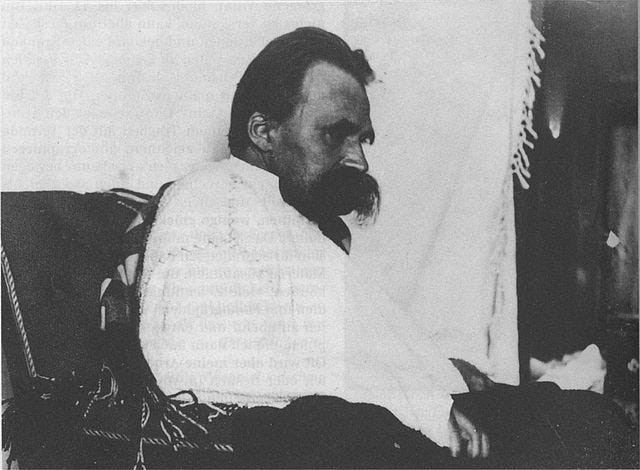

'The Solitude of Nietzsche', by Prof. Dr.Alfred Baeumler

Nimrod de Rosario https://nimrodrosario.blogspot.com/

'The Solitude of Nietzsche', by Prof. Dr.Alfred Baeumler

‘All this, ultimately, belongs to a generation that the two of us will probably not come to know: a generation for which the great troubles for which I have suffered, and by virtue of which, and for the love of which I certainly still live, are destined to become vital and to be transformed into will and action.’ (From a letter from Nietzsche to Overbeck in 1887) [letters are available in (Friedrich Nietzsche, 2005, 2007, 2009a, 2009b, 2011, 2012), some letters in (F. W. Nietzsche, Levy, & Ludovici, 1921), (F. W. Nietzsche & Leidecker, 1959), (Friedrich Nietzsche, 1996)].

The mysterious trail of the one who in 1885 was to write: ‘Today there is no one in Germany who knows what I want or that I want anything [...]’, extends to the heart of the Germany of the first pre-war, increasingly opulent and satisfied. And this, two years later, after having felt multiply the sense of the very deep loneliness that surrounds him, will say, in truth, more for himself than for a professor from Basel named Overbeck: ‘This winter I have made a vast reconnaissance around

European literature [...]; Today's Europe does not have the slightest suspicion of what are the terrible decisions around which my work revolves, and of what is the pivot of the questions to which I refer, it does not even know that a catastrophe is being prepared with me whose name only I who know it will pronounce’.

He will say it to himself, for there are no ears capable of understanding it. It was implausible that he was right, it was plausible instead that he gave voice to a great but unknown psychic predisposition. And precisely the listening was directed to this last eventuality: so did Overbeck and Rohde, whose correspondence on 'Beyond Good and Evil' represents one of the most sensational documents of the nineteenth century. And who could agree that this Europe resplendent with unparalleled prosperity was nearing the end? To warn, to announce the catastrophe, to describe its symptoms and, going further, to invent a ‘countermovement’: all this was Nietzsche's task, all this was what he lived for, since he was able to sustain it. It is almost a scandal that even today someone speaks of Nietzsche as a ‘sufferer’, without referring to his fate, subjective or objective.

What is subjective tends in fact to assume precisely in him, as never in a mortal, a sense of destiny. He does not invent a destiny: he ‘lives’ his own destiny, his destiny. It embodies the turn of times. Nietzsche has no choice, not being able to defect either forward or backward (from the letter to Overbeck of February 3, 1888): a gigantic ‘It’ has taken his seat. There is only one thing left: to say yes, to assume his own destiny: ‘Here I am’ - amor fati.

The needle that indicates magnetic storms oscillates incessantly from one side to the other, always in the direction of the poles. Similarly, the Nietzschean sensibility continually oscillates in this or that direction, but its own sense and consciousness of destiny always remain unchanged. The astonishing consequences of Nietzsche's existence are more easily traced in letters than in works. This existence has shaped a ‘tenacious will’, a will that is misunderstood if thought of as the will to greatness. Nietzsche has ‘wanted’ only one thing: his own destiny. Everything came to him without the need to evoke it, because it was up to him alone to decide. He ‘wanted’, that is, he did not escape what was imposed on him. ‘I am the antithesis of a heroic nature,’ he said of himself in Ecce Homo. ‘No sign of struggle is detectable in my life.’ Nietzsche lives ‘heroically’ and ‘wants’ something, but in him there is no connection between these two concepts, a ‘heroic will.’ The marble bust of Klinger is substantially false. The ‘tenacious will’ is not shown grinding its teeth. Nietzsche redefined the notion of ‘heroic.’ Nietzschean heroism is not that of saints who raise praises to God during martyrdom, nor that of a will that strives for something, nor the heroism of suffering, nor even a heroism of action. For Nietzsche there is only one action that is repeated continuously: his action consists in sustaining his own task and destiny: to be what he is. Its purity is this: to resist to the bitter end.

