politics rather than the care of the souls. We shall also carry on the fight to unmask those who pretend that their Church is threatened, while the truth unfortunately is that they themselves are only looking for the opportunity to be free of it. I need not assure you that we, National Socialists, have not sought this quarrel. For we know

what the Jewish-Bolshevik menace is, as it threatens the world today, and we are too keenly aware of it not to wish that all forces could be united in combatting it. Had Communism succeeded, the problem of the twenty-six antiquated regional churches and that of the Catholic political Centre would have been quickly solved. Wherever Bolshevism has come to hold political power the “militant churches” present a picture that is essentially more inglorious than that presented by the “militant” National Socialist Movement in Germany which, with the sacrifice of innumerable martyrs, has beaten and routed the Communist murderers and incendiaries.

The third group of our opponents must be looked upon as pathological specimens. They are men who have come at last to understand that the present State and the nation, in the task which has been undertaken and the speed with which this task is being discharged, as well as in the greatness of the general achievement, are entirely beyond the ambit of their obese intelligence and their sluggish will power. Instead of realizing that their existence is now entirely superfluous, they still pray to their old God and implore of Him to cast the future in the mould of the past. As long as they continue to brood over this yearning in quietude we shall have no occasion to disturb their reverie. But if any attempt should be made on the part of these groups, which are associated with one another by common traditions, gradually to express their secret desires in the open, such an attempt shall be suppressed forthwith. The German people do not wish to listen to that music any longer. At one time they venerated the composers of it; but they have no respect for the degenerate successors and petty conductors who strut about like ghosts from the bourgeois past. That world is dead. And the dead should be permitted to rest in peace.

If we pass in review all the elements who believe that they cannot be reconciled to the new Germany at any price, then we shall readily arrive at the following conclusions:-

They are united only on negative grounds: that is to say, they look upon the present State as their common enemy. Otherwise there is not a single idea that unites them.

What would Germany come to if this motley group should ever regain influence and importance? For many centuries our people were rent asunder, divided by conflicting beliefs and different outlooks on life in general; at first tribal, then dynastic, then religious, finally divergent political opinions and views of life. When we, National Socialists, were carrying on our campaign for the acquisition of power thirty-seven political parties in (Germany were wrangling with one another for popular support. There were two churches and innumerable societies for the promotion of various other beliefs. After a long struggle, which was principally a systematic endeavour to instruct the nation in the principles that govern public life, and after making untold sacrifices, we succeeded in bringing nine-tenths of the people to our way of thinking and in uniting them under one will. The remaining ten percent represent the leavings of the twenty-seven parties, the intractable elements of the religious denominations, the former societies for the promotion of one thing or another; in short, those elements that for centuries were responsible for Germany’s woes by reason of the fact that they kept her divided. When we calmly review the whole situation now and take account of the successful work that has been done for our German Reich during the past few years, then we shall once again have to conclude that the most valuable achievement of all was and is the fact that the movement welded the Germans together in one nation and developed a common will for united action.

Consider the sense of security and peace that reigns over Germany today. If we look elsewhere we see factors of dissolution and decomposition at work almost everywhere, strikes and lock-outs and street brawls, destruction of property, hatred and civil war. The wandering scholars of the deracinated international-Jewish clique are moving in and out among the peoples, fomenting trouble and disorder, preaching a hate that is contrary to all sound reason and inciting human beings and nations against one another. Under the pretext of representing class interests, they are trying to mobilise the public for civil war, for the sake of their own private interests and satisfaction. And we see the results.

In a world which ought to live in abundance misery is prevalent everywhere. Countries so sparsely populated that they have less than fifteen people to the square-kilometre (less than twenty-four to the square mile) are suffering from hunger. States which have unlimited resources of raw material cannot reduce the masses of their unemployed.

Our country has a population of 137 people to the square- kilometre (220 to the square mile). We have no colonies and lack most of the raw materials which are necessary for us. For fifteen years after the war we were bled white. We lost all our foreign property and the capital we had invested abroad. We had to pay fifty milliards (2,500,000,000 pounds sterling, at par) in reparations. Thus Germany was brought to the verge of complete ruin. Yet we have maintained our powers of existence, though we had to pass through periods of poignant anxiety in doing so. We have reduced the numbers of our unemployed, so that we are actually in a better situation today than some of the richest countries on the globe.

The special lectures which are to be delivered at this Congress will give you, my Party colleagues, an account of the efforts that had to be made in order to achieve these results. Then you will understand the magnitude of the task that had to be undertaken to solve the most pressing problems.

When we took over power Germany was in a condition of complete decadence. Our adversaries prophesied that we could not last more than a few weeks. And since then they have obstinately continued to predict our downfall, even though they have had to keep on postponing it from one date to another. But their prophecies have been contradicted. The opposite has happened. Of course we are a poor nation, not because National Socialism has ruled for twenty years but because criminal party governments allowed Germany to drift, not only towards revolution, but-what was far worse-into profound inner chaos, and because for fifteen years the German State was the defenceless object of every kind of international chantage.

Our great triumph has been that through an heroic struggle for the assertion of Germany’s national independence we succeeded in reconstructing the defensive forces of the nation, so that for all future time it may be spared the terrible experiences through which we have passed in recent years.

In taking this occasion, my colleagues, to give you a short account of what has been done within the past twelve months my idea is to show you how we have fulfilled the task which we set before ourselves last year and to outline the tasks that we have to face for the future.

The National Socialist Party:

The last Party Congress was held just as we had overcome an inner crisis of the Movement. In that crisis some foolish elements in our ranks, entirely forgetful of their obligations of honour, endeavoured to transform the Party into an instrument to serve their own private ends. Since our last Congress we have eliminated even the final remnants of that attempt. In the meantime the Party has been extraordinarily consolidated. Its inner organisation has been further perfected. Numerous positions in the State have been taken over by members of the Party. Fate has unfortunately taken from us, before his due time, one of our stoutest combatants. The death of Schemm meant the loss of an apostle of the National Socialist Revival.

The essential aim of the internal reorganisation of the Party was to fix a new delimitation of the various duties, which the respective branches of the Party have to fulfil. That became necessary once the revolution had completely reached its goal. First of all, it was necessary to make our members realise fully that with the restoration of the Army the National Socialist State acquired a new supporting pillar in its structure. This Army has a duty to fulfil which is entirely exclusive to it. Hence it follows that there must be not only a strict delimitation of the activities of the Movement, but also that certain organisations of the Movement have to be liquidated because they were constituted specially for the purpose of suppressing disorder.

The administrations of the SA and the SS have been very much simplified during the past twelve months and the membership of those bodies has been subjected to severer tests. The result of this is that a numerical reduction has taken place and therewith an improvement in quality.

The feeling of close solidarity among the older National Socialists has by no means relaxed. In fact it has become more profound. Just as in the past, this year’s Party Congress has afforded a welcome opportunity for our veteran comrades to meet once again and enjoy one another’s company. The young recruits who have joined the Movement will not change the character of this militant political elite of the German nation. They will rather reinforce it.

The State:

The cause which has been inscribed on the banners of the National Socialist Movement ever since its reconstruction (in 1924) has been advanced in a manner which is without a parallel in history. The Reich has gradually and steadily passed over to National Socialism. The effective influence of the movement has never before been so clearly demonstrated as within the past twelve months. Germany has become free. On the 16th of last March the National Socialist Government gave the nation equality of rights by virtue of its own inner power. The reestablishment of the Army has given Germany the necessary protection on land. The building up of our air force has assured the German home against fire and gas. The new navy, whose tonnage was fixed by the London Agreement, protects German commerce and the German coasts.

Those twelve months, from this time last year to now, have witnessed important internal reforms in almost all branches of our legislative and administrative activities. Compulsory labour service has been introduced.

The German Economic Situation:

We have good reason to speak of this today. The year 1934 unfortunately brought us a very bad harvest. We are still suffering from the effects of it. However, we have succeeded in maintaining the supply of all primary foodstuffs necessary for the support of the German people. But this was at the cost of an effort which is not estimated at its full value by the great masses of the nation. The bad harvest resulted in a temporary shortage of certain food commodities. But we were resolved not to capitulate, no matter what the cost might be, although certain sections of the international press looked forward to that capitulation with yearning hopes. And now we have successfully surmounted the crisis.

In doing so we felt it incumbent on us at times to take measures against those who raised their prices on the excuse of the bad harvest. This rise in prices was quite comprehensible in some cases, but in others it was quite unfounded.

In carrying through these efforts the National Socialist economic administration followed the principle that under no circumstances could we permit a rise of wages or salaries and under no circumstances a rise of prices; because wherever one of these happenings is permitted the other is sure to follow as a necessary result.

During the past twelve months we steadfastly held to our determination-and we shall do the same in the future-that we would not allow the German nation to be stampeded into a new inflation. But even today an increase in wages or prices would necessarily lead to such an inflation. There are some unscrupulous egoists today, or short-sighted people incapable of reasoning, who think that they have the right to take advantage of certain difficulties that have occurred in the supply of food commodities and that they can increase their prices for that reason alone. If the Government were to permit such conduct to go on, prices would rise with an increasing velocity, such as we experienced from 1921 to 1928. The result would be that the German people would soon find themselves in the midst of a new inflation. All such attempts will be suppressed by us and we shall show no mercy in doing so. If peaceful warning should not succeed then we shall not hesitate to send recalcitrant individuals to the concentration camps, so as to teach them that the good of the community as a whole must prevail over personal desires.