‘If only I could give you an idea of my sense of loneliness! I have never felt anyone, among the living or the dead, close to me. All this horribly unspeakable: only the daily exercise of this feeling of loneliness and a gradual evolution of it, from the earliest childhood, has made it not yet perish. For the rest, I see before me the task for which I live: a factum of indescribable sadness, but clarified by the awareness that this is greatness, if greatness is suited to the tasks of a mortal.’ (Letter of August 5, 1886).

In 1886 Nietzsche wrote these words to his friend who two and a half years later went to look for him in Turin. For five years now he has lived in the lucidity of which these words of resignation and at the same time of pride are testimony. Based on his statements it is easy to glimpse Nietzsche's ‘megalomania’; we wanted to leave aside everything that infuses meaning and clarity. But what are Nietzsche's conditions in 1881? He has already left behind Aurora, the first systematic attack on morality produced by Christianity. Nietzsche makes a pilgrimage through the heights around Genoa with his gaze back to the future, as no one has yet dared to do. He

feels within himself ‘the summits of reflection and moral action in Europe and of many other things’. (Letter of November 29, 1881). Before the eyes of the solitary appears a distance of historical-universal character, while the present is illuminated with an ineffable light. An era lasting centuries is now at an end. The philosophical thought of the last centuries reveals its authentic late-Gothic face. A man at the height of Columbus lives internally and entirely the end of the Middle Ages! And this man who feels repelled by his own century, projected into the second half of the century that comes after him, such a man, then should not have written: ‘My hour has come’? And this man, looking away from such a distance, should not have written about one of his contemporaries, Richard Wagner: ‘Until that moment I was looking for someone who was superior to me, and knew how to really value me [...]. Now, however, I can no longer even compare myself to him: I fall within a completely different range.’ (Letter of February 3, 1882)?

True, these words sound haughty; but that does not make them fake at all. But if Nietzsche really belonged to another ‘rank’, objectively understood, on the plane of universal history, and if Wagner was already part of a world empire in decline, was not then Nietzsche the nuncio and the representative of a new Kingdom? Reflecting on this latter eventuality can be helpful even for those who are still deaf. Nietzsche saw himself as the antagonist, on the plane of world history, of Wagner, of Schopenhauer, of Bismarck, of the ‘Reich’, of modern Europe. Should not the solution of the tormenting dilemmas of his life and work then consist in the fact that he was indeed such an antagonist?

The contrast with the epoch itself is not based on the fact that Nietzsche, like Wagner, Bismarck, or Goethe, asserted a well-disposed work against the will of contemporaries, against the ‘clumsy world’, so that, in the end, the winner is grateful for this same world. Nietzsche's contrast with his own time has much deeper roots. Nietzsche preceded his people not by one, but by two, if not three generations. Even if he had lived longer, he would never have received the homage of contemporaries. All expressions of his self- consciousness refer to the distance that separates him from his century: Nietzsche does not have a ‘predecessor’. Human greatness remains always the same, regardless of the century in which it manifests itself. However, there is a historical greatness. Nietzsche is one who has a universal vision, persevering with full consciousness in a certain historical position.

The task assumed by Nietzsche demanded of him the sacrifice of all his human sympathies. The ultimate sacrifice demanded was Wagner's detachment. Nietzsche knew well how to separate the human plane from that of history and destiny. He was never obvious: he wrote 'The Antichrist', without ever propagating atheism, he composed 'The Wagner Case', without ever

denying Tribschen's journey. To the harsh criticisms required by the content of the pamphlet are linked the phrases about Wagner present in 'Ecce Homo'. Nietzsche never ignored the greatness of Wagner; but he would have always remained small, if he had not understood to sacrifice the same friendship with Wagner to his recognized opposition of historical-universal dimension.