Of course the Government might have spared itself much preoccupation, at least temporarily, if it had followed the example of many other States that have inflated their currencies, thus permitting the devaluation of the German Mark. But we have not allowed ourselves to be attracted towards that alternative: first, because, although it might eliminate some of our worries, sooner or later it must necessarily have brought much more serious affliction on millions and millions of our fellow citizens. By this affliction I mean the grave disappointment to which those people would be subjected who, having confidence in the State, had saved up part of their earnings and would now have to see the value of those savings dwindle, owing to the devaluation of the currency. The second reason why we did not take this alternative course is because we firmly believe that the international world crisis will never be overcome while such methods are practised. We are absolutely convinced that an indispensable prerequisite for remedying the international commercial crisis is the introduction of a stable monetary system. Such a course would permit the transformation of a prehistoric system of exchange into a free and modern commercial system Moreover, the National Socialist Government is resolved that under no circumstances will it be drawn into the old commercial system of creating debts, but that it will rigidly abide by the principle of

importing from abroad only up to the value of the goods that it sells abroad. If certain individuals should feel distressed because they cannot purchase this or that article of luxury, or even some useful object or other, because we have not imported it for them, our answer to such worthy compatriots is: We are troubled enough as things are with the problem of feeding the German people. As long as we cannot be perfectly assured that the necessities of life are at hand for every single member of the community, we are not interested in the question whether this or that article of luxury might be imported. If there are people who think that they cannot get along without certain articles of luxury for life’s embellishment the only course left for such people is to turns their backs on this poor Germany of ours and migrate to more propitious countries where their desires will be more abundantly satisfied. Perhaps they might go to Soviet Russia.

Anyhow, our principle is not to create any new debts. As a matter of fact, we have succeeded in paying off a considerable portion of our international indebtedness. Furthermore, we have succeeded in lowering the interest on part of our foreign debts and also on our domestic loans.

In order to be able to purchase those foodstuffs and raw materials abroad which we lack in Germany, the Government has encouraged German export for the purpose of maintaining it at the normal level. As a matter of fact, Germany’s share in international trade has not diminished except proportionately to the falling off of the export trade in other countries, despite the Jewish world boycott against us.

But in so far as our export trade is not sufficient to procure us the means of purchasing the needful foodstuffs and raw materials abroad we have decided to manufacture those raw materials ourselves and thus make Germany independent of foreign supplies. Here there is no question of producing “substitutes” but of material that is quite equal to the imported material and other material that is entirely new.

For instance: The production of petrol by a process of coal extraction has been organised on a large scale. In the near future this will keep new factories occupied incessantly and thus we shall be able to supply an increasing percentage of the explosive fuel needed in our trade and industry. This supply will be entirely a home product. We are resolved to develop the manufacture of German fibre for the purposes of clothmaking. The problem of manufacturing artificial rubber is now solved. We have already begun to lay down the plant necessary for this industry.

In numerous other directions similar progress is taking place, such as the exploitation of our own oil resources and the mineral deposits in various parts of the country. Parallel with this work, we are putting into effect a very broadly-conceived plan for the territorial reorganisation of our industries. The German people must also take into account the fact that we have to provide not merely for the demands of private industry and commerce but that we also have to provide the material necessities for the reconstruction of the German Defence Force.

At the same time the German Government is occupied with the problem of developing the transport services. All the projects which have been put in hand are being energetically carried through and additional projects have been accepted and sanctioned. The motorisation of German traffic shows a rapid progress, which is the counterpart of the progress that is being made in building great motor roads throughout the Reich. The most significant evidence

of the energy and activity of our economic administration is the fact that during the past twelve months the number of men to whom we have given bread and work has been raised to five millions.

But as yet our efforts have not succeeded in providing work for all. In the case of those individuals who are still without work, and in the case of those whose earnings are not sufficient for the support of themselves and their families, our social relief organisations have come to the rescue. Of course even these cannot satisfy all hopes. But where, in the whole course of history, do we find a parallel example of such a gigantic achievement? If we consider that in Soviet Russia, where there is a population of less than fifteen persons to the square- kilometre, millions of people live under the menace of famine and the number of people who die of hunger is always steadily increasing, is it not a marvellous thing that, out of our own restricted resources, we have succeeded in feeding and maintaining a densely populated nation of 137 people to the square- kilometre? And yet we ourselves will not rest content with what we have done. Our intention is constantly to put new measures into effect in order to secure the prosperity of the German nation. Where we succeed we congratulate ourselves. Where our efforts are not successful we do not allow ourselves to be discouraged. In these cases we always try other ways and means of reaching our goal.