In January 1887 Nietzsche heard for the first time the orchestral performance of the music of Parsifal, well known to him since the piano reduction (‘Prelude’). In this regard he writes to his sister: ‘I cannot think of it except with deep impression, so much I feel conquered and taken by this music. It is as if, after many years, someone finally spoke to me of the problems that have tormented me for a long time but making me uncomfortable: his is not the answer to which I had been predisposed in some way, but a Christian response, which, in the end, has been the response of the strongest souls that the last two centuries have produced among us’ (Letter of February 22, 1887).

In our view, this is one of the salient passages of the Nietzschean correspondence. Nietzsche, a year before ‘The Wagner Affair’, speaks with such freedom of Parsifal, for which he breaks with Wagner! Never has anyone seen so deeply the fissure between human ‘reality’ and historical ‘reality.’ Nietzsche understands the old Wagner as well as the young Wagner, he certainly loves him no less: it is the powerful force of his own task that distances him from Wagner. What obedience ad purity in the face of his own destiny! And now, however, that singular strabismus: shock and astonishment overwhelm the lone combatant in the sight of the adversary. ‘It is as if, after many years, someone, at last, spoke to me [...]’ For an instant the loner is no longer alone. Listening to the last and most consequential formulation of that to which he does not belong (although he does not deny a dangerous affinity), looking the adversary directly in the eye, he feels himself a real man, while, before the eyes of the friend, he feels the shadow of a shadow...

Rohde and Overbeck were not only opposing natures: they were also distant from each other politically. Rohde was an admirer of Bismarck. Overbeck, on the other hand, had a very lukewarm attitude towards the Reich. However, both relate to Nietzsche without understanding him. And all the more so Overbeck, but only because, unlike Rohde, he was never linked to Nietzsche by a deep bond of friendship knotted in youth.

On June 16, 1878, Rohde, writing to Nietzsche about ‘Human, All Too Human’, without understanding the human and philosophical position assumed by the friend, stigmatizes with provocative frankness his weak scientific scaffolding. And how does Nietzsche respond to him? Praising him: ‘All is well, dear friend: our

friendship does not have such a fragile foundation that it can suddenly be overturned by a book.’

Six years later, on April 10, 1884, Nietzsche sent Overbeck the third part of the Zarathustra with these words: ‘Long live! my old friend Overbeck, here is the first copy of my last Zarathustra: it belongs to you by right! There is an idea, a really great idea, which will certainly keep me alive for a while yet. But this is up to me! The main thing now is that you say it for yourself!’ We do not have the answer from Basel. But Nietzsche's epistolary reply begins: ‘My dear friend Overbeck, deep down it is really beautiful that during these last years we have not moved away, and even, as it seems, neither for the Zarathustra’ (May 2, 1884).

‘Our friendship has not been destroyed even by the Zarathustra’: is a nobler, more delicate, and more respectful reply possible? What should be Nietzsche's state of mind, if in the meantime his memory of having written almost the same thing to Rohde six years earlier had been clouded?

Friends do not understand it: that is why you have to tell them. And this is why Nietzsche continues: ‘In the meantime I intend to assert myself and take advantage of the condition I have conquered for myself: for now, in all probability, I am the most independent man in Europe. My goals and my tasks are vaster than those of any other, and what I call 'great politics' at least gives me a good position from which to look at things present from above.’

Among the letters of the last year of activity, the one addressed by Nietzsche to Overbeck on February 3, 1888, assumes particular prominence. In it Nietzsche, with disturbing precision, indicates the starting point of the path of pain that stands before him. He says he spends days and nights in which he no longer knows how to continue living, seized by a gloomy despair never before experienced. His condition has become unbearable and painful, akin to torture. His last writing (‘The Genealogy of Morals’) gives an account of this in part: ‘(I am) in a state similar to that of a bow tense to the point of breaking, any affection does good, given that it is powerful.’ Extreme affection as a remedy! Who could say it more clearly? But the question remains: ‘What remedy is being talked about here?’

Numerous Nietzschean statements of the last conscious year have, in fact, an echo of megalomania. Here is an example: Nietzsche recommends Gast's musical to Hans von Bülow, who had some time before directed the Hamburg Theatre. But without receiving any response. He therefore sends Bülow a letter, in which he lets him know that the ‘most exalted mind of the age has expressed a wish to him’; adding in his own account to Gast: ‘I am permitted to call myself such’ (From a letter from Nietzsche to Gast of October 14, 1888). Undoubtedly: Nietzsche considers himself a prince

regent, whose wishes are orders. He, with the same ‘arrogance,’ as the Philistines would say, delineates in ‘Ecce Homo’ the external circumstances in which he disposes himself to ‘transvaluation’. In Nietzsche contact with reality thus begins to loosen. The most afflicted year of his life is filled with writings that carry within them the tonality of that ‘African’ serenity, which refers to the ‘noon of music.’ And just as he reaches extreme solitude, Nietzsche's ship moves away from shore. The decisive question sounds like this: 'Is Nietzsche's loneliness a subjective and pathological phenomenon, or a historical reality? Is the Nietzsche of 1888 destined to enter a psychiatric sanatorium or in the history of Europe?'

He who speaks of nothing but himself, is either a monomaniac or a genius of destiny; or truly a great or a megalomaniac: this is the only way worthy of Nietzsche to pose the question.

Wherever the solitary is caught closely linked to his destiny, the symbol emerges in personal terms. Nietzsche's life is full of ‘cases’ he interpreted as symbols. For the understanding of his letters, this moment, so to speak, astrological has a high significance.

In ‘Ecce Homo’ Nietzsche alludes to his own life where he speaks of Stendhal's discovery: ‘Everything that makes an epoch in him came to him by chance and never by order.’ We call ‘casual’ a phenomenon that has no necessary, verifiable, demonstrable relationship with our person (i.e., that is fortuitous). Such an event has, however, for us significance, for the case appears there as destiny. Nietzsche's worldview is fatalistic, not causalist: In ‘The Will to Power’ he combats causalism. When, in the letter addressed to Brandes of November 20, 1888, he speaks of the ‘sense of the case’, Nietzsche thereby defines destiny, and at the same time the true tendency of his own philosophy, which is none other than the discovery of the ‘sense of the case’, or the expression of amor fati.

In 1882 Nietzsche's ‘fatalistic surrender to the gods’ rises to the powerful pathos of waiting that directs each step in a single direction. Their faith remains intact, even after all signs have been revealed to be illusory. ‘In the end, everything comes in due time’ (Letter to Gast, March 5, 1884). Sometimes Nietzsche intentionally plays with symbolic images. And so when he proposes to travel to Corte, in Corsica, to prepare for ‘The Will to Power’, he affirms that, according to his calculations, Corte is the small town in which Napoleon was conceived (Letter to Gast of August 16, 1886). But among the many cases, the most significant is this: the omen constituted by Leipzig, and linked to Goethe, coincides in a singular way with the fact that Nietzsche's remains were buried on August 28, the day of Goethe's birth. As for Wagner, the most fatal presence in Nietzsche's life, the coincidences are densified: at Nietzsche's first arrival at Tribschen, a significant chord resounds; ‘Human, All Too Human’ and Parsifal's poem

‘intersect’; Nietzsche finishes the first part of the Zarathustra just at the ‘sacred hour’ of Wagner's death in Venice.

Amor fati: with this formula, his favorite to indicate his own life, Nietzsche says yes to himself as a symbol. And only those who have understood themselves as a symbol can do so. Nietzsche's life can only become a formidable itinerary of self-knowledge. To grasp himself as a decisive symbol of modern history: this was Nietzsche's task. The most ‘subjectivist’ of all men lives under the most categorical of imperatives. Whoever is willing to ‘transvalue all values’ is a servant of destiny, not a ‘titanic’ aesthete hungry for experiences. Nietzsche became fully aware of this in 1881: ‘I often imagine myself as a scribble that an unknown force has traced on paper to evaluate a new pen’ (Letter to Peter Gast, late August 1881).

In Nietzsche, self-love is more easily glimpsed than the fact that this self-love represents the reverse of his sense of destiny. And we must not forget that in Nietzsche the most horrible declarations of self-love appear when he tries to incite those (and in the first-place friends) who do not suspect in the least with whom they are dealing. Ecce homo must be read as a whole as a single broadside launched by Nietzsche against his own friends. Let us pause to reflect on what Nietzsche means when, bearing in mind Rohde or Overbeck, he writes: ‘Except for my dealings with some artists, and in particular with Richard Wagner, I have never spent a decent hour with Germans.’ In the ‘benevolence’ of the friends he glimpses the worst cynicism, blaming them for never having read his books attentively: ‘And as for my Zarathustra, who of my friends has seen in him anything but an unjustified arrogance and fortunately completely negligible [...]’.