And here I should like to say a word by way of answer to those critics who are always greedily on the look-out for instances in which we fail or partly fail: The man who shoots a great deal will sometimes miss the mark; but those who never shoot will never hit or miss the mark. The problems which we found waiting to be solved were huge problems, thanks to the unique bungling of our predecessors. And these problems were of such a nature that unfortunately we had no examples to guide us in adopting means for their solution. The state of the case today is that many of the measures adopted by us are being taken as examples to be followed in other countries. Almost every step forward that we made was a step into hitherto unexplored territory. We had no other choice. Supposing we had waited until the other States had solved their unemployment problem, so that we might learn from them how to do it, what would have happened? Or ought we to have followed the example of how Russia has fed and maintained fifteen persons per square-kilometre? No, my friends, we took the risk and, I am proud to say, we have won.

During the course of the Congress you will get a more detailed picture of what has been accomplished within the past twelve months. One thing is certain : it is that a more successful effort has never before been made to rescue a nation from the abyss of such an economic, political and moral disaster. And this indicates the nature of the task that we shall have to discharge during the coming twelve months. We shall make a strong effort to bring about a further reduction in the number of our unemployed. We shall strive to maintain the relation of work to wages at the present level and no consideration will make us hesitate in our determination to uphold the interests of the nation against all factors of disorder, no matter where they may show themselves or who they may be.

We shall continue the magnificent social work of our Labour Front. We shall strengthen the Reich in its Army, so as to make it a still safer refuge for European peace and European civilisation. We shall continue all the work that we have begun and we shall enlarge its scope by the addition of new undertakings, with a view to maintaining the economic vitality of Germany and raising the standard of living. But above all we shall consolidate the Movement internally as the source of our power and, in the spirit of the Movement, we shall continue to inculcate in the minds of the German people the ideal of a true community.

We are convinced that this last task is our hardest. For here we have to fight prejudices which have arisen from past experiences. We must struggle against the burden of a bad tradition coming down from former times and we have to contend with the sceptical influence of selfish and small-minded people.

But the favourable results we have already achieved in this direction justify the firm confidence that one day we shall arrive at our definite goal. This however is not an end in itself and we cannot rest idle once we have attained it. We do not want anybody to fall into the mistake of thinking that once a person has become a National Socialist he can rest on his oars. The true National Socialist feels obliged to work unceasingly in the service of the cause. We must teach the coming generation what our inner experiences have been during our struggle in common, so that those people may not easily forget the lesson which the nation has learned from the experience of the past.

And so, my friends, we ought to take this seventh Congress as an opportunity of trying to realise still more profoundly that the mission of our Party is something which must continue to be fulfilled and that in reality there is no such thing as a final accomplishment of it; for that mission commands us to educate our people and therewith to assure the permanent existence and activity of our Party. No matter what may be achieved, the human element stands above every other consideration. Whatever may be our projects or our activities, it is the human element alone that will assure their success and give them their final consecration. As proof of loyal adherence to the National Socialist faith, it is not sufficient to be able to produce the Party passport in attestation of membership. That passport is only the visible and outward sign of an internal faith. This faith imposes on each individual believer the duty of constant self- discipline and unfaltering activity in the service of the cause.

We have assembled together for this Party Congress of 1935 in a time of general unrest. But just as at earlier period of our domestic struggle for power, when heavy storm clouds darkened the political horizon, our ardent faith in the greatness of our mission as National Socialists continued to burn brightly, so once again our faith in that mission gains renewed vigour in face of the international unrest that prevails today.

In those days we always held firm to our faith and hope in the Movement. Today that will not desert us, even though we should be burdened with anxieties and distressed with the insecurity of the times. Rather will our faith continue to be refreshed from those sources which gave us the strength that was necessary for our gigantic struggle. Now that the Bolshevik Jew in Moscow has announced the beginning of a world campaign of destruction we, National Socialists, gather closer together beneath our glorious banner. We unfurl it before us with a sacred vow to fight the old enemy, regardless of life, so that Germany’s future, her honour and her freedom may be saved, protected and secured.

Long live the Reich and the National Socialist Movement!

ART AND POLITICS

Address Delivered

at the Seventh National Socialist Congress, Nuremberg, September 11, 1935

O

N February 27th 1933, when the blaze from the dome of the Reichstag was reflected in a red glow from the sky, it seemed as if Fate had chosen the torch of

the Communist incendiaries to illuminate the grandeur of that historical turning point before the eyes of the nation. The final menace of the Bolshevik revolution hovered like a dark shadow over the Reich. A terrible social and economic catastrophe had brought Germany to the verge of annihilation. The foundations of social life had crumbled. There had been times in which high courage was demanded of us-in the Great War, for instance, and afterwards during our long struggle on behalf of the movement and against the enemies of the nation. But the courage then demanded was not so great: is that which now became necessary when we were faced with the question of taking over the direction of the affairs of the Reich and therewith the responsibility for the existence of the people. During the months that followed it was very difficult to discover and employ such measures as might still avert the final disaster, and doubly difficult to withstand and overthrow the last assault launched by those who wanted to wreck the Nation and the Reich. It was veritably a savage struggle against all those causes and symptoms of German internal disintegration and against our enemies abroad who were hopefully expecting the final debâcle.