Analogous is the tone of the letter to Overbeck of November 12, 1887, in which Nietzsche, with very provocative accents, speaks of his poetic composition, of the ‘Hymn to Life’, which should be sung in his memory: ‘Let us say a hundred years from now, in case someone realizes what I represent.’ Overbeck seems to have accepted these words without flinching, perhaps because in the same letter Nietzsche introduces the discourse on the appreciation and gratitude he feels for the immutable loyalty of the friend. Whoever knows how to correctly read a letter like this (there are others of the same tenor), perceives in it two voices that contradict each other. Here we can notice a duplicity of meaning that is not at all accidental but constitutes the nature of Nietzsche when writing his own letters. The problem of loneliness, of hiding, of ‘acting out a comedy’, ultimately results in the problem of the communicability of one's own personality. Speaking of a ‘predisposition’ to loneliness and ‘acting out a comedy,’ it is easy to boil down to psychologism. But if you ask yourself what the point of solitude is, you get rid of the problem that has arisen at first sight. Is Nietzsche a lonely stranger, or one who has

been lucky enough not to be able to ‘communicate’ about himself on the historical plane? Is his loneliness the consequence of a natural predisposition, or the expression of how he has come to situate himself between two centuries?

We can pose the question also in this way: does the adversary against whom Nietzsche fights, the nameless chaos that surrounds those who want to become God as man, have a historical name or not? Did Nietzsche truly want to be Dionysus, dying of religious madness (in which case we should take him seriously and venerate him as a God), or is he a historical figure driven into the night of madness by a coincidence of circumstances and events? In no case, however, is the explanation that Nietzsche went mad sufficient. He was crazy, and therefore no longer the ‘Nietzsche’, as happened in January 1889. Only understood as a man is a historical figure, only as a man can he bears a name that is at the same time an idea, but not as insane! As ‘Nietzsche’ he lived as a historical figure until the moment of nervous breakdown. The other considerations do not take any position: they speak of ‘Nietzsche’ and at the same time of a madman, so that the problem arises, also insoluble, of when madness ‘began’. But this is an apparent problem. Is the man we are talking about a madman from the beginning, or the ‘Nietzsche’ who dies spiritually at the beginning of January 1889? If he is a madman, then it makes no sense to speak of ‘Nietzsche’; and let it be done at most out of respect for those whom he has seduced. But if he is ‘Nietzsche’, then it is necessary to confront his work. And yet, it does not serve in this case to ‘partially’ discredit the work by alluding to the megalomania of the Author.

In conclusion: Nietzsche's ‘loneliness’ is a pathological phenomenon or should be considered as a reality of modern history to which attention should at least be paid. The present volume contains the main testimonies of this loneliness, so to speak its procedural records. The process between Nietzsche and the twentieth century, in which such acts play a role, is celebrated among historical greatness, but cannot be decided in the medical field. The medical verdict can never become a historical judgment: it can only take the place of the latter. Conversely, a psychiatrist may, yes, challenge the historian's judgment regarding the person of Nietzsche regarded as a historical figure, but he may neither ‘object’ nor ‘adduce’ evidence.

There can be no moral judgment about Nietzsche's loneliness, let alone a psychological ‘explanation.’ You can only choose between a psychiatric assessment and a historical consideration. But if today it is possible to consider Nietzsche's loneliness in historical terms, this is also a historical fact. Without a precise historical point of view, one cannot grasp Nietzsche's historical solitude.

Nietzsche could always have had around him a small circle of people willing to listen and understand him. What he lacked were like-minded people, who therefore had an idea of the Nietzschean task. ‘It is not that I lack people around me,’ he writes in the letter to Overbeck of October 12, 1886, ‘but what I lack are people who share my same concerns!’ For Nietzsche, the desire for friends is not a whim or even a pretension but is objectively founded. The thinker with his gaze turned to the nihilism of European morality wants people to grasp this event. If, out of benevolence, he is considered half-mad, it is obvious that he expresses this intention.

In the summer of 1885 Nietzsche wrote to Overbeck: ‘Sometimes I feel the lack of a confidential conversation with you and with Jakob Burckhardt, but more to ask you how you manage in this predicament and how you tell each other the news [...]’. After all, he has long known that his desire is an absurdity.