At some future date, when it will be possible to view those events in clearer perspective, people will be astonished to find that just at the time the National Socialists and their leaders were fighting a life-or-death battle for the preservation of the nation the first impulse was given for the re-awakening and restoration of artistic vitality in Germany. It was at this same juncture that the congeries of political parties was wiped out, the opposition of the federal states overcome and the sovereignty of the Reich established as sole and exclusive. While the defeated Centre Party and the Marxists were being driven from their final entrenchments, the trades unions abolished, and while the National Socialist thought and ideas were being brought from the world of dream and vision into the world of fact, and our plans were being put into effect one after the other-in the midst of all this we found time to lay the foundations of a new Temple of Art. And so it was that the same revolution that had swept over the State prepared the soil for the growth of a new culture. And certainly not in a negative way. For though there were many grounds on which we might have proceeded against the elements of destruction in our cultural life, as a matter of fact we did not wish to waste time in calling them to account. For we had decided from the start not to be drawn into endless controversy with persons who can be judged by their works and who were either imbeciles or shrewd impostors. Indeed we considered most of the activities of the leaders among these cultural protagonists as criminal. If we had opened a public discussion with such people we should have ended by sending them to some mental asylum or to prison, according as they believed in these fictions of a morbid fancy as real inner experiences or merely offered their deplorable lucubrations as a means of pandering to an equally deplorable tendency of the time.

I need not speak of those Bolshevising Jewish litterateurs who found in such “cultural activity” a practical and effective means of fostering r\ spirit of insecurity and instability among the population of civilised nations. But their existence strengthened our determination to make assured provision for the healthy development of cultural activities in the new State.

To carry out this decision effectively, we resolved that on no account would we allow the dadist or cubist or futurist or intimist or objectivist babblers to take part in this new cultural movement. This was the most practical consequence which resulted from the fact that we had unmasked the so-called culture of the post-war period as really a process of decomposition in the German national being. We had to be intransigent, especially because we felt that our task is not merely to neutralise the effects of that unfortunate period which is now past, but also to fix the main outlines of those cultural features which will be developed during the centuries to come by this first National State that is really German.

It is not a matter for surprise to find that criticisms are advanced against such an undertaking at this particular time. But they are only a repetition of the criticisms that have accompanied every such cultural movement in the past. These objections fall under two general headings. We must ignore, of course, those which are insincerely meant and which come from people who know how effectively we mean to put our cultural policy into practice. Such persons cannot overcome their dislike for the German people and they will do their best to oppose any real progress in Germany. Therefore they try, by way of hostile criticism and sceptical insinuation and open accusation, to place every possible hindrance in the path of our effort. Considering the fundamental and inspiring motives of it, such opposition is in itself an excellent recommendation for our work. Therefore I shall deal here only with the objections which are often put forward by well-meaning people. The first of these objections may be stated thus:-

In view of the arduous nature of the political and economic programme that we have decided to carry out, is it wise at this juncture to bother about problems of art, which may have been of some importance in other centuries and in other circumstances but which are

Just now, isn’t practical work more important than art, the drama, music etc. Excellent though they be in themselves and much to be commended on general grounds, such activities do not minister to lifes’s necessities. Is it right to undertake monumental works of engineering and building, instead of restricting ourselves exclusively to what is practical and absolutely necessary at the moment?

The second line of objection runs thus:-

Can we permit sacrifices to be made in the interests of art at such a time as this when we find ourselves surrounded with poverty, distress, misery and complaining? In the last analysis, isn’t art the luxury of a small minority? What has it to do with the task of supplying bread to the masses?

I think it worth while to examine the grounds of such criticism and answer it. Is it in harmony with the times in which we live, and why should we feel called upon just now, to awaken public interest in questions of art? Would it not be more reasonable to ignore such matters at the present juncture and take them up at some later date when the present economic and political difficulties are over?

In answer to such an attitude the following must be said:-

Art is not one of those human activities that may be laid aside to order and resumed to order. Nor can it be retired on pension, as it were. For either a people is endowed with cultural gifts that are inherent in its very nature or it is not so endowed at all. Therefore such gifts are part of the general racial qualities of a people. But the creative function through which these spiritual gifts or faculties are expressed follows the same law of development and decay that governs all human activity. It would not be possible, for instance, to suspend the study of mathematics and physics in nation without thereby causing a retrogression in the special faculties and aptitudes that are exercised in the pursuit of such studies. And thus in this respect such a nation must necessarily fall behind other nations similarly endowed. For just the same reason, if the cultural activities of a people were suspended for a certain time the necessary result would be a general retrogression throughout the whole cultural sphere; and this would end in a process of internal decay.

Let us take an instance. Opera may be looked upon as one of the most characteristic creations of the neo-classical theatre. Now, if the activities involved in operatic production were to be suspended for a longer or shorter period of time, even though only temporarily, with the intention of restoring opera once again in its old brilliancy-what would be the consequence? There would be a suspension of the training and preparation of the personnel necessary for such productions. But the consequences would not end there. They would extend to the general public: for the receptive faculties of the public, in regard to this particular form of art, have to be developed and trained by the constant production of opera, just as in the case of the performers themselves.

The same holds good for art in general. No era can shelve the duty of cultivating the arts. If it should try to do so it would lose not only the capacity for creative artistic expression but also its powers of comprehending and appreciating such expression; because the creative and receptive faculties are here interdependent. Through the appeal of his work, the creative artist vitalises and ennobles the aesthetic faculties of the nation. And the general feeling for artistic values, thus awakened and developed, becomes a rich spiritual nursing ground for the growth and increase of new creative talent.

But if, by reason of its very nature, such cultural activity cannot be suppressed for a longer or shorter period without causing irremediable damage, such a suppression or neglect would be particularly wicked when the economic and political situation expressly calls for a reinforcement of the moral strength of the nation. It is important that this should be clearly understood. The cultural achievements which mark outstanding periods in human history were always coexistent with a high degree of social development. Whether they belong to the material or spiritual order, it can be said that such works always incorporated the most profound elements of the national being. And never is it more necessary to direct the mind of a people towards the vital and inexhaustible powers of its inner being than when political and social and economic troubles tend to weaken faith in the nobler qualities which the nation incarnates and thereby hinder the fulfilment of its mission. When the poor human soul, oppressed with cares and troubles and inwardly distracted, has no longer a clear and definite belief in the greatness and the future of the nation to which it belongs, that is the time to stimulate its regard for the indisputable evidences of those eternal racial values which cannot be affected in their essence by a temporary phase of political or economic distress. The more the natural and legitimate demands of a nation are ignored or suppressed, or even simply denied, the more important it is that these vital demands should take on the appeal of a higher

and nobler right by giving tangible proof of the great cultural values incorporated in the nation. Such visible demonstration of the higher qualities of a people, as the experience of history proves, will remain for thousands of years as an unquestionable testimony not only to the greatness of a people but also to their moral right to existence.

Even though the last representatives of such a people should submit to the final disgrace of having their mouths closed forever, then the stones themselves will cry out. History pays scarcely any positive regard to a people that has not left its own monument to bear witness to its cultural achievement. On the other hand, those who have destroyed the artistic monuments of a foreign race remain only a subject of regret for the historian.

What would the Egyptians be without their pyramids and their temples and the artistic decorations that surrounded their daily lives? What would the Greeks be without Athens and the Acropolis? What would the Romans be without their mighty buildings and engineering works? What would the German emperors of the middles ages be without their cathedrals and their imperial palaces? And what would the Middle Age itself be without its town halls, and guild halls etc.? What would religion be without its churches? That there was once such a people as the Mayas we should not know at all, or else be unconcerned about them, had they not left for the admiration of our time those mighty ruins of cities that bear witness to the extraordinary epic qualities of that people, such ruins as have arrested the attention of the modern world and are still a fascinating object of study for our scholars.

A people cannot live longer than the works, which are the testimony of its culture.

Therefore if artistic works have more powerful and more durable repercussions than any other human activity, then the cultivation of the arts becomes all the more necessary in an age that is oppressed and distracted by an unfavourable political and economic situation. For Art is more effective than any other means that might be employed for the purpose of bringing home to the consciousness of a people the truth of the fact that their individual and political sufferings are only transitory, whereas the creative powers and therewith the greatness of the nation are everlasting. Art is the great mainstay of a people, because it raises them above the petty cares of the moment and shows them that, after all, their individual woes are not of such great importance. Even if such a nation should go down in defeat, and yet have produced cultural works that are immortal, in the eye of History that nation will have triumphed over its adversary.

The objection that only a small minority of the people understands and takes pleasure in artistic work is based on a false supposition. Any other function in the life of a nation might be chosen and on the same grounds it might be maintained that such a function is unimportant, because the masses of the people have no direct share in it.