The year 1885 is the year in which Nietzsche becomes fully aware of his irreversible loneliness. He feels at the height of his intellectual strength, having devised a philosophical system, partly conducted: who could therefore dispute his right to speak with full self- awareness? And he behaves in an eminently Nietzschean way: as an angry and excessive man, he allows himself to be carried away by the first impetus of anger, and yet he never says the false. ‘I am very proud if I think anyone can love me. This should obviously presuppose that he knows who I am.’ To indicate the rank that corresponds to him, he quotes Wagner, Schopenhauer, and the founder of Christianity. The juxtaposition is meaningless in itself and can only be understood by considering the recipients, raised in veneration for Wagner and Schopenhauer. But we are not hard to believe that Nietzsche would have named himself along with Wagner, Schopenhauer, and Christ even outside the situation just described...

Interspersed with the most violent vents, we read the phrase that sums it all up: ‘I have never had a friend or a confidant with whom to share my interests, my worries, my indignations: it is a pity that there is no God, for at least One would have come to know them’ (beginning of March 1885). This declares the point of view from which to understand Nietzsche's loneliness: he is as alone as a believer can be with his God, but Nietzsche has no God at all. Therefore, it is a thousand times more alone.

His pride consists in never having erred in his own loneliness, and in this pride lies his own legitimacy to consider himself, and only himself, the turning point of Western history. From this derives, by the way, the grotesque error made by those who claim to be Nietzsche, without ever having known the ‘anguish of isolation’.

Neither God nor friends: the last formula of Nietzschean solitude. Not having a God was necessary for him, not having friends seemed to him at first a fortuitous fact. That he would live without God, Nietzsche knew from youth; and that he had to remain friendless, was for him a bitter experience that for a long time he refused to accept. But the latter cannot be separated from the former: absolute incommunicability does not concern only the extreme conditions of Nietzsche's task; it is an integral part of the task itself.

The passages of Nietzsche's correspondence that make us think of his ‘megalomania’ all bear the same imprint: they claim individuals who are not willing to communicate what they do not know how to capture. They are therefore moments of weakness, of discouragement, during which Nietzsche tries to force the interlocutor to recognize what only he can know.

Nietzsche's loneliness could only grow on Protestant soil. The doctrine of justification by faith constitutes the dogma of the solitude of the soul which presupposes a personal God. And yet, absolute solitude in the face of a personal God is not possible. Man is absolutely alone in sight of his own destiny. The devout man is alone with God, Nietzsche is alone before his fate.

There are two significant passages in which the name of Dante emerges on Nietzsche's lips. In the letter to Overbeck of July 2, 1885, Dante and Spinoza are mentioned as those who best understood their fate of solitude. ‘But their way of thinking, compared to mine, was such as to enable them to endure loneliness; after all, for all those who have had any confidence with a 'God' there has not yet been a loneliness comparable to what I know is mine’.

This epistolary passage sheds light on the certainty with which Nietzsche views his own historical condition: he sees himself as both an end and a beginning. Nietzsche does not present himself as the founder of religions, but, assuming a certain position in Protestant Europe, announces his own word dictated by solitude and destiny. Along with this icy word, which corresponds to Durer’s engraving so beloved by Nietzsche (‘The Knight, Death and the Devil’), another melody now also vibrates. It resonates loudest where Nietzsche speaks of the joy, height, and beauty of his Zarathustra. And when he encounters this tonality, it is as if he wanted to say that neither a Goethe nor a Shakespeare would know how to breathe a moment within the passion and at the height of his Zarathustra; and that Dante, compared to Zarathustra, is only a believer, not one who even believes the truth. Let us isolate for a moment the profound idea that animates this antithesis. Consider the difference of Nietzsche's two references to Dante: the first time he mentions Dante to indicate his own position; the second time he quotes him only to extol Zarathustra. In the first case, this great historical figure sheds light on the difficult and serious struggle waged by Nietzsche as a philosopher against the nihilism of European morality; in the second, Dante's name, along with that of others, becomes a simple means of transforming Zarathustra into a god-like being. When Nietzsche makes Zarathustra say: ‘I draw circles around me and sacred limits, and always less ascend with me to the highest mountains; with ever more sacred mountains I build a mountain’, speaks of loneliness: no one can prevent a poet from ascending ever higher in his feelings and in his consciousness: feelings and conscience do not put up any resistance: one ascends effortlessly in the ether of imagination. Zarathustra moves within this ether to where he presents himself as an Alcyonean poet. Nietzsche's true loneliness is of a completely different nature: it is not poetized but described in its concrete reality; not only experienced in intoxicating moments (and therefore captured in poetic terms), but intensely lived.