Nobody could say that the masses of the people appreciate or partake in the highest results that have been obtained by the sciences of chemistry and physics or indeed in the latest progress made in any other scientific or intellectual pursuit. But I am convinced that the contrary is true of artistic activities. And this is so precisely because Art is the clearest and most immediate reflection of the spiritual life of a people. It exercises the greatest direct and unconscious influence on the masses of the people, always of course on the supposition that it is true and real art, rendering a true picture of the spiritual life and inner powers of the race and not a distortion of these.

This is the true touchstone of the worth or worthlessness of an art. The most decisive condemnation of the whole dadist movement during recent decades is the fact that the great masses of the people have not only turned away from it but that they finally have come to show not the slightest interest in this Judeo-Bolshevik derision of all culture.

The last remnants who more or less believed in these imbecilities were only their own authors. In such circumstances it is true that the proportion of people who interest themselves in art is very small; because it is made up exclusively of mental deficient - that is to say, degenerates-who, thank God, form a very small minority and represent only those elements that are interested in the moral corruption of the nation. We must set aside these efforts to deride all culture and consider them as having no relation to Art. What we can say of Art, in the real sense of the term, is that in its thousand fold manifestations and influences it benefits the nation as a whole by reason of the fact that it gives the people a broad outlook in which they can contemplate and appreciate the nobler virtues of their race and are thus raised above the level of individual interests. And it is the same here as in the case of all the higher human activities. There are many degrees of perfection in the exercise and understanding of such activities.

That is a fortunate nation indeed in which Art has reached such a position that for each individual it stands as the ultimate source of his happiness, almost as a presentiment.

Out of the number of creative artists there are only a few examples where the highest pitch of human achievement has been reached. In like manner the faculty of perfectly comprehending artistic values is not given to all in equal measure. But each person who strives to reach those heights will find an inner and profound satisfaction in each step that he attains.

Therefore if the National Socialist Movement is to have a real revolutionary significance it must strive to give tangible proof of this significance by authentic creative work in the cultural sphere. It must make the people conscious of their collective mission, and of the particular mission of National Socialism, by encouraging and aiding such artistic production as will demonstrate to the people their own cultural resources. The work of the National Socialist Movement and the struggle it has to carry on will become all the more easy in so far as it can effectively impress on the public mind an understanding of the greatness of the aims it has in view. This understanding has always been the result of great cultural achievements, especially in the domain of architecture.

If the nation is to be trained to take pride in itself, the just motives of that pride must be placed before its eyes. The labour and sacrifices which the construction of the Pantheon demanded were the work of one time; but it has been an everlasting source of pride to the Greeks and an object of universal admiration for their contemporaries and for posterity.We also ought to nourish the hope that Providence will grant us great geniuses who may express the soul of our people in everlasting concord of sounds or in stone., We know of course that here as elsewhere the hard saying applies: “Many are called but few are chosen”.

But we are convinced that in the political sphere we have discovered a fitting mode of expression for the nature and will of our people. Therefore we feel that we are capable also of recognising and discovering in the cultural sphere the complementary expression which will be adequate to that nature and that will. We shall discover and encourage artists who will

imprint on the new German State the cultural stamp of the German race, which will be valid for all time.

The second objection I have mentioned is that at a time of material distress we ought to renounce all activity in the sphere of art, because in the last analysis this is only a luxury, suitable indeed to prosperous times but out of place as long as the pressing material wants of the individual are not satisfied. That objection has always been, like poverty itself, the everlasting shadow that has accompanied all artistic creation. For who can sincerely believe that there has ever been a great artistic epoch in which poverty and want did not also exist? Does anybody imagine that when the Egyptians built their pyramids and temples there were not poor people among them? Or in Babylon when its splendid buildings were erected? Has not this objection been advanced against all the greatest cultural creations in history and has it not been heard in all cultural eras? A simple way of answering it is to ask another question: Does anybody think that if the Greeks had not built the Acropolis at all there would have been no poverty or misery in Athens at that time? Or would there have been no human distress in the Middle Ages if they had renounced the idea of building their cathedrals? But let us take an example nearer home. When Ludwig I made Munich a centre of art exactly the same arguments were brought forward against him. Were there no poor and needy people in Bavaria before Ludwig began to carry out his great building plans? Or let us come down to the present time, as it is easier to understand what is before our eyes. National Socialism has made the life of the German people more pleasant in all directions because of the encouragement it has given to cultural activities of the highest kind. Ought we to renounce all that because poverty still exists among us and will exist tomorrow also? Before us and our plans was there no poverty in the country?

On the contrary.

If human existence had not been ennobled by the presence of great works of art it could not have found the road of ascension which led up from the pressing material necessities of primitive existence to a higher level of living. Now, this ascension finally led to a social order which, inasmuch as it brings before the individuals constituting it the importance of the people as a whole, thereby creates a sense of duty towards the community and in that way enhances the life of the individual.

It generally happens that when a nation more or less neglects the cultural side of its existence we have a correspondingly low standard of living and more widespread poverty. Human progress first began and continues to develop through a labour-saving procedure whereby the amount of work hitherto thought indispensable to produce the necessities of life is lessened and a portion of it transferred to domains which are being newly opened and which are accessible only to a small number of people who are materially and intellectually equipped for such new energies.

As the embellishment of life, Art follows the same route. But on that account it cannot by any means be termed a “capitalist” tendency. On the contrary, all the great cultural achievements in the history of mankind have been the product of those forces which spring from the feeling of communion in the social group, so that such works may be said to originate in the community itself. Hence they reflect in their genesis and final form the spiritual life and ideals of the community.

It is therefore no accident that all the great communities in history which were inspired and formed by a definite concept of the world and life, religious or philosophical, have striven to perpetuate themselves through the medium of great cultural works. And in those epochs of religious intensity, where material cares were set aside as far as possible, the human mind achieved the greatest cultural triumphs.

The contrary was the case with Judaism. Infected by the spirit of capitalism through and through, and directing their actions accordingly, the Jews never produced an art that was characteristically their own, and will never create such a thing. Although this people for long periods in its history has had immense individual fortunes at its disposal, it never created an architectural style of its own, nor have the Jews been able to produce a music that reflects their racial characteristics. Even in the building of the Temple at Jerusalem foreign architects had to be employed to help in giving it final shape, just as most of the Jewish synagogues nowadays are the work of German, French and Italian artists. Therefore I am convinced that, after a few years under the National Socialist leadership of State and people, the Germans will produce much more and greater work in the cultural domain than has been accomplished during the recent decades of the Jewish regime. And it must be a source of pride to us that, by some special dispensation of Providence, the greatest architect which Germany has had since the time of Schinkel was able to construct in the new Germany and in the service of the Movement his first and unfortunately his sole monumental masterpiece in stone, as a classic exemplar of a really German sculptural style. But it is easy to find even a more direct refutation of the second objection I have mentioned. In all the great artistic creations of mankind human labour has been employed and salaries paid for it; so that the general amount of work and payment is increased. By putting more work into circulation more money is put into circulation, which creates other employment in other spheres. So that if we consider those cultural works from the purely material viewpoint we find that they always signify a remunerative undertaking which benefits the commonweal. Moreover, they refine and expand human sentiment and in this way they help to elevate the general standard of life. The contemplation of such works makes a people conscious of itself and of its faculties; so that the creative powrers of the individual are thereby awakened and stimulated. But an indispensable condition is required. It is this: If art is to have the effect just mentioned it must be a herald of the sublime and beautiful and the expositor of natural and healthy living.

When it fulfils this condition, then no sacrifice on its behalf can be too great. If it fail to meet this test, then even the smallest expenditure on it is a contribution to evil; for this latter kind of art is not a healthy and constructive factor for the betterment of our existence but rather a mark of degeneration and corruption. What is presented to us under the caption, “Cult of the Primitive”, is not the expression of a naive and untainted primitive consciousness but rather a morbid decadence.

There are people who defend the pictures and sculptures-to mention only an obvious example-of our dadists and cubists and futurists or our self-worshipping impressionists, on the grounds that such effusions are examples of primitive forms of expression. But such people are entirely oblivious of the fact that it is not the purpose of art to be a remembrancer of degenerate symptoms but rather to strive to overcome symptoms of degeneration by directing the imagination to what is eternally good and beautiful. If these botchers who pretend to be artists think that they can stimulate the “primitive” instincts of our people and bring them to expression, they obviously do not realise that our people passed out of the stage represented by these primitive art-barbarians some thousands of years ago. Not only do the people turn away from those noisome productions but they consider the fabricators of them as charlatans

or fools. In the Third Reich we have no idea of allowing such people to batten on the public. An attempt has been made to exculpate them post factum, on the alleged grounds that during a certain period of time it was necessary to pay court to that fashion, because it was so emphatic and dominant. In our eyes such an argument has no validity whatsoever. It only makes the case worse; because it shows an absolute lack of principle in the conduct of such people. Moreover, that kind of explanation is entirely out of place at the present time and it is addressed precisely to the wrong people when it is addressed to us. For if some composer or other today, when reminded of his past aberrations, should put forward the naive excuse that in those days nobody would have paid attention to him if he had not emitted that kind of caterwauling music, we should take the excuse as a condemnation of himself. Our answer is that we were confronted with an exactly similar situation in the political field. It was the same kind of music and the same kind of folly.

Our fellow-feeling and appreciation are reserved exclusively for those who, in this as well as in other spheres, did not pander to the canaille or make obeisance to the Bolshevik madness but opposed them openly and honourably with courage and confidence in their own cause.